So, Daniel, when did you first become aware of London After Midnight?

Daniel: I was about seven years old when I first stumbled into Lon Chaney through my love of all things Universal horror, and just that whole plethora of characters and actors that you just knew by name, but hadn't necessarily seen away from the many still photographs of Frankenstein, Dracula, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. And the Phantom was the one to really spark my interest.

But this was prior to eBay. I couldn't see the film of Lon Chaney's Phantom of the Opera for a year. So, I kind of had the ultimate build to books and documentaries, just teasing me, teasing me all the time. And when I eventually did watch a few documentaries, the one thing that they all had in common was the name Lon Chaney.

I just thought I need to learn more about this character Lon Chaney, because he just found someone of superhuman proportions just who have done all of these crazy diverse characters. And, that's where London After Midnight eventually peeked out at me and, occupied a separate interest as all the Chaney characterizations do.

So how did you get into the Universal films? Were you watching them on VHS? Were they on tv? Did the DVDs happen by then?

Daniel: I was still in the VHS days. My dad is a real big fan of all this as well. So he first saw Bela Lugosi's Dracula, on TV when he was a kid. And prior to me being born he had amassed a huge VHS collection and a lot of those had Boris Karloff, Bela Lugosi, Henry Hull, Claude Rains, Vincent Price, what have you.

And a lot of them were dedicated to Universal horrors. And as a young curious kid, my eyes eventually crossed these beautiful cases and I really wanted to watch them. I think my first one I ever watched was The Mummy's Tomb or Curse of the Mummy. And it's just grown ever since, really.

You're starting at the lesser end of the Universal monsters. It's like someone's starting the Marx Brothers at The Big Store and going, "oh, these are great. I wonder if there's anything better?"

Daniel: I really had no immediate go-to reference for London after Midnight, away from one or two images in a book. Really clearly they were very impactful images of Chaney, skulking around the old haunted mansion with Edna Tichenor by his side with the lantern, the eyes, the teeth, the cloak, the top hat, the webs, everything. Pretty much everything that embodies a good atmospheric horror movie, but obviously we couldn't see it.

So that is all its fangs had deepened itself into my bloodstream at that point, just like, why is it lost? Why can't I see it? And again, the term lost film was an alien concept to me at a young age. I've always been a very curious child. Anything that I don't know or understand that much, even things I do understand that well, I always have to try to find out more, 'cause I just can't accept that it's like a bookend process. It begins and then it ends.

And that was the thing with London after Midnight. Everything I found in books or in little interviews, they were just all a bit too brief. And I just thought there has to be a deeper history here, as there are with many of the greatest movies of all time. But same with the movies that are more obscure. There is a full history there somewhere because, 'cause a film takes months to a year to complete.

It was definitely a good challenge for me. When we first had our first home computer, it was one of those very few early subjects I was typing in like crazy to try to find out everything that I could. And, that all incubated in my little filing cabinet, which I was able to call upon years later.

Some things which were redundant, some things which I had the only links to that I had printed off in advance quite, sensibly so, but then there were certain things that just had lots of question marks to me. Like, what year did the film perish? How did it perish? The people who saw the film originally?

And unlike a lot of Chaney films, which have been covered in immense detail, London after Midnight, considering it's the most famous of all lost films, still for me, had major holes in it that I just, really wanted to know the answers to.

A lot of those answers, eventually, I found, even people who knew and institutions that knew information to key events like famous MGM Fire, they were hard pressed to connect anything up, in regards to the film. It was like a jigsaw puzzle. I had all these amazing facts. However, none of them kind of made sense with each other.

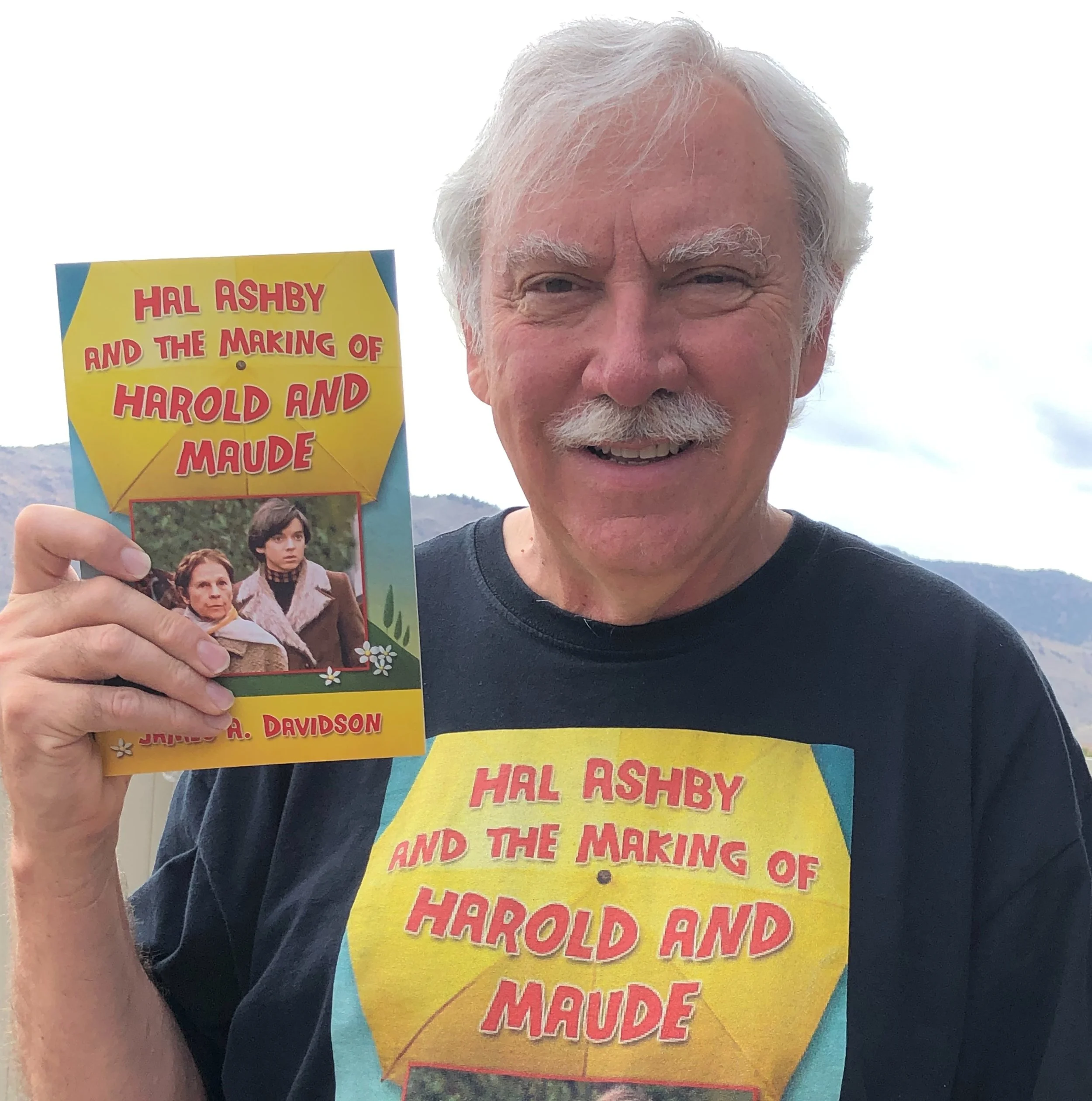

My favorite thing is researching and finding the outcomes to these things. So that's originally what spiraled me into the storm of crafting this, initial dissertation that I set myself, which eventually became so large. I had to do it as a book despite, I'd always wanted to do a book as a kid.

When you see people that you idolize for some reason, you just want to write a book on them. Despite, there had been several books on Lon Chaney. But I just always knew from my childhood that I always wanted to contribute a printed volume either on Chaney or a particular film, and London after Midnight seemed to present the opportunity to me.

I really just didn't want it to be a rehash of everything that we had seen before or read before in other accounts or in the Famous Monsters of Filmland Magazine, but just with a new cover. So, I thought I would only do a book if I could really contribute a fresh new perspective on the subject, which I hope hopefully did.

Oh, you absolutely did. And this is an exhaustive book and a little exhausting. There's a ton of stuff in here. You mentioned Famous Monster of the Filmland, which is where I first saw that image. There's at least one cover of the magazine that used that image. And Forrest Ackerman had some good photos and would use them whenever he could and also would compare them to Mark the Vampire, the remake, partially because I think Carol Borland was still alive and he could interview her. And he talked about that remake quite a bit.

But that iconic image that he put on the cover and whenever he could in the magazine--in my mind when you think of Lon Chaney, there's three images that come to mind: Phantom of the Opera, Quasimoto, and this one. And I think this one, the Man in the Beaver hat probably is the most iconic of his makeups, because, 'cause it is, it's somehow it got adopted into the culture as this is what you go to when it's a creepy guy walking around. And that's the one that everyone remembers. Do you have any idea, specifically what his process was for making that look, because it, it is I think ultimately a fairly simple design. It's just really clever.

Daniel: Yes, it probably does fall into the category of his more simplistic makeups. But, again, Chaney did a lot of things simplistic-- today --were never seen back then in say, 1927. Particularly in the Phantom of the Opera's case in 1925, in which a lot of that makeup today would be done through CG, in terms of trying to eliminate the nose or to make your lips move to express dialogue.

Chaney was very fortunate to have lived in the pantomime era, where he didn't have to rely on how his voice would sound, trying to talk through those dentures, in which case the makeup would probably have to have been more tamed to allow audio recorded dialogue to properly come through.

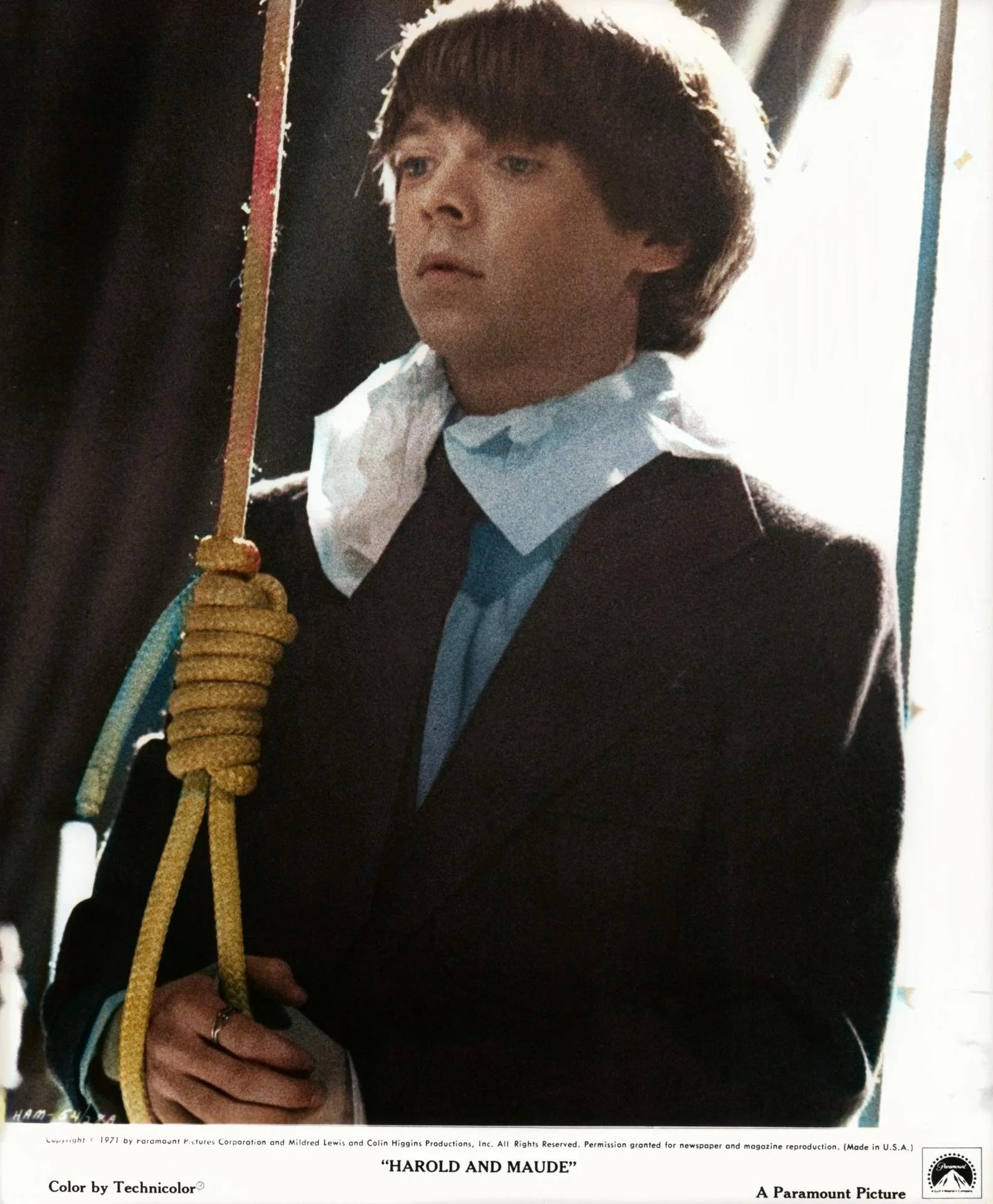

But with regards to the beaver hat makeup, he had thin wires that fitted around his eyes to give it a more hypnotic stare. The teeth, which he had constructed by a personal dentist, eventually had a wire attached to the very top that held the corners of his mouth, opening to a nice curved, fixated, almost joker like grin.

You can imagine with the monocles around his eyes, he was thankful there probably wasn't that much wind on a closed set, because he probably couldn't have closed his eyes that many times. But a lot of these things become spoken about and detailed over time with mythic status. That he had to have his eyes operated on to achieve the constant widening of his eyelids. Or the teeth -- he could only wear the teeth for certain periods of time before accidentally biting his tongue or his lips, et cetera.

But Chaney certainly wasn't a sadist, with himself, with his makeups. He was very professional. Although he did go through undoubtedly a lot of discomfort, especially probably the most, explicit case would be for the Hunchback of Notre Dame, in which his whole body is crooked down into a stooped position.

But, with London After Midnight, I do highly suspect that the inspiration for that makeup in general came from the Dracula novel. And because MGM had not acquired the rights to the Dracula novel, unlike how Universal acquired the rights of the Hunchback or, more importantly, Phantom of the Opera, by which point Gaston Leroux was still alive.

It was just a loose adaptation of Dracula. But nevertheless, when you read the description of Dracula in Bram Stoker's novel, he does bear a similarity to Chaney's vampire, in which it's the long hair, a mouth full of sharp teeth, a ghastly pale palor and just dressed all in black and carries around a lantern.

Whereas Bela Lugosi takes extraordinary leaps and turns away from the Stoker novel. But it must have definitely had an impact at the time, enough for MGM to over-market the image of Chaney's vampire, which only appears in the film for probably just under four minutes, compared to his detective disguise, which is the real main character of the film.

Although the thing we all wanna see is Cheney moving about as the vampire and what facial expressions he pulled. It's just something that we just want to see because it's Lon Chaney.

Right. And it makes you wonder if he had lived and had gotten to play Dracula, he kind of boxed himself into a corner, then if he'd already used the look from the book, you wonder what he would've come up with, if Lugosi hadn't done it, and if Chaney had had been our first Dracula.

The other thing that I think of is here's a guy who -- take Hunchback or Phantom or even this thing -- whatever process he went through to put that makeup on, you know, was hours of work, I'm sure. Hunchback several hours of work to get to that, that he did himself, and then they'd film all day.

So, on top of, I mean, I just think that that's like, wow, when you think about today where somebody might go into a makeup chair and have two or three people working on them to get the look they want. Even if it took a few hours, that person is just sitting there getting the makeup done. He's doing all of this, and then turns in a full day, uh, in front of the cameras, which to me is like, wow, that's incredible.

Daniel: Definitely, it's like two jobs in one. I imagine for an actor it must be really grueling in adapting to a makeup, especially if it's a heavy makeup where it covers the whole of your head or crushes down your nose, changes your lips, the fumes of chemicals going into your eyes.

But then by the end of it, I imagine you are quite exhausted from just your head adapting to that. But then you have to go out and act as well. With Chaney, I suppose he could be more of a perfectionist than take as much time as he wanted within reason. And then once he came to the grueling end of it all, he's actually gotta go out and act countless takes. Probably repair a lot of the makeup as well after, after a couple of takes, certainly with things like the Hunchback or the Phantom of the Opera.

And, you know, it's not only is he doing the makeup and acting, but in, you know, not so much in London After Midnight, but in Phantom of the Opera, he is quite athletic. When the phantom moves, he really moves. He's not stooped. He's got a lot of energy to him and he's got a makeup on that, unlike the Quasimoto makeup, what he's attempting to do with the phantom is, reductive. He's trying to take things away from his face.

And he's using all the tricks he knows and lighting to make that happen, but that means he's gotta hit particular marks for the light to hit it just right. And for you to see that his face is as, you know, skull-like as he made it. When you see him, you know, in London After Midnight as the professor inspector character, he has got a normal full man's face. It's a real face. Much like his son, he had a kind of a full face and what he was able to do with a phantom and take all that away, and be as physical as he was, is just phenomenal. I mean, he was a really, besides the makeup, he was a really good actor.

Daniel: Oh, definitely.

I wonder if he was the makeup artist, but not the actor and he did exactly the same makeup on somebody else. And so we had the same image. If those things would've resonated with us the way they do today. I think it had everything to do with who he was and his abilities in addition to the incredible makeup. He was just a tremendous performer.

Daniel: Absolutely. He was a true multitasker. In his early days of theater, he was not only an actor, but he was a choreographer. He had a lot of jobs behind the scenes as well. Even when he had become a star in his own time, he would still help actors find the character within them. like Norma Sheera, et cetera. People who were kind of new to the movie making scene and the directors didn't really have that much patience with young actors or actresses.

Whereas Chaney, because of his clout in the industry, no one really interfered with Chaney's authority on set. But he would really help actors find the character, find the emotion, 'cause it was just all about how well you translate it over for the audience, as opposed to the actor feeling a certain way that convinces themselves that they're the character. Chaney always tried to get the emotions across to the audience. Patsy Ruth Miller, who played Esemerelda in in the Hunchback, said that Chaney directed the film more than the director actually did.

The director was actually even suggested by Chaney. So, Chaney really had his hands everywhere in the making of a film. And Patsy Ruth Miller said the thing that she learned from him was that it's the actress's job to make the audience feel how the character's meant to be feeling, and not necessarily the actor to feel what they should be feeling based on the script and the settings and everything.

So I think, that's why Chaney in particular stands out, among all of the actors of his time.

I think he would've transitioned really well into sound. I think, he had everything necessary to make that transition. There's one sound picture with him in it, isn't there, doesn't he? Doesn't he play a ventriloquist?

Daniel: Yes, it was a remake of The Unholy Three that he had made in 1925 as Echo the ventriloquist, and the gangster. And yes, by the time MGM had decided to pursue talkies -- also, funny enough, they were one of the last studios to transition to, just because they were the most, one, probably the most dominant studio in all of Hollywood, that they didn't feel the pressure to compete with the burgeoning talkie revolution.

So they could afford to take their time, they could release a talkie, but then they could release several silent films and the revenue would still be amazing for the studio. Whereas other studios probably had to conform really quick just because they didn't have the star system, that MGM shamelessly flaunted.

And several Chaney films had been transitioned to sound at this point with or without Chaney. But for Chaney himself, because he himself was the special effect, it was guaranteed to be a winner even if it had been an original story that isn't as remembered today strictly because people get to hear the thing that's been denied them for all this time, which is Chaney's voice.

And he would've transitioned very easily to talkies is because he had a very rich, deep voice, which, coming from theater, he had to have had, in terms of doing dialogue. He wasn't someone like a lot of younger actors who had started out predominantly in feature films who could only pantomime lines. Chaney actually knew how to deliver dialogue, so it did feel natural and it didn't feel read off the page.

And he does about five voices in The Unholy Three. So MGM was truly trying to market, his voice for everything that they could. As Mrs. O'Grady, his natural voice, he imitates a parrot and a girl. And yeah, he really would've flourished in the sound era.

Any surprises, as it sounds like you were researching this for virtually your whole life, but were there any surprises that you came across, as you really dug in about the film?

Daniel: With regards to London after Midnight, the main surprise was undoubtedly the -- probably the star chapter of the whole thing -- which is the nitrate frames from an actual destroyed print of the film itself, which sounds crazy to even being able to say it. But, yeah the nitrate frames themselves presented a quandary of questions that just sent me into a whole nother research mode trying to find out where these impossible images came from, who they belonged to, why they even existed, why they specifically existed.

Because, looking for something that, you know, you are told doesn't exist. And then to find it, you kind of think someone is watching over you, planting this stuff as though it's the ultimate tease. To find a foreign movie poster for London After Midnight would be one thing, but to find actual pieces of the lost film itself. It was certainly the most out of body experience I've ever had. Just to find something that I set out to find, but then you find it and you still can't believe that you've actually found it.

How did you find it?

Daniel: I had connections with a few foreign archives who would befriend me and took to my enthusiasm with the silent era, and specifically Chaney and all the stars connected to Chaney films.

And, quite early on I was told that there were a few photo albums that had various snippets of silent films from Chaney. They didn't really go into what titles these were, 'cause they were just all a jumble. All I knew is that they came from (garbled) widow. And he had acquired prints of the whole films from various, I suppose, junk stores in Spain.

But not being a projectionist, he just purely took them at the face value that he just taken the images and snipping them up and putting them in photo albums, like how you would just do with photographs. And then the rest of the material was sadly discarded by fire. So, all we were left with were these snipped relics, survivors almost to several Chaney lost films. Some of them not lost, but there were films like The Phantom of the Opera in there, the Hunchback of Notre Dame, Mockery, The Unknown.

But then there were several lost films such as London After Midnight, the Big City, Thunder. And All the Brothers were Valiant, which are mainly other than Thunder are all totally complete lost films.

So, to find this little treasure trove, it was just finding out what the images meant and connecting them up, trying to put them in some sort of chronological scholarly order. Grueling, but it was very fun at the same time. And because I had identified myself with all of these surviving production stills from the film -- a lot of them, which formed the basis of the 2002 reconstruction by Turner Classic Movies -- it didn't take me too long to identify what scenes these surviving nitrate frames were from.

But there were several frames which had sets that I recognized and costumes that I recognized, but in the photographic stills, they don't occupy the same space at the same time. So, it's like the two separate elements had crossed over. So that left me with a scholarly, question of what I was looking at.

I was able to go back and, sort of rectify certain wrongs that have been accepted throughout the sixties as being the original, say, opening to London after Midnight. So I've, been able to disprove a few things that have made the film, I suppose, a bit more puzzling to audiences. Some audiences didn't really get what the plot was to begin with. So, it was nice to actually put a bit more order to the madness finally.

At what point did you come across the original treatment and the script?

Daniel: The treatment and the script, they came from a private collector who had bought them at auction a number of years ago who I was able to thankfully contact, and they still had the two documents in question. I had learned through Philip J Riley's previous books on London after Midnight that he had the two latter drafts of the script, the second edition and the third draft edition.

And, again, the question of why and where. I just always wondered where that first draft of the script was, hoping it would contain new scenes, and open new questions for me and to study. And once I've managed to find those two documents, they did present a lot of new, perspectives and material that added to the fuller plot of the original hypnotist scenario, as opposed to the shortened, time efficient London After Midnight film that was ultimately delivered to audiences. So again, it helped to put a little bit more order to the madness.

You found an actual piece of the film that you were able to, somebody got images from it? And then you found the scripts? But the images are terrific and they're all in your book. They came from what exactly?

Daniel: The just below 20 images of the film came from originally a distribution print, a Spanish distribution print, from about 1928. Originally, they were on 35 millimeter indicating that they were from the studio and as is with a lot of silent films that have been found in foreign archives.

Normally when a film is done with its distribution, it would have to be returned to the original studio to be destroyed, except for the original negative and a studio print, because there is no reason why a studio would need to keep the thousands of prints when they have the pristine copy in their vault.

But, in a lot of smaller theater cases, in order to save money on the postage of the shipping, they would just basically declare that they had destroyed the film on the studio's behalf. There was no record system with this stuff and that's how a lot of these films ended up in the basements of old theaters, which are eventually when they closed, the assets were sold off to collectors or traveling showmen. And eventually these films found their ways into archives or again, private collections. Some of which people know what they have.

A lot of times they don't know what they have because they're more obsessed with, naturally, more dedicated to preserving the films of their own culture that was shown at the time, as opposed to a foreign American title, which they probably assume they already have a copy of. But it's how a lot of these films get found.

And, with the London After Midnight, example, there were the images that I found spanned the entire seven reels, because they came from different points in the film. It wasn't a single strip of film, of a particular scene. Having thankfully the main source that we have for London After Midnight is the cutting continuity, which is the actual film edited down shot for shot, length for length.

And it describes, briefly, although descriptive enough, what is actually in each and every single shot of the film. And comparing the single frame images from the film with this document, I was able to identify at what point these frames came from during the film, which again spanned the entire seven reels, indicating that a complete seven reel version of the film had gotten out under the studio system at one point.

As is the case, I'm assuming, 'cause these came from the same collection, I'm assuming it was the same with the other lost Chaney films that again, sadly only survive in snippet form.

It's like somebody was a collector and his wife said, "well, we don't have room for all this. Just take the frames you like and we'll get rid of the rest of it."

So, you mentioned in passing the 2002 reconstruction that Turner Classic Movies did using the existing stills. I don't know if they were working from any of the scripts or not. That was the version I originally saw when I was working on writing, those portions of The Misers Dream that mentioned London After Midnight.

Based on what you know now, how close is that reconstruction and where do you think they got it right and where'd they get it wrong?

Daniel: The 2002, reconstruction, while a very commendable production, it does stray from the original edited film script. Again, the problem that they clearly faced on that production is that there were not enough photographed scenes to convey all the photographed scenes from the film. So what they eventually fell into the trap of doing was having to reuse the same photograph to sometimes convey two separate scenes, sometimes flipping the image to appear on the opposite side of the camera. And, because of the certain lack of stills in certain scenes cases, they had to rewrite them.

And sometimes a visual scene had to have been replaced with an inter-title card, merely describing what had happened or describing a certain period in time, as opposed to showing a photograph of what we're meant to be seeing as opposed to just reading. So, they did the best with what they had.

But since then, there have been several more images crop up in private collections or in the archives. So, unless a version of the film gets found, it's certainly an endeavor that could be revisited, I think, and either do a new visual reconstruction of sort, or attempt some sort remake of the film even.

They certainly have the materials to do that. I've got an odd question. There's one famous image, a still image from the film, showing Chaney as Professor Burke, and he is reaching out to the man in the beaver hat whose back is to us. Is that a promo photo? Spoiler alert, Burke is playing the vampire in the movie. He admits that that's him. So, he never would've met the character. What is the story behind that photo?

Daniel: There are actually three photographs depicting that, those characters that you described. There are the two photographs which show Chaney in the Balfor mansion seemingly directing a cloaked, top hatted figure with long hair, with its back towards us. And then there is another photograph of Chaney in the man in the beaver hat disguise with a seemingly twin right beside him outside of a door.

Basically the scenes in the film in which Chaney appear to the Hamlin residents, the people who are being preyed upon by the alleged vampires, the scenes where Chaney and the vampire need to coexist in the same space or either appear to be in the same vicinity to affect other characters while at the same time interrogating others, Chaney's character of Burke employs a series of assistants to either dress up as vampires or at certain times dress up as his version of the vampire to parade around and pretend that they are the man in the beaver hat. Those particular shots, though, the vampire was always, photographed from behind rather than the front.

The very famous scene, which was the scene that got first got me interested in London After Midnight, in which the maidm played by Polly Moran is in the chair shrieking at Chaney's winged self, hovering over her. It was unfortunate to me to realize that that was actually a flashback scene told from the maid's perspective.

And by the end of the film, the maid is revealed to be an informant of Burke, a secret detective also. So, it's really a strong suspension of disbelief has to be employed because the whole scene of Chaney chasing the maid through the house and appearing under the door, that was clearly just the MGMs marketing at work just to show Chaney off in a bizarre makeup with a fantastic costume.

Whereas he is predominantly the detective and the scenes where he's not needed to hypnotize a character in the full vampire makeup, he just employs an assistant who parades around in the house as him, all the times with his back turned so that the audience can't latch on as to who the character actually is, 'cause it must have posed quite a fun confusion that how can Chaney be a detective in this room where the maid has just ran from the Vampire, which is also Chaney?

Yeah, and it doesn't help that the plot is fairly convoluted anyway, and then you add that layer. So, do you think we'll ever see a copy of it? Do you think it's in a basement somewhere?

Daniel: I've always personally believed that the film does exist. Not personally out of just an unfounded fanboy wish, but just based on the evidence and examples of other films that have been found throughout time. Metropolis being probably the most prominent case.

But, at one point there was nothing on London After Midnight and now there is just short of 20 frames for the film. So, if that can exist currently now in the year 2023, what makes us think that more footage can't be found by, say, 2030? I think with fans, there's such a high expectation that if it's not found in their own lifetime or in their own convenience space of time, it must not exist.

There's still a lot of silent lost treasures that just have not been found at all that do exist though. So, with London After Midnight, from a purely realistic standpoint, I've always theorized myself that the film probably does exist in an archive somewhere, but it would probably be a very abridged, foreign condensed version, as opposed to a pristine 35-millimeter print that someone had ripped to safety stock because they knew in the future the film would become the most coveted of all lost films.

So, I do believe it does exist. The whole theory of it existing in a private collection and someone's waiting to claim the newfound copyright on it, I think after December of last year, I think it's finally put that theory to rest. I don't think a collector consciously knows they have a copy of it. So, I think it's lost until found personally, but probably within an archive.

Lost until found. That's a great title for a book. I like that a lot. What do you think of the remake, Mark of the Vampire and in your opinion, what does it tell us about, London After Midnight?

Daniel: Well, Mark of the Vampire came about again, part of the Sound Revolution. It was one of those because it was Chaney and Todd Browning's most successful film for the studio. And Browning was currently, being held on a tight leash by MGM because of his shocking disaster film Freaks, I suppose they were a little bit nervous about giving him the reign to do what he wanted again.

So, looking through their backlog of smash silent hits, London After Midnight seemed the most logical choice to remake, just simply because it was their most, successful collaboration. Had it have been The Unholy Three, I'm sure? Oh no, we already had The Unholy Three, but had it have been another Browning Chaney collaboration, it might have been The Unknown, otherwise. So, I suppose that's why London After Midnight was selected and eventually turned into Mark of the Vampire.

The story does not stray too much from London After Midnight, although they seem to complicate it a little bit more by taking the Burke vampire character and turning it this time into three characters played by three different actors, all of which happened to be in cahoots with one another in trying to solve an old murder mystery.

It's very atmospherical. You can definitely tell it's got Todd Browning signature on it. It's more pondering with this one why they just did not opt to make a legit, supernatural film, rather than go in the pseudo vampire arena that they pursued in 1927. Where audiences had by now become accustomed to the supernatural with Dracula and Frankenstein in 1931, which no longer relied on a detective trying to find out a certain mystery and has to disguise themselves as a monster.

The monster was actually now a real thing in the movies. So I think if Bela Lugosi had been given the chance to have played a real Count Mora as a real vampire, I think it would've been slightly better received as opposed to a dated approach that was clearly now not the fashionable thing to do.

I suppose again, because Browning was treading a very thin line with MGM, I suppose he couldn't really stray too far from the original source material. But I find it a very atmospherical film, although I think the story works better as a silent film than it does as a sound film, because there's a lot of silent scenes in that film, away from owls, hooting and armadillos scurrying about and winds.

But I do think, based on things like The Cat and The Canary from 1927 and The Last Warning, I just think that detective sleuth with horror overtones serves better to the silent world than it does the sound world away from the legit, supernatural.

So, if Chaney hadn't died, do you think he would have played Dracula? Do you think he would've been in Freaks? Would Freaks have been more normalized because it had a big name in it like that?

Daniel: It would've been interesting if Chaney had played in Freaks. I think because Todd Browning used the kinds of individuals that he used for Freaks, maybe Chaney would've, for a change, had been the most outta place.

I do think he might have played Dracula. I think Universal would've had a hell of a time trying to get him over because he had just signed a new contract with MGM, whereas Todd Browning had transferred over to Universal by 1930 and really wanted to make Dracula for many years and probably discussed it with Chaney as far back as 1920.

But certainly MGM would not have permitted Chaney to have gone over to Universal, even for a temporary period, without probably demanding a large piece of the action, in a financial sense, because Universal had acquired the rights to Dracula at this point. And, based on the stage play that had, come out on Broadway, it was probably assured that it was going to be a giant moneymaker, based on the success of the Dracula play.

But because of Chaney's, status as a, I suppose retrospectively now, as a horror actor, he was probably the first person to be considered for that role by Carl Laemmle, senior and Junior for that matter. And Chaney gone by 1930, it did pose a puzzle as to who could take over these kinds of roles.

Chaney was probably the only one to really successfully do it and make the monster an actual box office ingredient more than any other actor at that time, as he did with. Phantom, Blind Bargain and London After Midnight. So, I think to have pursued Chaney for a legit, supernatural film would've had enormous possibilities for Browning and Chaney himself.

You can kind of see a trend, a trilogy forming, with Browning, from London After Midnight, in which he incorporates things he used in Dracula in London After Midnight. So, he kind of had this imagery quite early on. So, to go from – despite it's not in that order -- but to have London After Midnight, Mark of the Vampire, and he also did Dracula, he clearly was obsessed with the story.

And I think Chaney was probably the, best actor for someone like Browning who complimented his way of thinking and approach to things like silence. As opposed to needing dialogue all the time, loud commotions. So, I think they dovetailed each other quite well, and that's why their ten year director actor relationship was as groundbreaking as it was.

If the film does surface, if we find the film, what do you think people, how are they gonna react to the movie when they see it? What do you think? What's gonna be the reaction if it does surface?

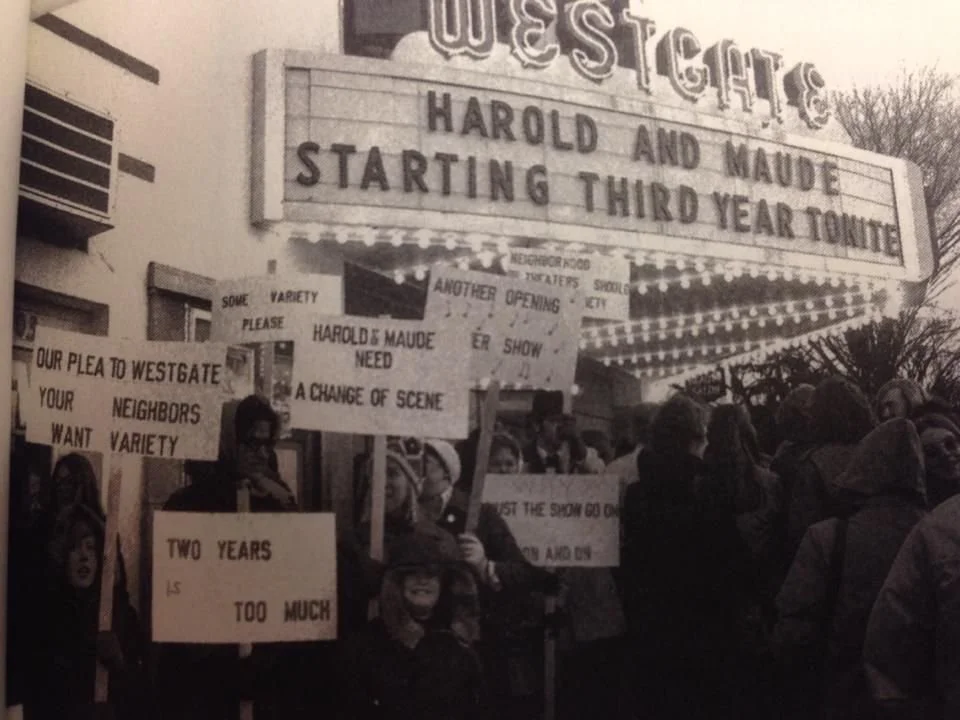

Daniel: Well, the lure of London After Midnight, the power in the film is its lost status rather than its widespread availability. I think it could never live up to the expectation that we've built up in our heads over the past 40 to 60 years. It was truly people, fans like Forrest J Ackerman that introduced and reignited the interest in Chaney's career by the late fifties and 1960s. That's when London After Midnight started to make the rounds in rumor, the rumors of a potential print existing, despite the film had not long been destroyed at that point. So, it was always a big mystery. There were always people who wanted to see the film, but with no access to home video, or et cetera, the only way you could probably see the film would've been at the studio who held everything.

And, by the time the TV was coming out, a lot of silent films didn't make it to TV. So again, it has just germinated in people's heads probably in a better form than what they actually remembered. But, the true reality of London After Midnight is one more closer to the ground than it is in it's people are probably expecting to see something very supernatural on par with Dracula, whereas it's more so a Sherlock Holmes story with mild horrorish overtones to it that you can kind of see better examples of later on in Dracula in 1930 and in Mark of the Vampire.

It's a film purely, I think for Lon Chaney fans. For myself, having read everything I can on the film, everything I've seen on the film, I personally love silent, detective stories, all with a touch of horror. So, I personally would know what I am going in to see. I'm not going in to see Chaney battling a Van Helsing like figure and turn to dust at the very end or turning to a bat. I'm going to see a detective melodrama that happens to have what looks like a vampire.

So, it certainly couldn't live up to the expectations in people's minds and it's probably the only film to have had the greatest cheapest, marketing in history, I would think. It's one of those films, if it was discovered, you really would not have to do much marketing to promote it.

It's one of those that in every fanzine, magazine, documentary referenced in pop. It has really marketed itself into becoming what I always call the mascot of the genre. There are other more important lost films that have been lost to us. The main one again, which has been found in its more complete form, was Metropolis, which is a better movie.

But unlike Metropolis, London After Midnight has a lot more famous ingredients to it. It has a very famous director. It has a very famous actor whose process was legendary even during then. And it's actually the only film in which he actually has his make-up case make a cameo appearance by the very end.

And it goes on the thing that everyone in every culture loves, which is the vampirism, the dark tales and folklore. So, when you say it, it just gets your imagination going. Whereas I think if you are watching it, it's probably you'll be looking over the projector to see if something even better is going to happen.

The film had its mixed reactions when it originally came out. People liked it because it gave them that cheap thrill of being a very atmospherical, haunted house with the creepy figures of Chaney walking across those dusty hallways. But then the more important story is a murder mystery.

It's not Dracula, but it has its own things going for it. I always kind of harken it back to the search for the Lochness Monster or Bigfoot. It has more power in your mind than it does in an aquarium or in a zoo. Hearing someone say that they think they saw something moving around in Lochness, but there's no photographic evidence, you just have the oral story, that is much more tangible in a way than actually seeing it in an aquarium where you can take it for granted.

And it's the same with London After Midnight, and I think that's why a lot of hoaxster and pranksters tend to say that they have seen London After Midnight more than any other lost film.

For a film that I would say the majority of the world does not have any frame of reference, that image is iconic in a way that has been, I mean, it at first glance could be Jack the Ripper. Once I locked in on that image, then I started to think, oh, the ghosts in Disney's Haunted Mansion, there's a couple of ghosts that have elements of that. I mean, it was so perfectly done, even though we don't, I bet you nine out ten people don't know the title London After Midnight, but I bet you seven outta ten people know this image.

Daniel: Definitely, it has certainly made its mark on pop culture, again, I think because I think it's such a beautiful, simplistic design. Everything from the simplistically [garbled] to the bulging eyes and the very nice top hat as well, which is in itself today considered a very odd accessory for a grotesque, vampire character.

But it's one of those things that has really carried over. It's influenced what the movies and artists. It was one of the influences for the Babadook creation for that particular monster. It was an influence on the Black Phone. It's just a perfect frame of reference for movie makers and sculptors and artists to keep taking from.

Yep. It's, it'll live long beyond us. Daniel, one last question. I read somewhere or heard somewhere. You're next gonna tackle James Whale, is that correct?

Daniel: James Whale is a subject, again, coming from, I happen to come from the exact same town that he was born and raised in, in Dudley, England. So, it's always been a subject close to home for me, which is quite convenient because I love his movies. So, I'm hoping to eventually, hopefully plan a documentary feature on him, based on a lot of family material in the surrounding areas that I was able to hunt down, and forgotten histories about him and just put it together in some form, hopefully in the future.

Daniel: James Whale is the most known for his work for directing Frankenstein with Boris Karloff in 1931. But he also directed probably some of the most important horror films that have ever existed in the history of motion pictures. The Old Dark House, which can be cited with its very atmospherical, and black comedy tones, The Invisible Man with Claude Rains and Gloria Stewart in 1933. And, the most important one, which is probably the grand jewel in the whole of the Universal Monsters Empire, which is Bride of Frankenstein in 1935, which is the ultimate, example of everything that he had studied, everything that he'd learned with regards to cinema and comedy, life and death, and just making a very delicious cocktail of a movie in all of its black comedy, horrific, forms that we're still asking questions about today.

One of his first films that he did was for Howard Hughes Hell's Angels, in which -- because he'd coming over from theater -- when again, films in America were taken off with the sound revolution. They all of a sudden needed British directors to translate English dialogue better than the actors could convey.

So, James Whale was one of many to be taken over to America when he had a hit play called Journeys End, which became the most successful war play at that point. And he did his own film adaptation of Journeys End. He also did a really remarkable film called Showboat, which is another very iconic film.

And again, someone with James Whale's horror credentials, you just think, how could someone who directed Frankenstein directed Showboat? But, clearly a very, very talented director who clearly could not be pigeonholed at the time as a strictly horror director, despite it is the horror films in which he is remembered for, understandably so, just because they contain his very individualistic wit and humor and his outlooks on life and politics. And being an openly gay director at the time, he really was a force unto himself. He was a very modern man even then.