Gaspard: So, thank you for talking to me. I could talk about every single movie you've done. But I'm not going to do that. I have focused myself to take principles from the two books, both of which I love, and take some of those principles and see how you applied them in different situations on three different movies. So, just to get some background to make sure I've got the history right, your first TV directing gig was on The Bold Ones, right? The Senator.

Badham: Yes. Yes, that's right.

Gaspard: And then your first TV movie was The Impatient Heart.

Badham: Right, right, yes.

Gaspard: Okay. So, I'm just doing some rough figuring and before you shot Bingo Long, which was your first theatrical feature, you did somewhere between 35 and 50 hours of TV. You had a lot of stuff under your belt before you tackled that theatrical feature, because of all the series you did, and the Made-for-TV movies. So, you were pretty well learned by that point for that first feature. How did that help you on that first one?

Badham: Well, it certainly helped you learn how to prepare things, what you needed to do, and working with actors, getting attuned to working with actors. The mechanical parts of it are fairly easy to learn—

Gaspard: Right.

Badham: —the cameras and lenses and the microphones and the lighting and and stuff like that.

I feel very comfortable just from my years at the Yale Drama School, working in theater where you're doing somewhat analogous things along the way. And then as I was working my way toward directing—once I came to California and was working at Universal—I was able to sneak down to people's sets and meet directors and kind of hang out with them and found an interesting approach. Because, initially, going and hanging out on a set sounds like a lot of fun. And it's good for about 10 minutes and then it is just boring as hell.

And I realized I don't want to, this is boring. What could I do better? And then it came to me: The truck just ran over the director, and I have to do it. What am I gonna do? So I would get hold of the script and try and prepare the day's work roughly, and then come down and be able to watch what the director was doing.

And it didn't matter who was right or wrong. What it did matter was because I had thought it out. I had a basis on which to judge, you know, was it a good idea they were doing, what stuff would I have forgotten? I just learned by watching that that way.

And so, after, four or five years of doing television, I was pretty well versed in a lot of high speed, quick filmmaking for, episodic television in particular. But then the movies of the week, you know, were a nice step in between. There you had a chance, you're still working quickly, but not nearly at the silly lightning pace of the episodic.

Gaspard: So, was the speed at which the features were shot, was that easy to ease into? Or were you always just thinking, why is it going so slowly? Why aren't we going faster? Why, why, why, why?

Badham: Yeah, it seemed to me on, on Bingo Long where they said, well, we're going to shoot this in 38 days. And I thought, 38 days, what am I going to do in the afternoon? Oh my God, I can go home after lunch. We'll get this. Well, little did I know how long camera would take and baseball games to shoot and stuff like that. And the production manager kept telling me, “it's going to be 52 days.” And I said, “No, no, we promised 38, that we would do 38. I'm going to do it.” “No, it's gonna be 52.” Because he was right. It was 52, right on the money.

Gaspard: Yeah.

Badham: He knew it. So, I just had to regear my brain. Same thing on Saturday Night Fever. Same 38 to 52 days, you know, just me getting to understand what that next level up of filmmaking requires. And in terms of the detail of the filmmaking and the careful performances and things like that.

Gaspard: When you look back on, on the hours and hours and hours of, you know, on the job training you had before that first feature … and then you think about directors starting out today, who simply don't have that, getting all that experience is hugely helpful. And I know you've taught for years. What, advice do you have for someone who's diving into a feature for the first time who doesn't have 40 hours, 50 hours of finished TV work under their belt?

Badham: They're in a lot of trouble. That's what the truth is. You know, it's so much harder than it looks. And I see that with my students, with the filmmaking that they come up with. It's really difficult to learn it. And the thing that turned out to be really good in my case and some other friends of mine is that we got a lot of practice and learned how—if we stubbed our toe—it was not the end of the world. That you could get through it, because it is harder than it looks.

And they've got a great, harsh awakening coming for them. You know, I've worked with several cameramen who've become directors. And of that, several, almost all of them, never did it again. It drove 'em crazy, and they were brilliant cameramen. You know, these were top of the line, the best guys in the world. And they said, “oh my God, we're going to get a so-and-so to direct this.” And they hated it, because you had to deal with actors. And they were used to a crew that would just jump: If you, said jump, and you know, how high? Ten feet. They'd jump 10 feet. But the actors are going, “What?” They didn't like that.

Gaspard: That's your special gift I think. You can direct action like nobody's business, but when it comes to getting an actor where you need them to be, I mean, you, straddle both sides really, really nicely. I do want to talk about Isn't It Shocking? I don't know why I know it as well as I did. It must have aired at least twice when it came out. And that's around 1973.

Badham: Right. Yes.

Gaspard: I know that I was a big Harold and Maude fan, so I wanted to see Ruth Gordon in something. But I was really taken by it, and it stayed with me for years and years. And I found it recently on YouTube. You can see the whole thing on YouTube, not a terrible print of it. And some questions came up. First: one of the first credits on it says David Shire did the music. How did that happen?

Badham: I was at Yale when David was there and worked on two musicals that he and his partner Richard Maltby wrote. And, so we were friends from there and I was, you know, excited to be able to bring on a composer. I think it was the first one that he had ever done, the first film he had ever done. I mean, he might've done some low budget things, but my recollection is, that he had been playing the piano for The Fantasticks off Broadway forever and ever. That was his day job.

Gaspard: How did Isn't It Shocking? come to you?

Badham: I think my agent at the time was able to talk two very young producers into taking a look at work that I did, which was at that point, I think. The Impatient Heart was probably what they might have looked at, at that point.

And, it was just a wonderful script, you know, it was just laugh-out-loud reading and so much fun to do. And we shot it really quickly, like in 12 days up in Mount Angel, Oregon.

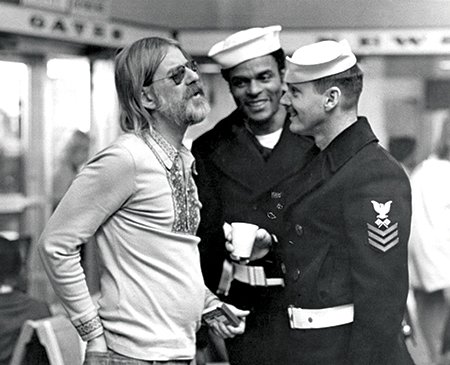

Gaspard: The casting of it is so terrific. You know, besides Ruth Gordon, you've got Will Geer, you've got Alan Alda, you've got Louise Lasser, you have Lloyd Nolan. I know you kind of started out in casting and you've consistently had really smart casting on all the movies. Do you remember how that cast came together?

Badham: Well, my producers were New York based and they had a great sensibility for actors, like Louise Lasser, who I didn't know at all. Will Geer I certainly knew, and Lloyd Nolan I had worked with. Alan Alda was, you know, we all admired his work and thought we were really lucky to get him right at the end of the MASH season.

Gaspard: Yeah, it looks like was right at the end of the first year of MASH.

Badham: Right. And we were shooting on the lot at Fox where MASH shot any anyway, so I was able to go over visit with him and talk with him and get to know him. But, as I say, my producers were very helpful because they were just into every detail. They were over my shoulder, breathing down my neck in the middle of closeups, you know, “We need more goop on them. We need, this is not goopy enough. “

Gaspard: Goop is very important in that movie that you needed enough goop, because it gets bad when he runs out of the goop,

Badham: It drove me a little bit crazy. And, at one point, as they're whispering in my hair during a take, I call “cut.” I reached for my wallet, pulled out my Director's Guild card and said, “Here, you fucking do it.”

Gaspard: Oh boy. You know, this is at least two or three years before Mary Hartman. So, at that point Louise Lasser is from Bananas and—

Badham: A couple of Woody Allen movies.

Gaspard: Yeah, a couple Woody Allen movies, but not that famous. It felt to me like this could have been a backdoor pilot, that if MASH didn't go, here we have these two wonderful characters of Louise Lasser and Alan Alda solving crimes every week. With, you know—not that Ruth Gordon wanted to do a TV series—but it would've been a fun way to continue those characters. Because they were really charming together.

Badham: They were wonderful. And we forgot about Eddie O'Brien.

Gaspard: Oh, exactly. He looks so upset in that movie. It's hard to watch him sometimes.

Badham: I had seen him in a pilot that Jack Lord was starring in, and he played a bad guy. He had these thick coke bottle glasses on, and he was quite a treat. He was quite a handful. Because he wasn't always very focused and sometimes getting him off, “Okay, that's that shot, now we're going to focus on this shot.” And he's still back in the earlier shot.

Gaspard: Well, you were juggling so many different kinds of acting styles, and that's one of the things that I want to talk about from the book: When you have, you know, in one scene, an Alan Alda, Louise Lasser and a Lloyd Nolan. I'm guessing they're acting styles were a little different, or their approaches were a little different. How do you juggle different techniques when you need to get everybody on the same page pretty quickly?

Badham: It's a real challenge to do that because you have some people that like to rehearse a lot. Some people that don't like to rehearse very much at all. Some people that are good on take one and other people who don't start to get good till four or five. And you're going to find, every single time, you're always going to run up against these disparate characters.

If they haven't worked together a lot, you're now trying to massage. You know, “Am I going to shoot Will Geer first in this scene? Or am I going to wait because he gets better later on?” And if I shoot over his shoulder, he is kind warming up, so when I'm ready to turn around onto him, he's at that good cooking point. He's simmered, you know, he is done. You can stick a fork in him, and it will be all right.

Gaspard: That's invaluable knowledge to have when it comes to planning out your day and your setups.

Badham: Oh yeah. I mean, once you start to get a fix on how the people like to work. I learned once from Jodie Foster—I worked with her when she was very young and we were kind of become friends—and I was asking her how she likes to work with actors. She said, “The first thing I do, is I go up and I ask them how they like to work?”

You know, do you like notes from the director? Do you like to go first? Do want me to let you move, find your own blocking? And just kind of having these conversations lets you know a ton of stuff. Elia Kazan talks about it all the time in his book, saying actors will tell you anything, you've just met them, and they'll tell you their entire life story in a few minutes. And you can learn so much about their acting style, just from the stories that they tell and their perspective on the world. And you're so smart to be able to go and have dinner with 'em a couple of times, to sit with them and just not talk about the business, but just their life and understand, you know, what you may be able to get from 'em.

Gaspard: That’s so smart. Just that idea of, well just ask him. You don't have to pretend to know everything. And that's one of the things you keep coming back to in both books is: don't pretend to know everything. Ask, ask. And that's so smart to just ask them the way they want to do it.

A friend of mine was one of the editors on Veep. And he said it took them a little while in that show to realize that, you know, most things are shot, you do a master and then a closeup, and a closeup and a closeup. And he said it doesn't work on an improv show. You have to do all your closeups first until everyone's sort of settled into what they're going to do. And then you do the master at the end, because that'll match. He said, you do a master up front, it's not going to match anything you're doing. And it's like, well, duh, obviously. But we're so attuned to this idea of, well, you know, you start out and then you move in and move in. They just turned it on its head and went, no, it's got to go the other way. Or the master is just useless.

Badham: Right. Well, those are outrageously funny.

Gaspard: So. speaking of improv, you mentioned I think in one of the books, one of my favorite Ruth Gordon stories. I was lucky enough to meet her when she came through town here in Minneapolis, Harold and Maude played for two and a half years, when I was a teenager. And I got to meet her and Bud Cort and hang out with them a little bit during that time. And in one of the books you talk about, where she came up to you and said, “This line isn't working for me.” And you said something along the lines of, “Well just, you know, say what you want.” And do you remember what her response was?

Badham: Oh yes, absolutely. I said, “Well, Ruth, what would you say?” And she looked me right in the eye, kind of waggled her finger and said, “Oh no. I get paid for that.”

Gaspard: Yeah.

Badham: And she went ahead and said the line as written, the one that she started out complaining about.

Gaspard: A couple more things on Isn't It Shocking? There's one point in it where Alan Alda is walking through, I believe it's Ruth Gordon's home. And you did—for that movie—a pretty long continuous shot. Now you said you shot in, was it 12 days?

Badham: Right.

Gaspard: How risky did you think it was? Maybe you did do coverage on it, we just didn't see it. But when it comes down to setting up shots like that, what are you weighing in your mind when it comes to how much time I have and what I need to get done today, and continuous shots versus a lot of coverage?

Badham: Well, you know, usually the continuous shots, you can get several bits of coverage in the shot itself. And so if you write down the amount of time it takes to do a continuous moving master versus a lot of separate shots, it works out about the same.

Gaspard: Okay.

Badham: It's just a different way. And in that particular shot, if I remember it right, we pick up Alan Alda coming in the front door and then as he's walking through, there are cats hanging everywhere and cats dropping down out of the ceiling onto him. And you could see them hanging on light fixtures. They're all over the place. And I,remember our production manager had an arm full of kittens and he's walking behind the camera, putting them up in all these places and you could see them kind of hanging on by the front paws or whatever it was. It was very funny.

Gaspard: It's a delightful movie. It was crafted in such a way that at least it seemed to me like you had very cleverly gone, “Well, I can get name people because they're only going to be here for a couple days. It's not a big deal.” You know, “I only need Will Geer for a few days,” if you're shooting it that way. “I only need Ruth Gordon for a couple days. I only need Lloyd Nolan for a couple days.” So, it's kind of fun for them, but it's not a huge commitment.

I think a lot of filmmakers don't think that through when it comes to, you know, you might be able—if you're making a low budget, no budget movie—you might be able to get somebody to come in for very little if they like the script. And if it's only going to take a couple days. If they're going to be sitting around for three weeks, well that's a whole different consideration. But if they can have fun for a couple days, that's just a really smart way to write it, I think.

Badham: Yeah, it was nice. It was easy to get to, because we fly 'em up to Salem, Oregon. I think everybody was from LA. I forget where Ruth Gordon was coming from, but that was not bad. And it's a very pleasant area there in Oregon. The air is just fabulous compared to LA air, especially at that time. And, you know, just really, really pleasant.

Gaspard: Well, if you haven't seen it for a while, it is on YouTube. Give it look. And I think should talk to the producers about getting it out on Blu-ray and you should do a commentary on it. It's just a little lost gem. Okay. Enough on that. We'll move on now to probably my favorite John Badham movie, and that's WarGames. What I was surprised to learn, was that you came into the movie when it was already up and running. Some stuff had already been shot, right?

Badham: Yes. They had shot for maybe a week and a half, I'm guessing.

Gaspard: Okay. And that was Marty Brest who started it and then went away?

Badham: Right. Yes.

Gaspard: Another terrific director, with Midnight Run being one of the best comedies, maybe of all time. So, what do you do in a case like that, when they say, you know, the phone rings and they say, “This movie's up and running. Get up to speed as quick as you can.” What does that mean? How quickly can you get up to speed?

Badham: Well, my agent calls me and says, “There's a picture that they would like you to take over, and I don't think you should do it.” “Why is that?” “Well, it's always when they're in trouble and they have to replace the director, there's, going to be real trouble there in River City, so stay away.”

I said, “But what if it's any good?” And he said, “Well, I don't know.” I said, “Well, I think we should read it.” So, I read it and I said, “This is really wonderful.” And I go in to meet with Paula Weinstein, who was running UA at that time. And after we talked for a while, she said, “When could you start shooting on this?”

And it was about two in the afternoon. I said, “I can walk over there and start shooting right now.” She went, “What?”

I said, “The trouble is, it won't be any good.” She said, “Why not?” I said, “Because I barely read the script. I needed time to, you know, kind of absorb it and get my head wrapped around the thing. I think it's a wonderful script and, and I could do it, but the shots I would be doing would be pretty generic. And that's not what you want. You need something, you know, that is not as dark as Marty was bringing.”

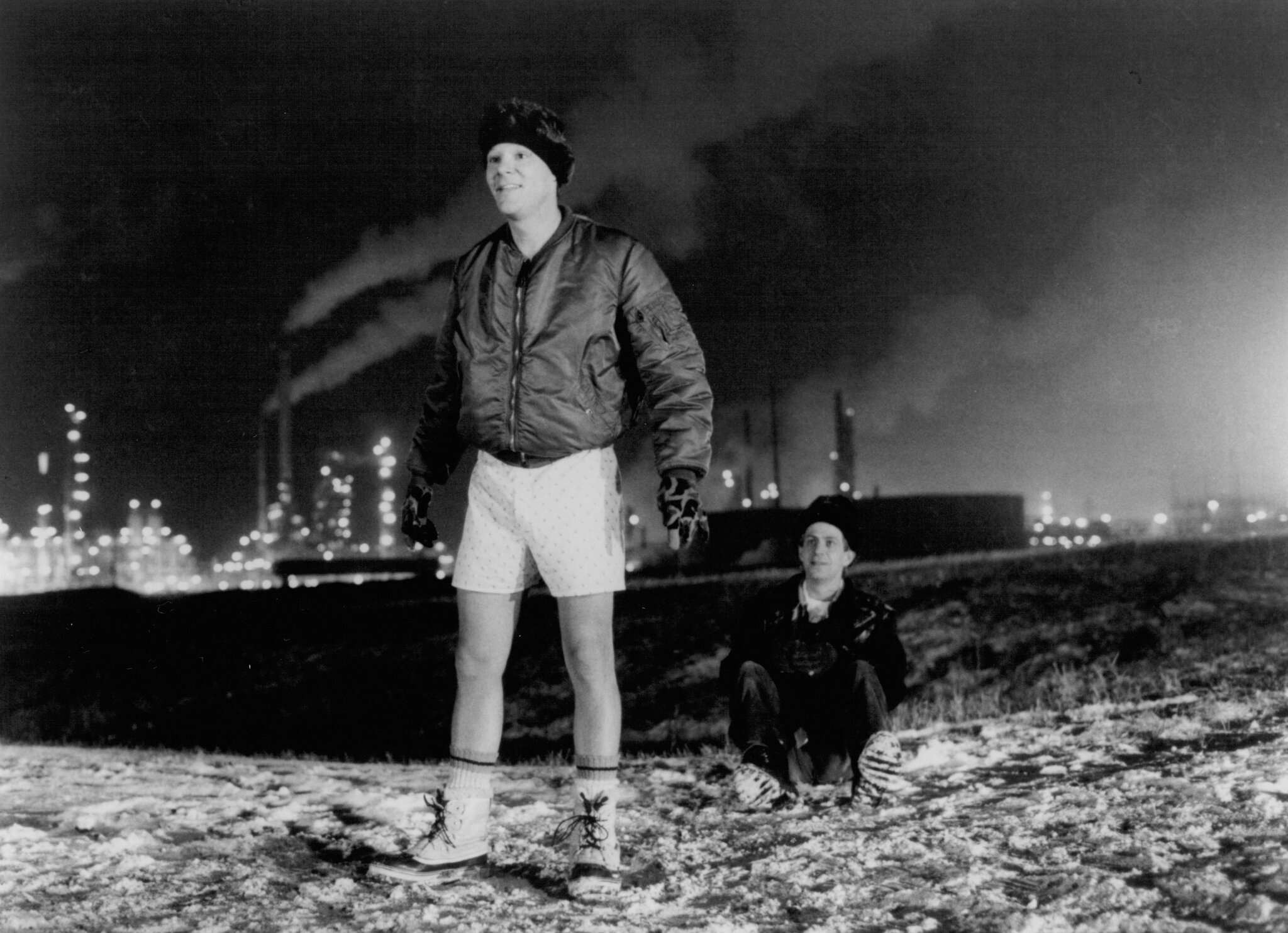

Because I did have a chance to look at the dailies that he had shot and was watching the scene where Matthew Broderick first takes Ally Sheedy up to his bedroom and shows her how he can change her grade on the computer.

And I'm looking at this scene and I'm kind of thinking, “The actors are good. I don't know who these kids are. Photography's wonderful. What's the problem here? Why is it not working?” And then it came to me, they're not having any fun. If I could change a girl's grade on the computer and I was that age of 15, 16, I would be peeing in my pants with excitement, you know? I would not be treating it like we were sixties rebels on the dark web—if there had been such a thing at the time. It's not that at all. It's a kid who's into games and playing. So that was the first thing that I re-shot—I took them right back to that bedroom on the stage.

And it took us, oh my gosh, several takes before we could even get them warmed up. Because Matthew and Ally figured that they were going to get fired any minute too. So, they were terrified of me. And as we kept doing takes, I would just run in there and tell jokes and tickle 'em and do anything to make it, ‘this is light and breezy and we can have fun.’

And so around take 12 or 13—I never do that many takes, but I figured I can't turn in dailies, that look only a little bit better. They've got to be a hundred percent better for the studio to have gone to all this trouble. So, I said to them, I said, “Okay, we're going to have a little break here. We're going to take 10 minutes for coffee. Matthew and Ally, you and I are going to have a race around the outside of the stage, and we'll race around here, and the last person back has to sing a song for the crew.

Gaspard: That was going to be you,

Badham: I knew who that per person was. You know, I'm like 20 years older than them already at that point. I know who's going to lose. And as we get back to the stage, of course I'm last. And I remember this old song that we used to sing in Glee Club in high school called The Happy Wanderer, where a guy yodels. And that just kind of helped break the ice and, loosen them up so that they started to get more playful with it.

Gaspard: How did the bit of business where she traps him between her legs come about? Was that a rehearsal thing? Was that you? Was that them?

Badham: Oh, I think it was something Ally just did. It was very, very erotic in its own little way.

Gaspard: And his reaction is great too. because he doesn't know what to do.

Badham: Yeah. Yeah. That's right. I forgot, totally forgot about that, but I do remember it happening.

Gaspard: You know, if in a parallel universe I'd be interested in seeing what a finished WarGames by Martin Brest would look like, but I'm glad we got your version, because I think that's the one that's more of a crowd pleaser.

By the time you were pulled in, was the NORAD set already designed and built?

Badham: It was. Yeah, pretty much built, they were already shooting tests in there to see how to sell the thing the best. And Billy Fraker, the cinematographer and myself, went over there and spent a lot of time walking around saying, you know, “how would we shoot this?” You know, how was I thinking about shooting it versus whatever Marty had in mind.

Gaspard: Right. Was all the casting done at that point? Was Dabney Coleman already cast and John Wood?

Badham: Dabney Coleman was cast. John Wood. I recast, Matthew's father.

Gaspard: Okay.

Badham: I didn't care for the father they had. And I recast the general, who they had. He was okay, but it needed a bigger personality.

Gaspard: The visuals on the Crystal Palace set on those screens, were those already in production when you came on? Because there's a lot going on on those screens and that's all happening live while you're doing it, right? This is not today. This is back then, and everything that happens happens right in front of the camera. Were those all ready to go when you came on, or were you part of getting that ready? Because there's so much stuff going on in those screens.

Badham: This movie, as far as that concerned, was brilliantly prepared. I mean, they were creating film that would take you several minutes per frame in the optical printer to create. And that had been going on for quite a long time because they had six front projectors, four rear projectors, and 82 video monitors. All of these hundred and whatever had to work in sync with each other, which had never been done before.

Nobody had ever tried to gang that much equipment together to run. And the Hollywood family that did this for years, the Hansards, were able to solve the problem, so you had all these projectors running in sync and you could photograph from any angle which, you know, you maybe might have trouble doing if you were doing blue screen. It used to be with front projection, rear projection, you didn't want to move the camera because you didn't want to get off the hotspot of the arc light. If you got off to the side, it would fade out. But the film had gotten a lot faster. And Fraker was just the best at making all this stuff go together.

Gaspard: The sequence at the end when everything's blowing up, you get so much bang for your editing buck and you're shooting it all live. That's what just kills me. I mean, nowadays they would just, “okay, we'll deal with all that in post.” But you had to go into the edit suite with all those shots of all those screens, doing all those different things for that last big, WOPR explosion thing. For the time, it's really incredible.

Badham: Well, I much prefer it that way. You know, Jim Cameron in the latest film of Avatar, he is managed to get it so what he sees through the camera is what you're going to see on the screen. He is not waiting for stuff to come back from some horrendously tedious project. And so, we are doing a much cruder version of that than what Jim was able to accomplish. But it's, you know exactly what you've got at that time, and you're not suddenly stuck with bad exposures and nasty looking bad blue screen work.

Gaspard: That's the balance that I think is so amazing in your career. Great performances, highly entertaining stories, but my goodness, the action and getting all the pieces you need. Just an education in itself.

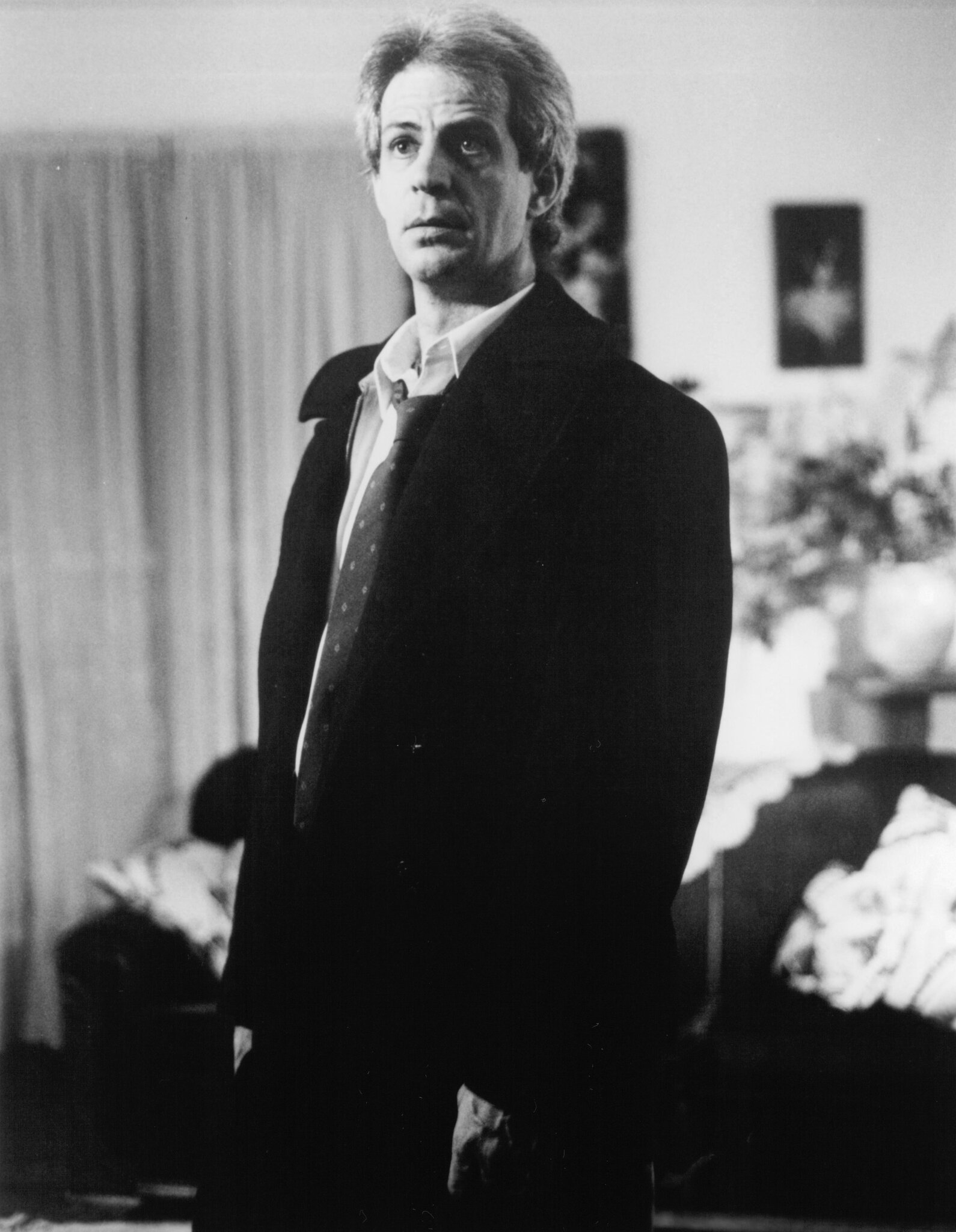

John Wood. I'm a huge fan of John Wood. He wasn't in enough movies. What was it like working with him?

Badham: This was an absolute lovely English pro of the first order. You know, English actors are so disciplined and so together, compared to our American actors who tend to be a little loosey goosey. So, I had somebody who was just totally focused on doing the best job that he possibly could.

And he was so humble, maybe falsely humble. I used to think that. But he would come up and say, “Oh, dear boy, I'm ruining your movie.” And I'd say, “Oh, John, that's bullshit. Just shut up. You're doing great, it's just lovely.”

And he was at that point just starting rehearsal for Amadeus, to play the Salieri part on the road. And he was asking me, he said, “They've got us on a raked stage, for this, which is fine,” he said. “But my back is killing me. I can't be on this raked stage with the high heel shoes of the period.” And I sent him to my chiropractor, in Culver City. And he came down to where they were rehearsing and managed to completely solve his back problem with different kinds of shoes and stuff like that. So, John was just, you know, so, grateful for that, because he was miserable.

Gaspard: In WarGames he is the center of one of my favorite shots of yours in the war room, when he first enters, and he comes down the stairs and crosses the entire room.

Badham: Mm-hmm.

Gaspard: Do you remember how you did that shot?

Badham: Oh yeah. Well, we did it with a crane that was designed to work inside and was one of the first cranes that would extend out and pull back through the space that he was going through.

Gaspard: Was that the Luma Crane?

Badham: Yes, it was, thank you.

Gaspard: I remember that from Polanski's Tenant film. He had it where it snaked up through a stairway, but it's such a lovely shot.

Badham: It did work out really nicely. The war room was stepped up as you went toward the back of it, it went up, you know, four or five steps. So, it wasn't a matter of being able to dolly straight back, because you couldn't do that. But the Luma Crane was better than your average Chapman Crane because it had this extender on it. The mechanics of it were very difficult, however, and it slowed you down to a crawl because it took so long to get it set up, rigged and = right. And now, there's better equipment, so I'm sure nobody except Mr. Luma uses it anymore.

Gaspard: Right, but at, but at the time it was—

Badham: —oh. It's great.

Gaspard: An audience member watching the movie is unconsciously aware of the fact that this room has steps and goes up because you've seen people coming down the steps, going up the steps, even to the stairs on the side. But I mean, the room is just tiered. And so, when you see John Wood come down the stairs, cross the room and go up and up and up and the cameras with him the whole time, you mentally go, “how were they following him? They're going up steps.” And it's not steadycam, because I don't think steadycam came about till maybe—

Badham: Steadycam was around since 74.

Gaspard: Anyway, it's just a fabulous shot. Two more things on WarGames. The opening scene, with the two guys who are in the bunker, is such a great tension scene. It's beautifully staged, but it also sets up the theme of the movie so perfectly. Was that always the opening of the script?

Badham: As long as I worked on it, it was always the opening.

Gaspard: Did you make any changes or go back to previous drafts when you came on board?

Badham: I did. I asked them to send me every draft that they had, and they had taken the original writers Lasker and Parks and had replaced them with a couple of other writers, and they had changed the script quite a bit. And I went back and read Lasker and Parks and said, “this is the one that we need. I'm throwing these other ones out.” And I called the guys up and I said, “Come back. Help me out here. You know, we can tidy up the script the way you like it, the way it should be.” So, we were able to do that and to finetune it to where I think it was doing the right thing or doing the best job.

Gaspard: Okay. One more WarGames question. In the I'll Be In My Trailer book—and in both books—you talk about being totally honest with actors. But you are occasionally willing to keep them in the dark, or I wouldn't say trick them, but not necessarily tell them everything is going to happen, just to see what they do. The example in WarGames is when Matthew Broderick tussles, Dabney Coleman's hair, after his hair has been tussled by Dabney Coleman. And I believe that that was something you told Matthew to do, but you didn't tell Dabney. How often does that come up, and how often should you use that sort of technique of surprising people on camera?

Badham: Well, I think it can be fun. You get a spontaneous reaction from them and if it works, that's great. If not, you've always got what was scripted.

Gaspard: Right.

Badham: And sometimes you just get an idea watching it. For example, the Dabney Coleman/Matthew Broderick example that you give: they had to kind of shake hands or hug or whatever, and in the excitement of it, Dabney rubs Matthew's hair in the rehearsal. And so, I went over and told Matthew on the quiet, “Hey, you do it to him, you know, to surprise him.” Because Dabney has a temper and he kind of reacts and I knew he was not going to just take it lying down. And yet he's like, you know, six or eight inches taller than Matthew. So Whatcha gonna do You gonna hit the kid?

Gaspard: It's a lovely moment. And what I love about that ending of WarGames is that when the movie's over, it ends. You don't drag stuff out, the movie’s over and we're done. I wish more films did that. Is that just a built-in barometer with you that you just know when it's time to just put up The End?

Badham: To get out. I mean, I hate watching movies where you just have one ending after another and you've gotta wrap up every single character. And I understand why people do that, but it just bores me silly. And that's probably coming from working in television where they always have to have—at the end of an episode—an epilogue. You know, we've convicted the murderer, we've gotten the bad guy, you know, and then they go to commercial and they can come back and they have a two minute scene. And usually it's just deadly stuff. There's nothing, much fun about it.

I did a lot of episodes of Supernatural and they had hit on a formula that actually worked great. Which was, you went to commercial, when you came back, you'd always have a scene with the two brothers that was sort of off topic from what the rest of the thing had been. And it was just great fun. And you hung in there to watch it. because it was a delightful addition. It was not some, you know, millstone hung around the series neck.

Gaspard: It's not literally filler where you're trying to fill those two minutes. You've actually come up with something fun. Do you have a couple more minutes? Just talk about Dracula very quickly.

Badham: Yeah. Let's do that.

Gaspard: What a great version of Dracula. I believe in one of the two books, one of the things you said was, “Don't be afraid to say, ‘I don't know, let's figure it out.’” And I got the sense you did that a lot on Dracula. There was a lot of, how do we do this? I don't know, let's figure it out.

And you had some of the best people. One of them I want to ask about is working with Albert Whitlock and matte paintings, which are beautiful in that movie. And, of course, seamless, because his stuff was seamless. I should know how this is done. I don't. Is he painting the painting and you're bringing it live to the location and setting it in front of the camera with the part open that you need for the live thing? Or is that all placed on in post?

Badham: The old-fashioned way to do it is you would set a frame up in front of the camera and, now let's say you were extending a building up, so you would literally stand there and paint it on the spot.

Gaspard: Okay.

Badham: That was the first way that they did it. So that when you shot the film, you had a combined matte painting: it was all together as one piece. Albert, what he did was, he would block off in black all the parts where he's going to paint and just leave open the parts that we're going to photograph and make it so that none of that black part was exposed to anything. He would make you put down a platform that was rigid, it would take an earthquake to move, because nothing could move, everything had to be absolutely stone rigid and you would shoot two or three takes of whatever it was, the castle, Dracula’s castle was one that we did, you know, several of.

And now take that film back to his studio and put it in the refrigerator. Do not develop it. Now he would go in and clip off a few frames from the unexposed negative and develop that. And now create a matte where he painted in everything. And he could now take the original film out of the refrigerator and he would run that through the camera again, not exposing the part that had already been exposed, but now just exposing the top. And so, it was all original negative. That was his whole feeling, that he was not working with dupe negative at all.

Gaspard: That's why it so great.

Badham: And it is absolutely perfect. By that point in England, the guys had kind of tried to go beyond that and figuring—with new film stocks—they could make dupe negatives. Albert only gave us 10 shots, and other ones that we had were done in a newer style, where they didn't have original negative and they don't look as good as what he did.

Gaspard: One last question about actors, because you had a great example in Dracula of dealing with an actor who was sort of playing with you to get more time on camera. And that was Donald Pleasance and his bag of candy. At what point did you realize that he was doing that, and what advice do you give to someone who has an actor who's playing games to be on camera?

Badham: When you realize what's going on, you have to decide how are you going to deal with this? I had a similar situation with James Woods in a movie called The Hard Way, and he's the same kind of same kind of guy. Exactly. Always looking to kind of sneak more time on camera, how to upstage other people.

Donald is the genius at up staging other people. And I would just call him on it and say, “Donald, let's give Lord Olivier his close up here. Let's give Larry his closeup.” I never called him Lord Olivier. If you called Olivier ‘Lord Olivier,’ he’d say “Larry, dear boy. Larry.”

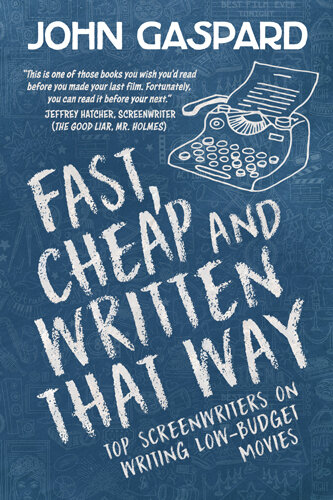

Dying to make a feature? Learn from the pros!

"We never put out an actual textbook for the Corman School of Filmmaking, but if we did, it would be Fast, Cheap and Under Control."

Roger Corman, Producer

★★★★★

It’s like taking a Master Class in moviemaking…all in one book!

Jonathan Demme: The value of cameos

John Sayles: Writing to your resources

Peter Bogdanovich: Long, continuous takes

John Cassavetes: Re-Shoots

Steven Soderbergh: Rehearsals

George Romero: Casting

Kevin Smith: Skipping film school

Jon Favreau: Creating an emotional connection

Richard Linklater: Poverty breeds creativity

David Lynch: Kill your darlings

Ron Howard: Pre-production planning

John Carpenter: Going low-tech

Robert Rodriguez: Sound thinking

And more!

Write Your Screenplay with the Help of Top Screenwriters!

It’s like taking a Master Class in screenwriting … all in one book!

Discover the pitfalls of writing to fit a budget from screenwriters who have successfully navigated these waters already. Learn from their mistakes and improve your script with their expert advice.

"I wish I'd read this book before I made Re-Animator."

Stuart Gordon, Director, Re-Animator, Castle Freak, From Beyond

John Gaspard has directed half a dozen low-budget features, as well as written for TV, movies, novels and the stage.

The book covers (among other topics):

Academy-Award Winner Dan Futterman (“Capote”) on writing real stories

Tom DiCillio (“Living In Oblivion”) on turning a short into a feature

Kasi Lemmons (“Eve’s Bayou”) on writing for a different time period

George Romero (“Martin”) on writing horror on a budget

Rebecca Miller (“Personal Velocity”) on adapting short stories

Stuart Gordon (“Re-Animator”) on adaptations

Academy-Award Nominee Whit Stillman (“Metropolitan”) on cheap ways to make it look expensive

Miranda July (“Me and You and Everyone We Know”) on making your writing spontaneous

Alex Cox (“Repo Man”) on scaling the script to meet a budget

Joan Micklin Silver (“Hester Street”) on writing history on a budget

Bob Clark (“Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things”) on mixing humor and horror

Amy Holden Jones (“Love Letters”) on writing romance on a budget

Henry Jaglom (“Venice/Venice”) on mixing improvisation with scripting

L.M. Kit Carson (“Paris, Texas”) on re-writing while shooting

Academy-Award Winner Kenneth Lonergan (“You Can Count on Me”) on script editing

Roger Nygard (“Suckers”) on mixing genres

This is the book for anyone who’s serious about writing a screenplay that can get produced!