Get us started, since I know nothing about you, except that you wrote this terrific book. Tell me your background: Where did you come from? What do you do?

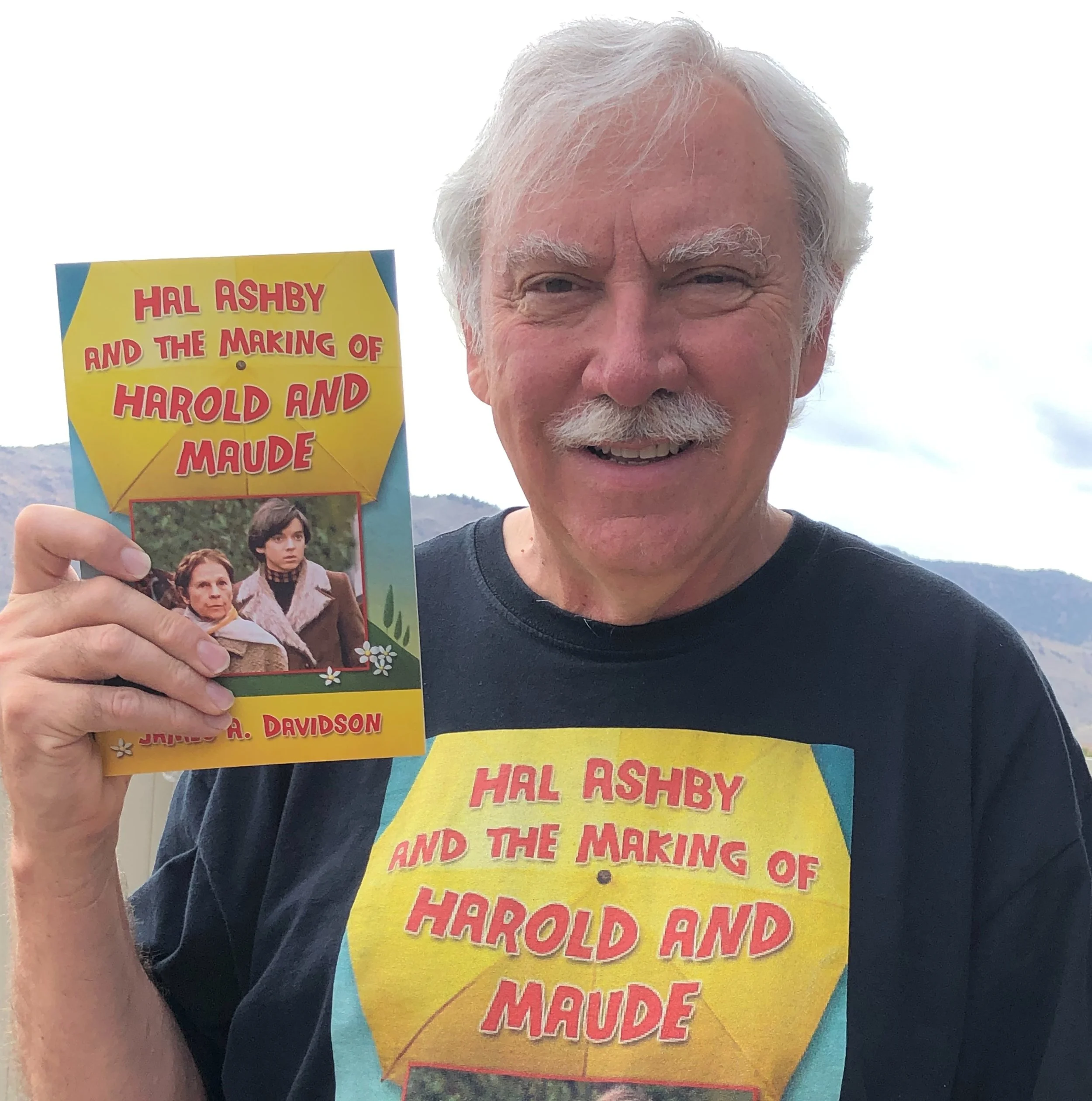

James Davidson: Well, I grew up in St. Louis in the 60s and 70s. I went to Northwestern University for the radio TV film program, started in 1976, and graduated in 1980. So, I have a bachelor's degree from Northwestern and that's where I kind of got my interest in film study. I had two classes where we wrote papers and were encouraged to study films with a scholarly approach to them, so to speak. Then when I got out, I didn't pursue any graduate work or take that any farther. But I continued, of course, to be interested in seeing movies.

I moved to the San Francisco Bay Area in 1981. It's really a great place to live in terms of film watching: the Pacific Film Archive and Berkeley, there's lots of great places in San Francisco to see movies. And it's also where Harold and Maude was mostly filmed, was filmed entirely, actually, I should say, although it's not really a movie that's associated so much with San Francisco, like Bullit or Vertigo.

I ended up starting a video production business and that's mostly what I did for 30 some years, but I just continued to be kind of an amateur film buff, sort of scholar on my own. I'm a big fan of Alfred Hitchcock. I co-administered a Yahoo Hitchcock discussion group for some years and that was fun.

Hal Ashby was just a long-time interest of mine. From high school, I saw Harold and Maude, and The Last Detail and Shampoo, sort of in a short period of time and I noticed that this name kept coming up in the credits as the director being Hal Ashby, who I'd never heard of. And, you know as well as I do that, before the internet came about, you know, it was difficult to get a lot of information about people. So, Ashby is kind of out there as this unknown figure to me. I mean, I got whatever information I could about him. But I really loved his movies and in the 90s, I did write an article about him in an online publication called Images Film Journal, just summarized his career the best I could and the movies. I hadn't seen them all at the time. Since the 80s, of course, some of them were kind of hard to see, you know?

They were. Looking To Get Out was a particular one for me. It's like, where can I find Looking To Get Out?

James Davidson: Yeah, I remember when it came out, and I saw an ad in the newspaper, and I thought, oh, great, a new Hal Ashby movie, and then it disappeared. Just like Harold and Maude, which disappeared very quickly from movie theaters. Same thing happened with Looking To Get Out and then it was available on a VHS tape for a few years.

Anyway, in 2009, a young writer named Nick Dawson wrote a very good biography of Hal Ashby and that sort of stimulated me to get going a little bit and maybe do some research on one of the films. I wasn't going to attempt to write a whole another biography, because Nick's biography was great. But in 2014, I just had some free time, I was working from home and I just decided, hey, you know, this is the time to do something. And Harold and Maude occurred to me, because it was a film that I knew that so many people loved and felt so strongly about, you know? So many people just seem to have a deep personal connection to Harold and Maude, and I felt like very little had been written about it.

Let's jump back. Can you think back on when and where you first saw Harold and Maude and what you thought that first time?

James Davidson: Yeah, I saw it on the first time it was rereleased. My parents had actually gone to see it when it first came out and I was only 13. I remember my mom coming home and telling me a little bit about it and I thought, well, what a strange topic for a movie which probably a lot of other people thought. But when it was released in 1974, and in a movie theater, it was given a major rerelease by Paramount in 1974, when it had been kind of growing in popularity. And a lot of college aged kids and colleges were requesting and renting the movie. And Paramount wisely, you know, to their credit, while they didn't handle the first release of the movie very well, they did continue to own the movie and they decided to give it a major rerelease in 1974, which is good.

It got out into the public and a lot of people saw it, including myself. I was 16 ,but a lot of people saw it I think then for the first time. And they rereleased it again a couple more times in the 1970s and I go over a little bit in the book how the money making was done and when Paramount's started making money on the movie. Which probably was much earlier than they told Colin Higgins and Hal Ashby and Ruth Gordon, all who had a back end on the profits from the movie. I found a very interesting letter to Colin Higgins from his accountant, written in about 1981, talking about Paramount and what they were telling him about the profitability of the movie, when the movie was going to make money. He seemed to be a little cynical about the expenses they were writing off on the film.

When you saw it for that first time, in that big re-release, what did you think?

James Davidson: I adored it. I mean, I thought it was a great movie. I wasn't offended at all by any of the subject matter. I thought it was funny. I thought it was touching. I thought it was serious. It had this wonderful way of going along between the serious and the comedic. I thought it was a superb movie and I was seeing a lot of great movies at that time. That was the time, when we were in high school, was a really good time for movie making.

I probably saw it a month or two after I saw Chinatown, which is one of my favorite movies and came out that summer of 74. But yeah, I adored it and I like Cat Stevens’ music, had been a Cat Stevens fan for several years and his music really enhanced it. And I was just curious about the movie for many years because, like I said, there wasn't much written about the movie, you know, where did this movie come from?

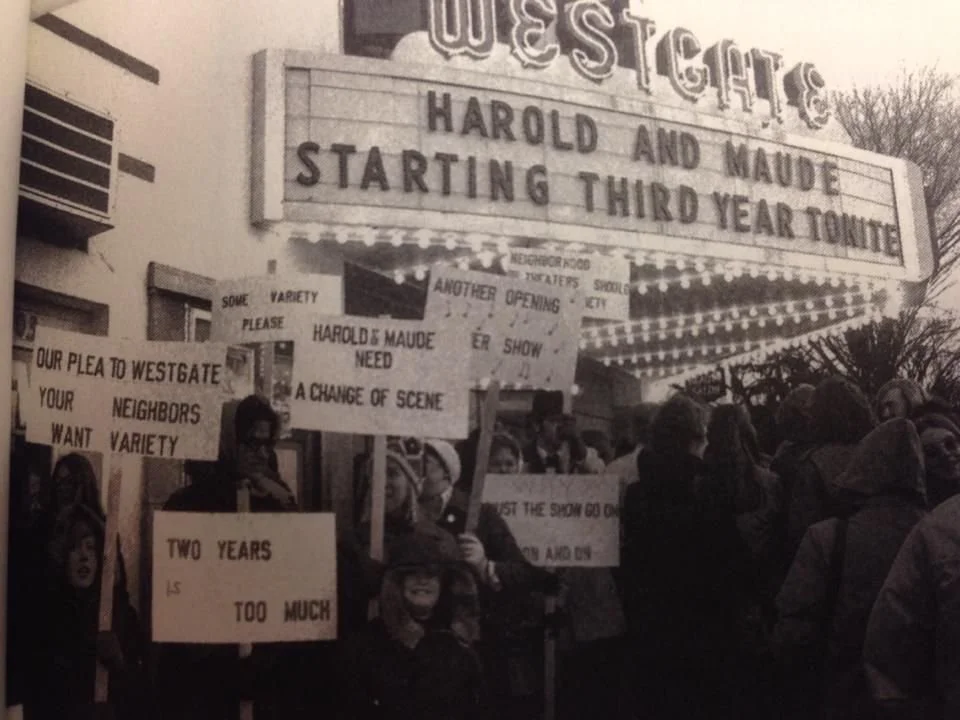

It's famous, or infamous as a movie that people see again and again and again. You know, it ran here at the Westgate theater in Minneapolis for over two years. At least one young man who at the time had seen it 150 times, I think and that's during its two-year run. How many times have you seen it?

James Davidson: That's a good question. It's hard to answer. You know, like a lot of people when I saw it in 74, then it was rereleased again, I think a couple years later, I saw it again on its re-release. But I didn't go multiple times. I mean, what I would do would be to take people and go, have you seen this movie? So, I’d go to see it with various friends of mine. I saw it probably in college, must have seen it once or twice, you know, and then when it was on home video, I bet I've seen it a couple dozen times.

So, you said that you had some time on your hands, I think in 2014, and you picked Harold and Maude as something to dive into. What was your research process, because even at that point, a lot of the main players on and off screen were gone? So, how did you approach it?

James Davidson: I started out by going to the Margaret Herrick library, which is in Beverly Hills, and made a trip down there. My wife and I made a trip down there and I did an initial day of research there, going through the files on the movie. And then I did a second trip. We lived in the Bay area at the time. So, I did a second trip down to Los Angeles shortly thereafter, because I hadn't gotten everything I needed. You know, I attempted to reach out and contact as many people as I could. Hal Ashby has been dead for a long time. Ruth Gordon, Colin Higgins, they've all passed away. I attempted to solicit Bud Cort for some help on the book. He was not responsive.

He is famous for that.

James Davidson: Yeah, and that sometimes happens. You know, it's hard to get people to participate even for a simple interview a lot of the time. I did contact Nick Dawson, who had written his biography on Hal Ashby and Nick was very helpful. Nick gave me all of his research notes to use, which were very helpful.

And I did get a hold of Jeff Wexler. He had worked on the movie as a kind of a prop master and general assistant to Hal Ashby and he was very helpful because he'd been there all through the making of the movie. The actors and some of the other people were there for a few days and Jeff was pretty much there the whole time. So, he was very helpful.

I talked to the woman who was Ruth Gordon’s stunt double, her stand in. I talked to her on the phone and talked to a fellow who was a just had a bit part in the movie. And I had some emails with Ellen Geer, who played Sunshine in the movie and Ellen gave me her recollections of the film. But it was a long time ago and, you know, for a lot of these people it was a week or two work, you know.

Nearly 50 years ago. What were you doing at work 50 years ago on a Tuesday?

James Davidson: Eventually my wife helped me locate Tom Skerritt who lives up in Washington State. Towards the end of my process, Tom gave me a call which was very nice of him. We talked for an hour or so about how and about the movie and that was great.

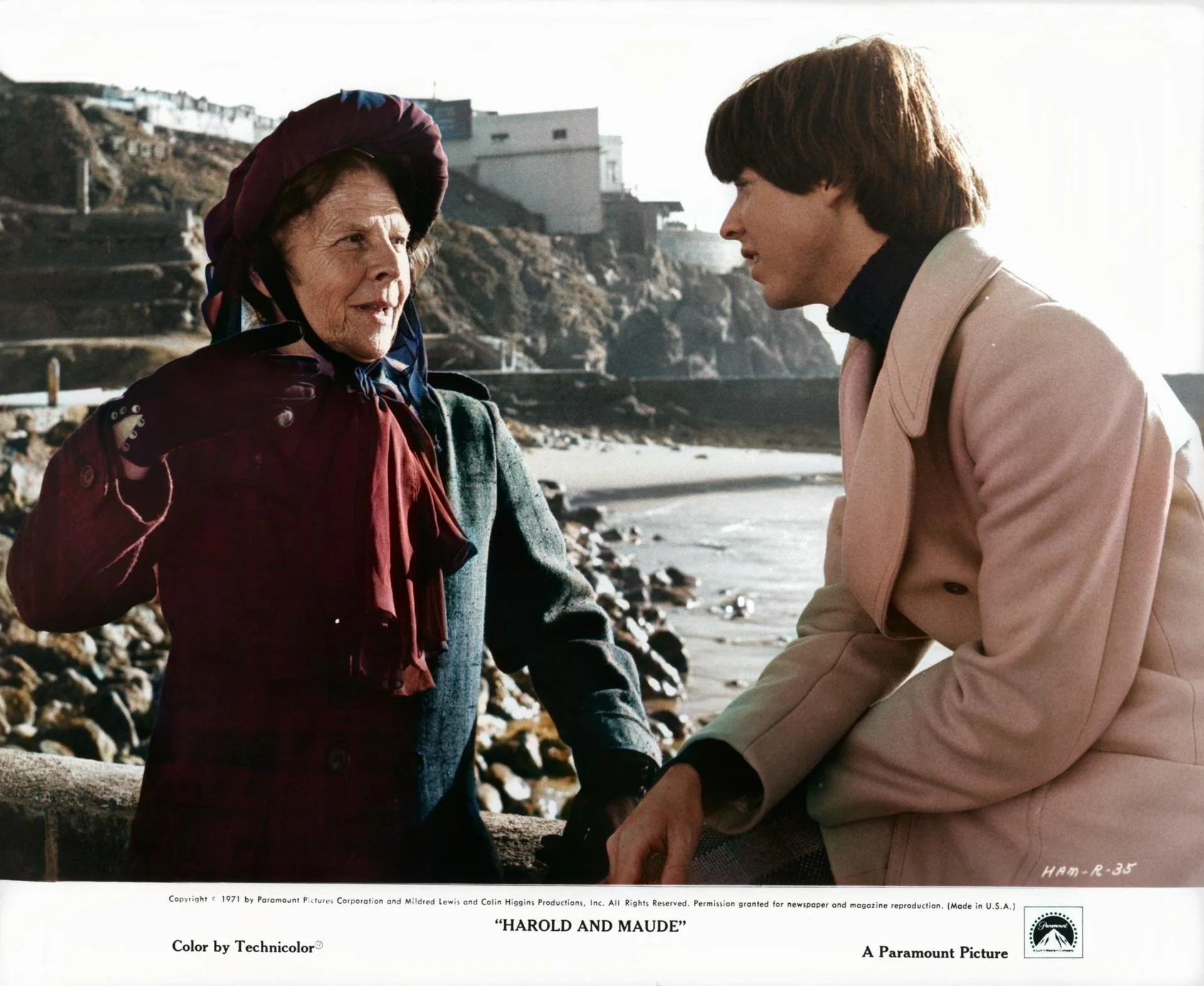

Your discussion with him that you touched on in the book, confirmed for me something I've thought for years. Because it took me a while to piece together who this M. Borman was in the film. And then I realized from the voice that it was obviously Tom Skerritt. And then in watching his scenes with Ruth Gordon, there's at least one point, maybe two, where he says something to her and her response has no connection with what he just said. And I realized finally, and you confirm that for me, that he was improvising with her. And Ruth Gordon doesn't do that. Ruth Gordon says the lines that were written.

And to have kept that in just added to their scenes together: he was on one plane, and she was on another. And I just think it's part of Ashby's genius that he allowed for that confusion for an audience member to go, he's saying one thing, and she's saying another, why is that? Did he talk about that at all?

James Davidson: Yeah, he talked about it to the extent that, you know, he was called into the movie kind of at the last minute. He wasn't supposed to be in it. I cover that in the book and I did find out some of the reasoning behind that. It’s in the book. It's one of the more interesting stories.

Just tell us quickly what happened to the poor actor who had the part before him?

James Davidson: Yeah, he cast an actor, his name escapes me at the moment, but he was going to play the motorcycle cop. The first time they got rained out. The second time they tried to shoot it, he took off on his motorcycle, and the motorcycle crashed because he hadn't put up the kickstand. And when he did turn it, it hit the ground. Very rough and he was hurt. He wasn't seriously injured or a long-term injury, but he couldn't be in the movie.

So, then they put the scene off again and then the last-minute Hal persuaded Tom Skerritt to come up from LA and do that part. So, Tom got the part at the last minute, he had to kind of come in quickly and learn his lines quickly. And he is just a more of an improvisational actor, and just came from a different generation and a different mindset for acting than Ruth Gordon did, who was a well-known Broadway actress, and you didn't diverge from the lines. A lot of the time she was doing, you know, Eugene O'Neill or somebody like that, and you're not going to start improvising on him. In this case, it was Colin Higgins.

And then there was also the issue of the fact that she couldn't really drive a car very well. So, her stunt double had to do a lot of her driving. So, a lot of the part where she's driving is her stunt double who is 20 years old. They created a rubber mask of Ruth Gordon's face for this young woman to wear while she's driving.

And it also explains why even when it's not raining, Maude will put up her hood before she starts to drive.

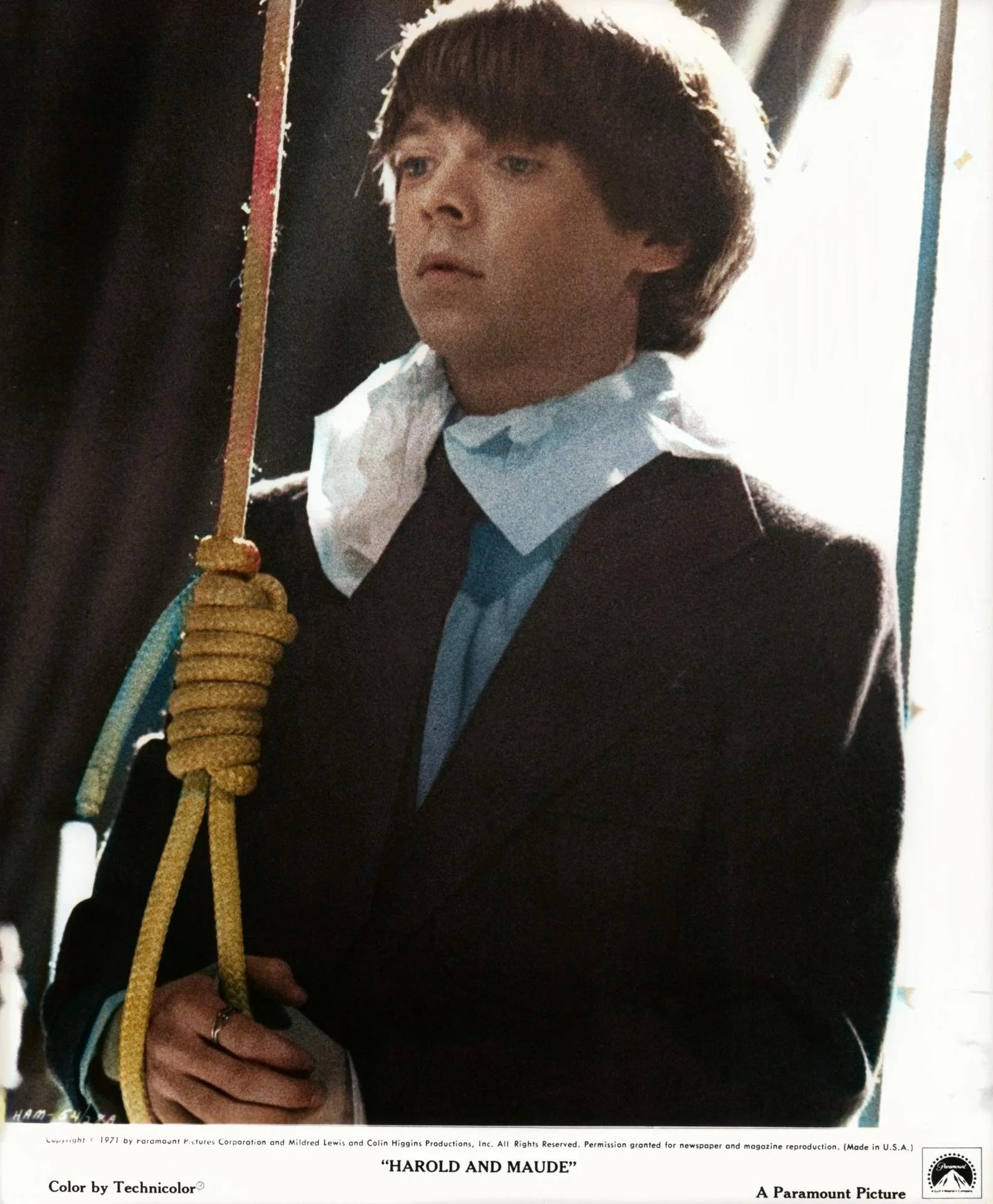

One of the other things you mentioned that it took me a long time to notice—and I am one of those people who'd seen the movie a lot—was during the motorcycle scene, the last one with Tom Skerritt, Bud Cort whacks himself pretty seriously in the side of the head with that shovel. And once you see it, you can't unsee it.

James Davidson: Right. I had never noticed that in seeing the movie and it was brought up while listening to the commentary on the blu ray. He doesn't break. He carries on the scene and Hal used it in the movie. It adds a degree of realism.

It does. I mean, they had to get going and so he just kept going. Was there anything else you found out in your research that sort of surprised you that you hadn't noticed before?

James Davidson: I guess one thing that surprised me was I ended up going back to UCLA to the Special Collections Library at UCLA. And I went through Colin Higgins papers. They're all held at UCLA. Hal Ashby's and the production notes are at the Beverly Hills at the Margaret Herrick. But it was really useful to go to look through Colin Higgins notes.

I guess one of the more interesting things about it is the fact that Higgins was a graduate student in UCLA. And he wrote this script intending it to be just a 20-minute student film. It was the last of his three scripts that he'd written. And then with the encouragement of a lady named Mildred Lewis, he expanded it to from 20 minutes to a full-length feature. And her husband Ed helped sell the film to Paramount.

And the film really got produced almost as it was, in the way he had initially written it. It’s kind of crazy to think that and I think it probably only could have happened at that time, in the New Hollywood era in 1971, that a script could get written by such a novice to screenwriting from an original not from any source and be taken almost word for word and transferred to the screen. No changes were made, there weren't any rewrites of any significance that I could find. The film was more or less made by Paramount the way he'd written it.

I was surprised there'd been a short script. I didn't know it started that way and I was really surprised that the very first scene in the movie, the long continuous shot up to Harold hanging himself, is right there in the short, described exactly as it ended up being in the film.

James Davidson: As a matter of fact, Higgins said the reason he knew he could do it as a student film is that he found a place that would rent him a camera and crane that was all in one, so that he could do that shot where the feet get followed and then the camera lifts up to be behind Harold as he hangs himself. But yeah, that's the one constant as he expanded it. I mean, the finished one is quite a bit different from the original one. Although the central story of Harold and Maude meeting and falling in love is the same basically. He did expand quite a bit. He added a number of characters. He had the entire bit about the computer dating and the three girls. He added that a lot of Uncle Victor, I don't think Uncle Victor was a character, he wasn't a character in the original.

Was Glaucus in that, in the original short too?

James Davidson: Glaucus, yes, Glaucus was. I think his name was different. But yeah, he existed at the beginning, because they needed somebody to kind of help them with some of the things that they did. But yeah, Glaucus was in it.

That was another thing that always puzzled me before I could find out anything about Harold and Maude was Why is Cyril Cusack so highly billed? And he has one line, which is I think, “whatdya want?” and even I knew that he was a pretty well-known British stage actor, because the theater I was working at the time when they stopped running Harold and Maude were running some Pinter films, and he was in one of those. So, it always puzzled me as to why would an actor of that stature come all the way to America to do one line. And then of course, I find out that because Hal Ashby got started as an editor, he was pretty fearless in editing.

James Davidson: Yeah, the original cut of the movie was three hours long, which is kind of amazing. If you think about it, it ends up being 91 minutes. And yeah, there were a number of Glaucus scenes in the in the script that were cut completely. And he apparently really tried to keep some of them in, but they just didn't work as they were. So, he ended up having to eliminate almost all of them except for that one scene where Harold comes in and she's being sculpted in the buff. And even then, his part is very brief and then they talked about him a few other times.

And then the other thing that was kind of surprising was there was an entire character that was completely excised from the movie, Madame Arouet. She had a pretty significant part in the original script. She's in a lot of the scenes with Maude and he just felt the character was unnecessary and it just got cut and cut and finally ended up completely excised from the movie.

Hal made some good decisions about he reordered some of the scenes, because there's a lot of discussion between him and Robert Evans, the production chief of Paramount that I found where he talks about the importance of getting Maude into the movie early enough, so the audience doesn't lose interest. Keeping her scenes, the right order so that you know, we don't lose track of Maude, because we do get off onto a lot of Harold stuff at various points with the computer dates and Uncle Victor.

But he does a great job of really keeping track of Maude and developing their relationship over the course of it's just a few days in the movie, of course, but really well done. I mean, he was such a brilliant director and I could go on and on about Ashby. There's a great documentary that Amy Scott did about how that, I'm sure you've seen. It's great that even you know, of course it's very posthumous. But you know, he finally gotten some attention with the biography and the documentary. Really nice that finally some attention has been paid. His films are so great, and unfortunately his demise was kind of quick and he's just never got the opportunity. I talked about that in the book a little bit. He didn't get the opportunity to get that career renaissance, you know, while he was alive to get that real appreciation, which he would have if he if he lived.

So, I'm guessing that if there was anyone you could have talked to who was gone by the time you started his research, it would have been Hal. Who else would you really like to have been able to at least ask one question of and what would that have been?

James Davidson: Well, I tried to contact as many people as I could. I would have liked to have had Charles Mulvehill, who was Hal’s associate producer contribute to the book. For whatever reason he didn't want to. And there were several questions at the time about things that happened during the making of the movie. There was one particular incident that I could only find sort of peripheral information about that had to do with some conflict with Paramount over a driver: somebody had called in the middle of the night and woken everybody. I touched on it in the book, but I couldn't get all the details that I wanted. That kind of thing is helpful to have, you know, people to get clarification on what exactly happened. There were a lot of the people though, that either I couldn't get or wouldn't participate in the book.

A lot of them though, are on the record quite a bit for various interviews, and what not. Robert Evans and Peter Bart, both of whom were the Paramount production people, they've been interviewed extensively about the movie and the process of how it came about. I would have liked to clarify one thing: Peter Bart has said that there was a meeting before the movie started production where Hal Ashby came in with Cat Stevens, and they talked about making Harold and Maude into a freaky musical and this and that. I just don't think that happened the way he remembers it. Stevens was not picked to be the musical part of Harold and Maude until they were really making the movie. They were in San Francisco shooting it and he only came to the set in San Francisco where they were filming. So, I think he's remembering that wrong.

I do have one question about that and maybe you can answer it because, you know, we know that Cat Stevens came into the project late. They were still shooting and he did come up with two songs and one of them he taught to Ruth Gordon. But what's always puzzled me was—it's just such a dumb film techy question—when it came to Don't Be Shy, which Cat Stevens has said along with, If You Want to Sing Out, Sing Out, were both essentially demos that he gave them thinking he was going to redo them later with more instrumentation. Don't Be Shy is exactly the right length for what happens in that shot. And I've always wondered: Did they have it when they shot it? Did they say to Cat Stevens, this is your slot, you need exactly X number of minutes? Do you have any idea how that worked?

James Davidson: I can't say for certain that I got out of anybody's mouth. But my guess is that no, they didn't give Cat an exact time and say, hey, you know, Don't Be Shy needs to be three minutes and 12 seconds or whatever it was. My guess would be that Hal edited the sequence to the song.

But Jim, it's all one shot. From the time Harold puts the needle on the record until the time that he kicks his foot off the stool and you can hear the rope swinging as he swings. The song ends at that moment. Which is why it's always puzzled me as to, you know—and it's like I say, it's a stupid film geek question. Did they get lucky? Or did they already have the song? Or what? So, it may be one of things will never know.

My other question that I would ask if I had Hal Ashby sitting in front of me and again, it’s another stupid question, is the point in the movie which the people in the Harold and Maude world called The Look, which is when Harold breaks the fourth wall and looks right at the camera. To my eye, it appears to be in slow motion. If you look at Vivian Pickles, she blinks, I think Harold blinks. It's clearly been slowed down a little tiny bit, which would have been something he would have had to do in post yet. Again, stupid film geek thing, you know, this is 1970-71 when they shot it. He would have had to make an inter-negative of it to do that and like all special effects at that time, there would have been a slight shift and there is none. Do you know anything about that moment?

James Davidson: I really don't. I know, they said that it was not planned, that it was improvised.

Well, next time you see it, look at it. I believe it he actually switches into slow motion in order to draw it out just a little bit longer to make that part work. But again, because it's over 50 years later, we're just never going to, we're never going to know. Do you have a favorite moment in the movie?

James Davidson: The closing sequence, the intercutting, between her going into the hospital and him waiting all night and then driving to the point in Pacifica, where the car goes over. And that was not done in the script that way. That was not written in the script that way. That was all done by Hal in the editing room.

Because there was dialogue in the hospital and that's clearly been cut.

James Davidson: Yeah, I love that sequence and it's set to of course very great piece of music, Trouble by Cat Stevens. And it's just a really, it's a great way to conclude the movie. And then you get the car going over the cliff, which they apparently had a lot of trouble with and there is that awkward still, which I guess he had to do. Again, that would be that would have been a good question to ask Hal, you know, I guess that had to be done maybe to match sound or something.

I think he was just trying to draw the moment out so that it was more of a moment that you had to watch.

James Davidson: Apparently, they only had one camera that got the—they had a ton of cameras shooting it—but there was some problems with starting the shot and some cameras rolled and other cameras didn't and some cameras had malfunction.

Yeah, that's every filmmaker’s nightmare.

James Davidson: And especially on that one scene where the car gets wrecked. Now, I should mention about the car that, after the book came out, I didn't have a lot of information about the car but after the book came out, I was contacted by a gentleman named Don Kessler and he works for a man who actually recreated the Harold and Maude hearse/limo. This gentleman expended quite a bit of money, doing an exact reproduction of the limo hearse. And he brought it to, we had a book signing in 2016 at the Western Railway Museum, where the rail cars located that was Maude's home. They brought the car, and I did a book signing and people could go through and tour the rail car.

Is the rail car still set up as her home?

James Davidson: It's not set up as her home like it is in the movie. Everything was taken out that they put in and it was reverted to what it is, which is a 1930s Pullman or something railcar. But the core of it, the carpeting and the some of the glass, things like that they are still there. You know, obviously a lot of the objects are taken out.

Right! Is there something that people often just get wrong about the movie that you think the book might help correct?

James Davidson: Well, one thing comes to mind, which is that some people have speculated that Cat Stevens does a cameo in the movie. And that's wrong, because the scene that they point out that he appears to be in was filmed before really Hal had even made a final decision on Cat Stevens being used. It's the scene at the at one of the funerals and she is standing there, and the camera looks across at her, at Maude, and there's a man standing near her who appears to resemble Cat Stevens: has a black beard and looks a little like him. And the timing of when that scene was shot, it can't be Cat Stevens. Aside from the fact that there's just no record of it. So that's, that's a minor point. I think that people get wrong.

Since the book has come out, since you wrote the book and it's been published, what else has come to light? Or who's approached you with new information? Or what has the book done to open up the world of Harold and Maude even more for you?

James Davidson: The most significant is Don contacted me about the car and all the work that was put in on the remake of the car. And they had some information about the original creation, the original Perce Jaguar car, you know, that they just couldn't be that forthcoming with it. It was apparently made by the same carmaker that made the Batmobile and some of the other crazy 1960s cars. I would have liked to have had more detail about that. I have talked with him some about it. I mean, I would probably if I was doing the book again, I would have more of an expansion on that.

Second edition? We need a second edition.

James Davidson: Yeah. Maybe it's not a huge part of the movie, but it is an interesting part of the movie.

And very well remembered by everyone.

James Davidson: Yeah, Colin Higgins originally wanted just a little British roadster, an MG. And Hal and the production designer for the film decided that a Jaguar would have more kind of punch, because they were very popular at the time.

You know, when the two-year anniversary of Harold and Maude at the Westgate happened here in Minneapolis, I was still in high school. But I had access to a lot of film gear, a lot of Super Eight film gear. And I also knew people who were working on the celebration. So, I was able to pretty much follow Ruth Gordon and Bud Cort around for the two days they were here and shot a documentary. I'll put a link to that in the show notes and I'll send you a link you can see. It's primarily looking at what they did when they got to the Westgate Theatre, but I did follow them around for two days. They would go from a press thing and I would run and get on a bus and try to follow them to the next press thing.

But because I knew the son of the film critic at the Star Tribune paper, I got to go to dinner with him and with Bud Cort. I don't remember a lot of it and I wasn't savvy enough to ask the right questions that I should have. Just because you know, I was 14 years old, 15 years old. What do you want? Give me a break. But I do remember Bud Cort saying the question that he is asked most frequently by anybody anywhere is, Did you really crash the car? And he would always say yes, the car is really crashed.

And so, all these years later, more than 50 years later, you've literally written the book on Harold and Maude. Why do you think it's survived and why it's so popular?

James Davidson: Well, people just are so personally responsive to the movie. They love it on a personal level. And I think that has something to do with the philosophy of Maude character. And a lot of people connect with that.

A lady came to the book signing who had a shirt that she'd made up that had some of the quotations that Maude makes in the movie. And you know, somebody brought Oat straw tea and ginger pie. They had a lot of these things. They really take it personally. They love those little touches. They feel a deep connection with both the Harold and the Maude characters.

And it maybe says something that, you know, this is a movie that's about death in a way and fake suicides and is a little morbid sometimes and has severe black humor to it, but people connect with it personally.

They love it and it's a great movie and it's a wonderful film and it's just got some quality that everybody connects to.

Dying to make a feature? Learn from the pros!

"We never put out an actual textbook for the Corman School of Filmmaking, but if we did, it would be Fast, Cheap and Under Control."

Roger Corman, Producer

★★★★★

It’s like taking a Master Class in moviemaking…all in one book!

Jonathan Demme: The value of cameos

John Sayles: Writing to your resources

Peter Bogdanovich: Long, continuous takes

John Cassavetes: Re-Shoots

Steven Soderbergh: Rehearsals

George Romero: Casting

Kevin Smith: Skipping film school

Jon Favreau: Creating an emotional connection

Richard Linklater: Poverty breeds creativity

David Lynch: Kill your darlings

Ron Howard: Pre-production planning

John Carpenter: Going low-tech

Robert Rodriguez: Sound thinking

And more!

Write Your Screenplay with the Help of Top Screenwriters!

It’s like taking a Master Class in screenwriting … all in one book!

Discover the pitfalls of writing to fit a budget from screenwriters who have successfully navigated these waters already. Learn from their mistakes and improve your script with their expert advice.

"I wish I'd read this book before I made Re-Animator."

Stuart Gordon, Director, Re-Animator, Castle Freak, From Beyond

John Gaspard has directed half a dozen low-budget features, as well as written for TV, movies, novels and the stage.

The book covers (among other topics):

Academy-Award Winner Dan Futterman (“Capote”) on writing real stories

Tom DiCillio (“Living In Oblivion”) on turning a short into a feature

Kasi Lemmons (“Eve’s Bayou”) on writing for a different time period

George Romero (“Martin”) on writing horror on a budget

Rebecca Miller (“Personal Velocity”) on adapting short stories

Stuart Gordon (“Re-Animator”) on adaptations

Academy-Award Nominee Whit Stillman (“Metropolitan”) on cheap ways to make it look expensive

Miranda July (“Me and You and Everyone We Know”) on making your writing spontaneous

Alex Cox (“Repo Man”) on scaling the script to meet a budget

Joan Micklin Silver (“Hester Street”) on writing history on a budget

Bob Clark (“Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things”) on mixing humor and horror

Amy Holden Jones (“Love Letters”) on writing romance on a budget

Henry Jaglom (“Venice/Venice”) on mixing improvisation with scripting

L.M. Kit Carson (“Paris, Texas”) on re-writing while shooting

Academy-Award Winner Kenneth Lonergan (“You Can Count on Me”) on script editing

Roger Nygard (“Suckers”) on mixing genres

This is the book for anyone who’s serious about writing a screenplay that can get produced!