The Making of "Patti Rocks" (An Oral History)

In 1987, the film “Patti Rocks” was produced in Minnesota. In 2004, I chatted with three of the people who instrumental in getting it made: Director and co-writer David Burton Morris; producer, DP and editor Greg Cummins, and actor and co-writer John Jenkins.

Patti Rocks is a sequel of sorts to your earlier film, Loose Ends. How did that first film come about?

DAVID BURTON MORRIS (Director, Co-Writer): I saw Memories of Underdevelopment, a Cuban Film, at the Walker Art Center, and I rushed home to my wife, Victoria, and I said, 'You know, we can make a movie really cheap. I just saw this great movie, it was black and white. If we can scrape together $20,000, we can make a movie.'

And so we did. She wrote it. And it shot for two weeks. Loose Ends was sort of a calling card. We went to 20-25 film festivals, didn't win anything really, but Roger Ebert discovered us and Vincent Canby and Andrew Sarris and we got all these great notices.

However, it was nearly twelve years before the sequel, right?

MORRIS: We finally got enough money, in the early 80s, to do a movie called Purple Haze, and that did very well. It won Sundance, and that was our first real movie. It was 35mm, color, we had an actual shooting schedule and a budget. And that did very well. And we looked like we were on our way.

I then, subsequently, got fired from two studio pictures and was very unhappy—we're now talking mid-80s—and I was thinking about quitting, I was thinking about getting out of the business because I was really unhappy. And I thought back to the only time I had a really good time making a movie, which was on my first film, Loose Ends. And I thought, maybe I should think about writing something for those guys and making it back in Minnesota and sort of re-creating my enthusiasm for making movies.

Hence the title in the credits, '12 years later.' A lot of people don't get that, but when it screened at Sundance they showed them both, which was nice, so that people could watch the first one and then pick up with the same two guys 12 years later.

CUMMINS (Producer, DP, Editor): When Patti Rocks came about, David had moved to Los Angeles and was working out there, doing the Hollywood thing, and he met Gwen Field. Gwen was taking her daughter to the same day care that David was taking his daughter to, and they got to know each other, and David pitched the idea of Patti Rocks to her.

How did the script come together? I know you started with improvisations …

MORRIS: We did a lot of just riffs on sex. We had another movie in mind. And I had all these long cassette tapes filled with (Chris) Mulkey and (John) Jenkins riffing on women, and I thought, this is interesting. Somehow I got the idea of putting them in the car, driving all night to see Patti to talk her into having an abortion. I did a first draft and I'd give it to them and we'd tinker with it and do some more improvs. Jenkins lived in Chicago, so we flew there a couple times and did some more improvs, and then I'd type that up.

JOHN JENKINS (Actor, Co-Writer): It started with some general conversations about what we might do, and then we started to improv a little bit. David then took that and began to craft a plotline for this.

Then after we had that in place, we got back together again and we spent some more time improvising the script. And so the script really came out of those improvisations that Chris and Karen (Landry) and I did.

Then David would edit that and cut and paste and re-arrange. He might add some other dialogue on top of that, but most of it came out of those improvs.

Where did the title come from?

MORRIS: The way I got the title was interesting. I was at the Chicago Film Festival, on a panel. I was at dinner with a group of people from the festival and this woman was sitting next to me. I said, 'What do you do?' She said, 'I sing in a band.' I said, 'What's the name of the band?' She said, 'Patti Rocks.'

And I said, 'Oh, that's a really good title.'

How did you get the film financed?

MORRIS: I'd known Sam Grogg, because he was head of the USA Film Festival in Dallas. And he'd started a film company called Film Dallas. So I gave him the script and said, 'What do you think?' He said, 'We'll make it.'

It was the easiest thing I've ever done. I wrote it and within a month they'd given me $400,000 to make this movie.

He had very few notes. He just said, 'They have to get out of the car midway through the movie.' I said, 'What do you want them to do? See a flying saucer?' He said, 'I don't know, you'll think of something.'

Did the script change much besides that before you shot?

MORRIS: My wife, Victoria, helped a lot on the third act. She said, 'The Patti character has got to be a strong, liberated, likeable woman.' So I took those notes and did a re-write on it, and Karen Landry brought a lot of insight into the character.

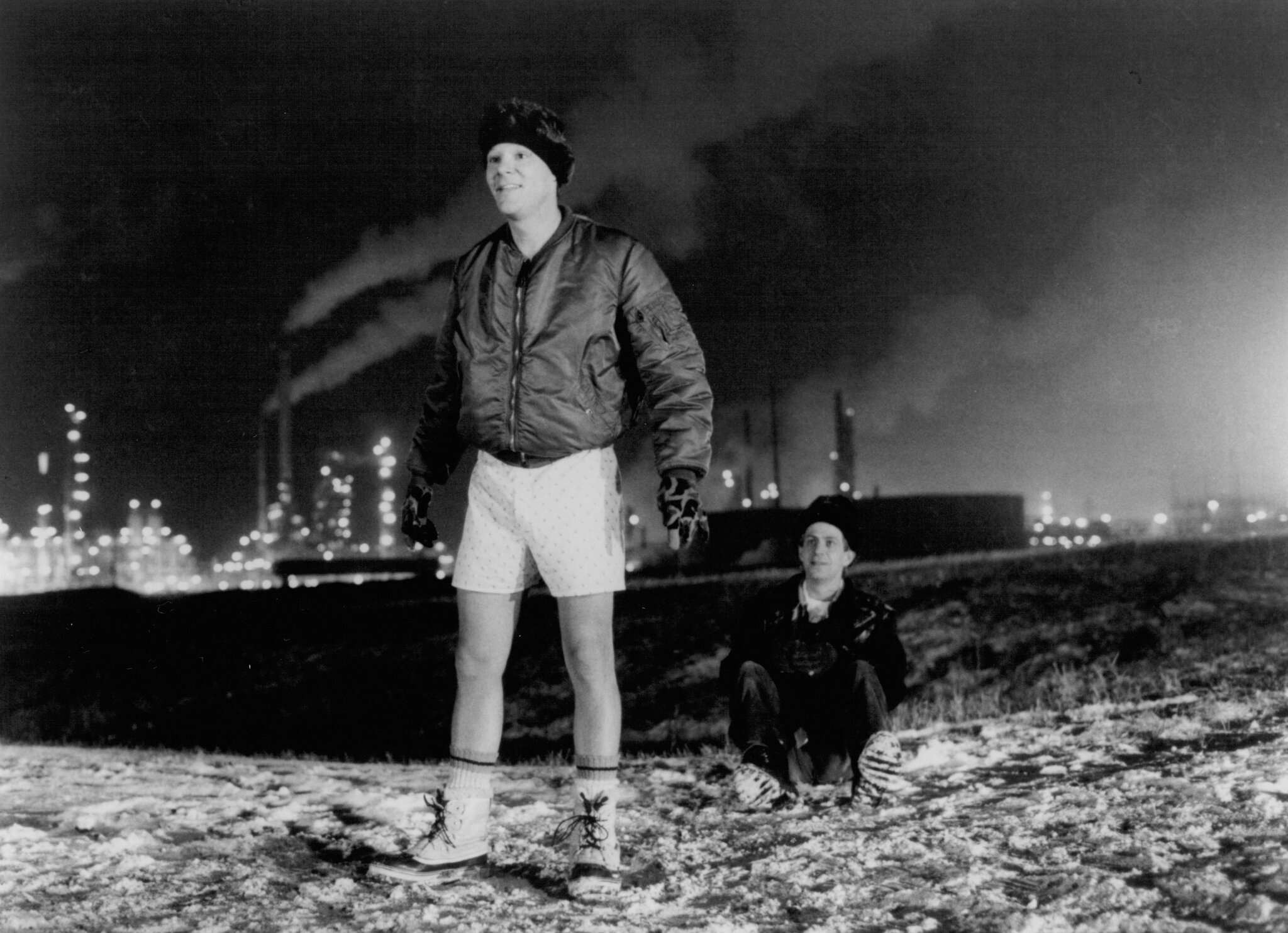

I wrote it for the summer, because Mulkey's running around in his underwear. But we couldn't get it all together, and we got the money in November, and I said, 'We're going to make the movie. We've got the money, we're going.'

And it actually turned into a more interesting film, just because of the look of the snow and Mulkey running around in his underwear in 23 degrees below zero.

I thought, two guys in a car? How expensive can that be? But, because of the cold, it was brutal. I mean, it was just really brutal—cameras freezing and all of us crammed in, in snow parkas, in the back seat, shooting at night in the middle of the winter. It was insane.

CUMMINS: In theory, David was right, it was a very simple idea: two guys in a car. But add in the car, add in winter, add in nights …

One of the great things in the movie is how you capture just how cold a Minnesota winter can be. You can really feel it while watching the movie.

JENKINS: The weather was unbelievable, especially when we were shooting the sequence where they get out of the car. It must have been thirty below when we were shooting that scene.

CUMMINS: We shot Loose Ends in the summer, in July, and it was one of those horribly hot summers. Basically, it was heat and sweat and working really hard and rigging lights in Midway Chevy’s repair department when it was 100 degrees out.

And then we turned to Patti Rocks and it's just the opposite. We were shooting in December, and it was the coldest December on record. We were on the camera car with 60 degree below zero wind chills.

JENKINS: We were in this trailer and we would come out; we could only shoot this stuff for four or five minutes at a time before the fear of frostbite or hypothermia would come up. Chris was in great shape and even at that it was brutal. When it came to looking cold, no sensory work was required.

CUMMINS: The camera got so cold most of the time that it was squeaking. When it dropped below 20 below, the camera ran fine but there was this high-pitched squeak every few seconds. We couldn't figure out what it was for the life of us. It would go away when we'd take the camera into the trailer, and then we'd go back to the car and it would do it again. It was just the cold.

MORRIS: The lesson from Patti Rocks was, when you get the money, make the movie, regardless of what season it is.

The film is a three-hander, but we spend so much time in the car that it also feels like a character in the story.

CUMMINS: While scouting locations, there was a car for sale. So, we stopped right there and bought the car—it was for sale on the side of the road. Without thinking about anything. How would this car rig, what does it sound like? It was the perfect car for the character, but not the perfect car to shoot in.

It was a two-door. We loaded the camera in the car, we had David and myself and the sound man all rammed in the backseat, depending on where we would rig the camera for the shot. It was long before video assist, so we had to be in the car, seeing what was going on, in order to see the performance.

Did you ever consider just using process shots, instead of shooting while driving?

CUMMINS: I didn't want to do process, I felt it would cheapen the film to do process all the time. But I don't think any of us really realized how difficult all the shots were going to be.

Before we shot the film, we knew that the car was a character in the film. The car was as important, in some ways, as Billy and Eddie. And so we planned out a myriad of placements for the camera—we could put the camera here on the front of the hood, to the right of the hood, to the left of the hood, and so on.

And then what I did was work through that process from the beginning of the film through the end. None of the camera placements really repeat. They move and they evolve. And so the car changes with each story they tell, and it becomes more intimate. And it becomes really intimate before they arrive at Patti's apartment.

We worked very hard to keep that part of the cinematography alive. It was very hard to do, and very confusing. We shot a lot of stuff that didn't get into the film, stories that didn't quite work as well as other stuff. Keeping track of camera placement became very complex, especially with a small crew. We had one person on continuity, who basically couldn't be in the car. How do they do their job? It's a big challenge, so continuity fell to David and myself, really.

Shooting in a car, a black car, with black upholstery, in the middle of nowhere, in the middle of the night, with minimal equipment, in the cold, was brutal. Absolutely brutal.

So not only were you shooting in the cold, in a car not designed for shooting, but you were also shooting at night …

CUMMINS: It was a road film, but when we started out, we didn't know it was going to be a nighttime road film. Which made it even more difficult.

We wanted to play it almost real time—they left in the afternoon, they got together, they had a couple of beers and they took off and night fell. In the winter, night falls around here at about 4:30 in the afternoon. And so they drove all night to get to her apartment, and they get there sometime in the middle of the night and leave the next day at dawn—it's all in one day.

Life would have been easier if they'd started with breakfast, then driven down and gotten there about four in the afternoon—that would have been wonderful.

From an acting technique point of view, how did you recreate what you had done in the improvisations while shooting?

JENKINS: It's an interesting problem, to use improv to create a script, and then to go back and play it. It's a funny thing. When you're improvising the thing, you're so involved in the problem and the words just flow out.

But when you go back to do it again, you've forgotten a lot of that structure or the dynamic that allowed those words to flow. So you're left with a script and you know it's yours, but it's hollowed out. You've forgotten the context a little bit.

It's almost easier to take somebody else's words and to slip on your imagination and work with that, then to go back and do your own stuff. I found that to be a little difficult.

I had to do all the actorly stuff and fill it out, sensory work and subtext to try to get back to that improv state that had been so easy. It was just odd. You would think that it would just be a piece of cake, the easiest thing to do, and I found it perplexingly difficult.

The film became somewhat controversial, due to its language. Were you aware that might be an issue while you were shooting?

CUMMINS: Oh, absolutely. We set out to do that.

The thinking was, these are two guys and this is the way guys talk. If you put two kind of raunchy guys together, this is how they talk. There's nothing unreal about this. And essentially that's what we wanted to do: present two guys who are completely uninhibited and unobserved, talking in the way that we felt some people do. Sam Grogg felt the language was its strong point, that's what the film was about.

MORRIS: I thought it was risky, in terms of the subject matter. I didn't know until after it was done how people would react to the language in the picture. The ratings board first gave us an X for language, and that had never happened before. I guess I was just so used to it. Not that I talk that way, but certainly I hear that. I was kind of surprised by the reaction.

JENKINS: I didn't think it would be controversial. It wasn't violent, there wasn't any hard porn. It's odd about it now, but we got in trouble for the language. You listen to HBO, and you listen to something like Deadwood, and it seems odd to me. But that was a vastly different time, in terms of what kind of language you could use in a film.

MORRIS: When I first started putting this together, I thought people are either going to love or hate this. I had no idea it was going to divide audiences. And it did. People loved the movie or hated the movie. More people loved it, thank god, than hated it.

JENKINS: That was just the way we talked, but in an exaggerated way. It seemed appropriate to these two guys and the way they would talk. It felt true to us.

MORRIS: At the very few personal appearances I made before the movie, I'd say, 'Some of you people might get uncomfortable during the first two acts of this movie. Just wait, okay?'

CUMMINS: When we screened the answer print for the first time, in California, all of a sudden Sam Grogg, who was with FilmDallas, brought five or six people into the screening room. He wanted them to see it, but we hadn't even seen the film yet. But we really couldn't turn him down, so we watched the film, and afterwards Sam says to them, 'See what you can do for a half a buck?' They were his next round of directors, and he was pressuring them to keep their budgets low.

MORRIS: We had a lot of screenings in Los Angeles before it opened up, and it was sort of a word-of-mouth hit, as far as people going to these screenings. Sean Penn, Madonna were there. I just hate watching my films with audiences. It makes me uncomfortable. So I never went to these screenings.

In addition to the language, the film also includes a sex scene. How was that handled?

JENKINS: It was difficult to do. I'm doing a love scene with my best friend's wife—my real best friend's wife. It was potentially explosive. I thought we handled that part of it well. We got to the point where both Karen and I felt comfortable to do the scene. I thought we were able to finesse it all right.

CUMMINS: There was a level of trust in the sex scene. This is Chris's wife, who's making love with John Jenkins. This is a difficult scene. It's difficult to have your wife in a nude scene, it's difficult to be in the same film with your wife in a nude scene, it's difficult to have your wife making love to your friend as a character, but he's a real-life friend.

We created a lot of really difficult situations that we were able to get through because of that trust that we had with each other.

What did you learn while making Patti Rocks that you still use today?

JENKINS: Work with people that you know and trust. I know that's hard to do. A lot of this work is going to be like blind dates with strangers to put these things together. I was fortunate to be able to work with people I loved and trusted. If possible, for your first steps out, to do it in a way that you were protected in that way would be great. Look for that.

CUMMINS: One of the best decisions I made as producer was insisting upon getting the best people, friends who were really capable, and to stand up for them.

Film is a collaborative art, there's no question. Everybody says that. You can't really do it by yourself, you really need other people, other expertise, other views, other opinions. You need people in the process. And the closer you are to those people, the less explaining you have to do, the more intuitive working relationship you can have, the faster you're going to be able to work, the better off you're going to be.

The most important thing that I say to everybody is that you have to listen. You have to listen to other people, because they're telling you something.

Everybody really has something to give, and it seems like too often we're not listening to those voices.

If you can sit and hear people, and be quiet, I think you'll learn a lot. You take in a lot just by being there, rather than trying to dominate everything.

Dying to make a feature? Learn from the pros!

"We never put out an actual textbook for the Corman School of Filmmaking, but if we did, it would be Fast, Cheap and Under Control."

Roger Corman, Producer

★★★★★

It’s like taking a Master Class in moviemaking…all in one book!

Jonathan Demme: The value of cameos

John Sayles: Writing to your resources

Peter Bogdanovich: Long, continuous takes

John Cassavetes: Re-Shoots

Steven Soderbergh: Rehearsals

George Romero: Casting

Kevin Smith: Skipping film school

Jon Favreau: Creating an emotional connection

Richard Linklater: Poverty breeds creativity

David Lynch: Kill your darlings

Ron Howard: Pre-production planning

John Carpenter: Going low-tech

Robert Rodriguez: Sound thinking

And more!

Write Your Screenplay with the Help of Top Screenwriters!

It’s like taking a Master Class in screenwriting … all in one book!

Discover the pitfalls of writing to fit a budget from screenwriters who have successfully navigated these waters already. Learn from their mistakes and improve your script with their expert advice.

"I wish I'd read this book before I made Re-Animator."

Stuart Gordon, Director, Re-Animator, Castle Freak, From Beyond

John Gaspard has directed half a dozen low-budget features, as well as written for TV, movies, novels and the stage.

The book covers (among other topics):

Academy-Award Winner Dan Futterman (“Capote”) on writing real stories

Tom DiCillio (“Living In Oblivion”) on turning a short into a feature

Kasi Lemmons (“Eve’s Bayou”) on writing for a different time period

George Romero (“Martin”) on writing horror on a budget

Rebecca Miller (“Personal Velocity”) on adapting short stories

Stuart Gordon (“Re-Animator”) on adaptations

Academy-Award Nominee Whit Stillman (“Metropolitan”) on cheap ways to make it look expensive

Miranda July (“Me and You and Everyone We Know”) on making your writing spontaneous

Alex Cox (“Repo Man”) on scaling the script to meet a budget

Joan Micklin Silver (“Hester Street”) on writing history on a budget

Bob Clark (“Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things”) on mixing humor and horror

Amy Holden Jones (“Love Letters”) on writing romance on a budget

Henry Jaglom (“Venice/Venice”) on mixing improvisation with scripting

L.M. Kit Carson (“Paris, Texas”) on re-writing while shooting

Academy-Award Winner Kenneth Lonergan (“You Can Count on Me”) on script editing

Roger Nygard (“Suckers”) on mixing genres

This is the book for anyone who’s serious about writing a screenplay that can get produced!

Dan Futterman on “Capote”

Although it ended up becoming an Oscar-winning film, Capote started out the way many independent films do: Someone gets an idea, writes a script, and then gathers his/her friends together to make a movie.

First-time screenwriter Dan Futterman started that traditional process with a couple of distinct advantages: He chose a compelling subject matter (Truman Capote’s relationship with murderer Perry Smith while writing his classic In Cold Blood) and the friends he gathered to make the movie included his talented long-time pals director Bennett Miller and actor Philip Seymour Hoffman.

Where did the idea to write Capote come from?

DAN: I got interested in Truman Capote in sort of an oblique way, and it was almost incidental that it ended up being specifically about Truman Capote.

There was a book that my Mom, who's a shrink, gave me called The Journalist and The Murderer, by Janet Malcolm. It's about a case in California where a doctor named Jeffrey MacDonald was eventually convicted of killing his wife and children. Joe McGinniss was writing a book about him and eventually, when the book came out -- it was called Fatal Vision -- Jeffrey MacDonald sued Joe McGinniss for fraud and breach of contract.

Malcolm’s book is sort of a meditation on how could this happen? How could a convicted triple murderer sue the writer who's writing about his life? How could he convince himself that the writer was going to write something good about him? It dealt with the fact that the journalist is posing as a friend to get the subject to talk, and that the subject has hopes that he's going to be portrayed in a good light, and that the journalist is always playing off of that desire. The relationship is premised on a basic lie that's it's a natural relationship. It's not. It's a transactional relationship.

That seemed interesting to me, and had there not been a TV movie made about that incident, I might have written about that.

Some years later I picked it up again and read it -- it's a pretty short book and I recommend it -- and just on the heals of reading that I read Gerald Clarke's biography of Capote, called Capote, and there are two or three chapters that deal with the period in his life where he was writing In Cold Blood and his relationship with Perry Smith.

I wanted to write about that kind of relationship and deal with those kinds of questions. The fact that it was Truman Capote was an extremely lucky accident, because he's fascinating in so many ways and he's so verbal and also was a man who was struggling with some real demons, I think. That made the work I was doing that much more interesting and deeper.

Up until that point, you’d made your living as an actor. Where did the impulse to tackle a screenplay come from?

DAN: I'd written, as you do, bad poetry in high school and college. And I had written a short story or two. I'd always admired playwrights and screenwriters; it seemed to me like a real trick to get a story told primarily through dialogue.

I thought about writing this as a play, initially, and then for some reason a screenplay felt more liberating. The play, I think, would have felt a little bit closed down and would really center too much on the discussions in the jail cell.

I always thought I wanted to write a screenplay, but I never wanted to do it just theoretically. I wanted to do it with a specific idea in mind that would really become something of an obsession, which is what this became. I almost felt like I would have been terribly disappointed with myself had I not done it. And feeling like I had to write this, or had to try to write this, was not a feeling I'd had before.

You had the distinct advantage, as a beginning writer, of being married to a working writer. How did she help you in this process?

DAN: Although it doesn't seem like there's a lot of plot in the movie -- it's about a guy writing a book about an event that already happened -- but it is quite plotty when you get down to it. And she was clear and strict with me, saying "If there are any scenes where people are just talking about something that you think is going to be interesting, cut it, because if it's not moving the plot forward it doesn't belong in the script." That was important to learn. And it was something that I had never considered.

I did an outline, somewhere between twenty and twenty-five pages with a paragraph for each scene, with dialogue suggestions. The script came out probably 80% tied to that outline.

Did you change the script after showing it to people?

DAN: Not right at the beginning. It kind of was what it was. It was long, almost 130 pages, a lot of dialogue, but you got a very strong sense of what the movie might be from it.

We let it sit for a while. I know Bennett did a lot of thinking about it, as did Phil. And when we finally were getting to the point where it looked like we were actually going to get some financing for this, we got to work.

Did you take any classes or read any books on screenwriting before you sat down and wrote the outline?

DAN: No, I didn't take any classes. I read the Robert McKee book (Story: Substance, Structure, Style and The Principles of Screenwriting) that I guess everybody reads, and I found that pretty helpful ---his clarity about story. I think that was an important lesson for me to learn over and over again, that story is primary. Clever dialogue is not what it's about. It's got to ride on the story, and then you can hang stuff off of that.

Then it was just a matter of trial and error. And the lucky fact of having a subject who has been quoted as having said a lot of funny things, of which I put as many as possible into the screenplay.

What were the upside and the downside of writing about a real person?

DAN: I always hated that moment in school when the teacher, I think inevitably a somewhat lazy teacher, would give the assignment, "Write a story about whatever you want," and I would just panic. My mind would just be a complete blank. But if I got a very specific assignment to write "Why does this character have to confront this thing in this story in Chapter Three," then I was off and running.

Rules are good for me. In that way, I think writing about a real person, knowing basically what the rules are -- you can take a little bit of license, but try to stick to the facts as much as humanly possible -- that felt liberating to me. It has a way of focusing my imagination, I guess, instead of feeling like anything goes and then I'm screwed.

I recently have had correspondence with Wallace Shawn, who is William Shawn's son. He and his brother are not terribly happy about the way William Shawn is portrayed in the film.

I knew that Capote had three different editors involved in the book. One was William Shawn of The New Yorker, one was Bennett Cerf at Random House, and then when Cerf retired, a guy named Joe Fox took over. That just seemed too confusing to present in a movie. We needed one editor and I choose that to be William Shawn, and he would do everything that all the other guys did as well. That upset Wallace and I feel badly about it. If I were able to go back, I would try to solve it.

What you encounter is that, even if the people have died, there is a moral debt owed to them in terms of trying to adhere as strictly as possible to the truth. It's something I tried to be very conscious of, but in this particular case, I think I came up short.

Did you ever consider just fictionalizing the character's name, since he was already a composite of three people?

DAN: It didn't occur to me at the time that any of the things I had him doing could possibly be upsetting to anybody, but that was my own take and I see now why his sons are upset. Looking back now, I would try to find a way to fix it.

Did you do any readings or workshop the script?

DAN: We did a table reading in New York with Phil and some actor friends of ours, just a few weeks before rehearsals started. The reading highlighted the problems that we had been kind of skating over, scenes where we thought, "Oh, I'll fix it later." It focused our minds on actually fixing the problems.

Did you have much rehearsal?

DAN: We had a decent amount of rehearsal and I loved it. It was a terrific experience.

Bennett and I had an important talk about how, mechanically, we were going to run rehearsals. The decision was that he, because he was directing the movie, he needed to develop rapport, relationship, trust with the actors without me around.

We were all up in Winnipeg and in the morning I would go sit with whomever was going to rehearse that day with Bennett and they would read through the scenes. We'd talk about any questions, and then I'd take off and go up to this little room I had and do re-writing from the day before that needed to be done, tweaks, whatever. Then I'd come back at the end of the day and we'd read it again. I think it worked enormously well. I think the actors came to really trust Bennett and it was just a better use of my time instead of just sitting and poking my nose into rehearsals, which would only have been disruptive.

Did any significant changes take place in editing?

DAN: There was a lot of streamlining of the movie.

The first version that I saw was probably 20 minutes longer than the finished version. I'd never been through the process of seeing a movie that was so fat in that way. Bennett was feeling quite good about it and I think he could see where the target was. At that point I couldn't and it felt fat, it felt not terribly funny, sluggish, and I got kind of terrified at that point.

It was just through months of carving it and carving it and carving it that it got to the place where it didn’t have anything extra in it -- and it only got to that place after a laborious process. Bennett and Chris Tellefsen, the editor, knew where they were headed, but it was a little bit difficult for me to see, so to my mind that transformation was enormous, although I don't think it was a tremendous surprise to them.

I saw, finally, a version that I felt really happy with. There was no sound work done on it, there were a couple of little things that needed to be fixed, and I thought, "I'm going to stop watching it now and I'm going to wait to see it all the way through with everything set, color-corrected and all the sound work done." I did that at the Telluride Film Festival, where it was properly projected and there was an audience, and that was a pretty thrilling moment.

What's the best advice you're ever received about writing?

DAN: I think it's got to be what I learned from my wife, that it's all about plot. It has got to move. You have to move through the scenes from one to the other. It's got to feel inexorable that this scene follows upon that scene.

There's no point to moving around capriciously. You're only going to get lost and you're going to lose the audience. As many screenplays as I may write, I don't think I'll change my point of view about that.

What was the experience like to be nominated for an Academy Award?

DAN: I hope this doesn't come out the wrong way, but because the season is so long -- we'd been to Telluride, Toronto and the New York Film Festivals, and then we opened -- and the movie had gotten a great deal of good response, even before it opened, so we knew we had something that people were responding to.

And then sometime in January they announce what's going to be nominated, and by that point you've been through so many different awards announcements -- the critics’ awards that have been handed out or nominees have been announced, Independent Spirit awards nominees were announced by then -- there starts to be a little list that people are saying, "These are the contenders."

Unfortunately, it kind of ruins the experience, because I think that you start to develop expectations, because people are saying, "Oh, look, it's a real possibility," while all along you've been thinking, "Oh, come on, don't be ridiculous." It can't help but eat at you and so you think, "Well, that would be great, wouldn't it?" The fear of being disappointed almost replaces what should be simply shock and elation. And that's unfortunate.

However, having said that, the biggest reaction I had was looking at the list of people I'd been nominated with. I'd never understood before when people said that something like that could be humbling, but, at that point, I got it. And it was largely because Tony Kushner's name was on it, someone whose play I had been in -- Angels In America -- and someone whom I've admired for as long as I've been aware of his writing. To be included in a list with him was simply incredible.

So I had all those emotions at the same time.

It's a heady time, it’s fun. There was no expectation on my part that I would win, because Brokeback Mountain was such a big event. Larry McMurty and Diana Ossana wrote a great script and I think people felt that he was due and the script was great. So it was kind of a fun way to go into the Oscar season, which was that I had no expectations of winning but I was just going to enjoy it.

Any advice to someone starting a low-budget script?

DAN: I know that the premise of this book is about writing stuff that will fit into a certain budget, but I don't know that I would give that advice off the bat. I mean, look, obviously if you're writing scenes where spaceships get blown up, you know where you are. If you're even slightly aware that big things cost money, then you're not going to write things like that.

But to be thinking in that way, I feel, can also get you thinking like, "Well, how will critics respond to this? How will producers respond to this? How will ...?" And you cannot have that in your head while you're writing. You simply have to be thinking, "Do I like this? Do I believe it? Is it interesting to me? When I go back and read it, if I can be as objective as possible, is it exciting to me to read?"

If you're honest with yourself and have some sort of decent barometer for how things are playing, then you can't help but have the right reaction to it. That's the most important thing, to write something that is successful on the page. That sort of second-guessing, I think, is going to be defeatist.

You already have enough voices in your head – and the superego perched on your shoulder, saying, "That's terrible, that's not good enough" -- so the fewer voices you can add to that chorus, the better.

Dying to make a feature? Learn from the pros!

"We never put out an actual textbook for the Corman School of Filmmaking, but if we did, it would be Fast, Cheap and Under Control."

Roger Corman, Producer

★★★★★

It’s like taking a Master Class in moviemaking…all in one book!

Jonathan Demme: The value of cameos

John Sayles: Writing to your resources

Peter Bogdanovich: Long, continuous takes

John Cassavetes: Re-Shoots

Steven Soderbergh: Rehearsals

George Romero: Casting

Kevin Smith: Skipping film school

Jon Favreau: Creating an emotional connection

Richard Linklater: Poverty breeds creativity

David Lynch: Kill your darlings

Ron Howard: Pre-production planning

John Carpenter: Going low-tech

Robert Rodriguez: Sound thinking

And more!

Write Your Screenplay with the Help of Top Screenwriters!

It’s like taking a Master Class in screenwriting … all in one book!

Discover the pitfalls of writing to fit a budget from screenwriters who have successfully navigated these waters already. Learn from their mistakes and improve your script with their expert advice.

"I wish I'd read this book before I made Re-Animator."

Stuart Gordon, Director, Re-Animator, Castle Freak, From Beyond

John Gaspard has directed half a dozen low-budget features, as well as written for TV, movies, novels and the stage.

The book covers (among other topics):

Academy-Award Winner Dan Futterman (“Capote”) on writing real stories

Tom DiCillio (“Living In Oblivion”) on turning a short into a feature

Kasi Lemmons (“Eve’s Bayou”) on writing for a different time period

George Romero (“Martin”) on writing horror on a budget

Rebecca Miller (“Personal Velocity”) on adapting short stories

Stuart Gordon (“Re-Animator”) on adaptations

Academy-Award Nominee Whit Stillman (“Metropolitan”) on cheap ways to make it look expensive

Miranda July (“Me and You and Everyone We Know”) on making your writing spontaneous

Alex Cox (“Repo Man”) on scaling the script to meet a budget

Joan Micklin Silver (“Hester Street”) on writing history on a budget

Bob Clark (“Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things”) on mixing humor and horror

Amy Holden Jones (“Love Letters”) on writing romance on a budget

Henry Jaglom (“Venice/Venice”) on mixing improvisation with scripting

L.M. Kit Carson (“Paris, Texas”) on re-writing while shooting

Academy-Award Winner Kenneth Lonergan (“You Can Count on Me”) on script editing

Roger Nygard (“Suckers”) on mixing genres

This is the book for anyone who’s serious about writing a screenplay that can get produced!

John McNaughton on writing & directing "Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer"

The phrase “not for the squeamish” may well have been invented for John McNaughton’s Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer. Although you’ll find it in the “horror” film section of the video store, it’s far more than a simple horror film. The film is a starkly realistic, almost documentary-style fictionalized look at a few days in the life of confessed serial killer Henry Lee Lucas.

McNaughton, who went on to direct in a number of different genres including the comic-drama Mad Dog and Glory starring Robert De Niro, Bill Murray, and Uma Thurman, drew on his roots producing documentaries to construct the film. But as he admits, it was co-writer Richard Fire’s keen understanding and use of the basics of dramatic construction that helped to make Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer the milestone that it has become.

What was going on in your life and career before Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer came along?

I had a long-standing dream of wanting to make a feature film, but I'd had to put that on hold because, being that I lived in Chicago and was not connected in any way to the mainstream industry, I really didn't know how I was ever going to achieve that dream.

I was working on these small documentary projects that were being distributed by a company in the South suburbs of Chicago, called MPI. I had worked in the commercial field in Chicago, but the first time I was ever on a feature film set I was the director.

Where did the idea for the story come from?

I had done this series of documentaries for MPI, called Dealers in Death, which were about American gangsters, primarily from the Prohibition era. We had scoured the archives for a lot of public domain photographs and footage, got Broderick Crawford to narrate it for us and made a little money on that project.

I was going to produce and direct another documentary piece, based on professional wrestling, because I'd found someone who had a collection of wrestling footage from the 1950s and 1960s with Bobo Brazil and Killer Kowalski and Dick the Bruiser and Andre the Giant, from the period of wrestling before the WWF or the WWE.

MPI was owned by two brothers, Waleed and Malik Ali. I went out to meet Waleed to talk about doing these wrestling documentaries. When I got to their offices Waleed informed me that he had contacted the person who had the footage for sale. The person with the footage had quoted a price and when the Ali brothers approached him, saying, "Okay, we'll negotiate on that price," the guy realized that the brothers had money so he increased his price. The Ali brothers were not to be dealt with in that manner, so Waleed informed me, "Listen, we're not going to do business with this guy. He's a crook."

Early on in the video business -- and the brothers got in at the beginning -- the major studios weren't interested in video rights, because there just wasn't enough money involved. So they were selling off the rights to their films. A couple of companies, like Vestron and Pyramid, became wealthy for a short period of time, until the studios saw the potential in the video market and started creating their own video divisions. And then those companies went out of business.

But in the early days of video you could buy the video rights quite cheaply for low-budget horror films and since a lot of "B" horror titles hadn't been seen widely, they were very successful on video. A "B" schlock horror film that people may not have been interested in going to the theater to see, they were more than happy to rent because they're a lot of fun.

So what was happening at this time was that those titles were becoming so popular that the rights acquisitions were becoming more and more expensive. And so Waleed had determined that it would make sense for them to fund a horror film and thereby own all rights in perpetuity, rather than just buying the video rights for a limited period of time. So he proposed to me that we should join forces and make a horror film.

I went in thinking I was going to be doing these documentaries and instead, it was the day that my dream came true, completely unexpectedly. I was kind of in shock.

Down the hall was the office of an old friend of mine who I had grown up with, Gus Kavooras. Gus was always a collector of the strange and the arcane and the weird. I stopped in to see him and I was kind of in shock. I said, "Gus, Waleed just offered me $100,000 to make a horror movie. I have no idea what my subject will be." And he said, "Here, look at this."

He took a videocassette off the shelf and popped it in the machine. It was a segment from the news magazine show, 20/20, and the segment was on Henry Lee Lucas and Ottis Elwood Toole, who were serial killers. The term "serial killer" was coined in 1983 by the FBI. In 1986 I had never heard the term before and this was something new to me, the idea that there were these random murderers going around.

Most murders are committed by people previously acquainted to the victim. Husband kill wives, wives kill husbands, husbands kill wives' lovers, wives kill husbands' lovers. Most murderers are committed by people who are known by the victim. But this was a new trend in murder where there were these individuals who were just randomly murdering strangers. It was, indeed, very horrifying. There were some interviews with Henry and a lot of photographs. He was really a creepy character. And so that became the germ for the story.

Was the budget an issue while you developed the story?

The budget was written in stone. That was the mandate from Waleed, "Make me a horror film for $100,000." So the budget was always a consideration.

How did you and co-writer Richard Fire work together?

I put together a set of 3x5 index cards delineating a scene structure, but I was not an experienced dramatist, screenwriter or otherwise. But I had the money, I had the mandate to make the picture, and we had our subject: the true story of Henry Lee Lucas.

I had a friend, Steve Jones, and he was working as a director of animated commercials in Chicago, primarily doing Captain Crunch commercials. He was very well connected into the production community in Chicago and I was not. So I arranged with Steve to be the producer and I said to him, "I need a co-writer."

There was a theater company in Chicago called The Organic Theater Company. The Organic was a really wild bunch of characters who had quite a bit of success in Chicago and were a really interesting theater company. One of the company members was Richard Fire, another was Tom Towles, who would play Otis. Other members of the company were Dennis Franz, Dennis Farina and Joe Mantegna. They had worked with David Mamet, they had produced Sexual Perversity in Chicago.

They did a play called Warp that was kind of an outer space fantasy and Steve Jones had done a bunch of video projection for them and knew the group. Steve recommended Richard Fire. Richard and I met and talked about the project and I hired Richard.

What was your working process with Richard?

I would go every day to Richard's apartment and we would sit and he would type. We would knock ideas back and forth and then when we came to what we thought was something worthwhile, he would type it out.

What's so interesting about the script is that -- if you take out the violence -- it's a very traditional, well-structured story. We meet Henry, he meets his friend's sister and a romance starts and then there's a fight and then he and the sister leave together. It's almost like a classic 1950's Paddy Chayefsky television play.

I brought the exploitation elements to it and Richard brought traditional dramatic skills to it. We made a very good team, because had it been left to me it probably would have been tilted more toward pure exploitation. Whereas Richard humanized it. Paddy Chayefsky is a good example. On the DVD, Richard talks about the Aristotelian unity of time, place and action from classic dramatic writing. I think his presence certainly elevated the script.

Did you set out to make such a controversial movie?

I intended to make something very shocking. I remember, in my youth, pictures that sort of crossed the line. Back in those days there would be these incredibly lurid radio advertisements that if you listened to rock music on the radio a lot -- like most kids in my generation did -- they had these incredibly lurid campaigns for pictures like Last House on the Left and Night of the Living Dead and Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Those pictures were sort of watersheds, alongside pictures like The Wild Bunch. The Wild Bunch was incredibly shocking; up until then in a Western, if somebody got shot they fell down. There was no squib work, there was no spouting blood.

So our thought was, "Okay, we've got $100,000 and a chance to do a film and it's going to have to be a horror film, so let's make a horror film that is going to horrify." Richard Fire and I set ourselves a goal, and it was if we're charged with making a horror film, then a) Let's redefine the genre, and b) Let’s totally horrify the audience.

Like many things, the words "horror film" are like "liberal and conservative." The original meanings of the words have gotten lost. One would think that conservatives would be interested in conserving the environment, because the word comes from conservation. When you think of "horror film" now, it's a set of conventions and we meant to defy those conventions. The genre often includes monsters, creatures from outer space, ghosts, the supernatural or something beyond reality. But we didn't have a budget for any of that, so we set ourselves the goal of, "How can we most completely horrify an audience without using the traditional conventions?"

Was there any downside to ignoring the traditional conventions of the genre?

Well, when we did the home invasion scene, it was a pretty creepy feeling after finishing that scene. A lot of the stuff -- fake blood and all that stuff -- there's a certain fun factor to doing it on the set. It's kind of silly, it's fake blood and rubber heads and all that kind of thing. But when we did that scene of the slaughter of the family it left a really strange atmosphere in the room. We did two takes. It was pretty horrific stuff and we didn't know how an audience was going to react to this.

Was the use of videotape in the home invasion scene an aesthetic choice or an economic choice?

Absolutely an aesthetic choice. The video image had an immediacy that the film image did not have, so when we had them tape that home invasion we very specifically chose to use video because it does have that immediacy and that reality. It lacks that distancing and softening that film gives. Also, having grown up watching the Vietnam war on television, even though those were 16mm film cameras, there was a quality to that hand-held footage that made it more real and more shocking.

Also I had read the book Red Dragon. In Henry Lee Lucas' case, they did not photograph or videotape their crimes. But in Red Dragon, Francis Dolarhyde worked in a film processing facility and he would go out and kill these people, photograph them, then come back and process the film. That book was a couple years old and by that time you could buy a decent home video camera, you didn't need to go through a lab.

The use and intensity of violence, from the static images that open the movie to the crimes we ultimately see Henry and Otis commit, seems very planned and measured. Was that the case?

With violence and action, you have to keep topping yourself. If you go backwards, the audience is going to be disengaged. So the violence was doled out and increased as the story went along.

How did you come up with the idea of opening the film on a series of tableaux of Henry’s recent crimes?

Richard and I were sitting in his apartment and we had various materials -- this was before the Internet -- and we were quite limited as to what we could come up with compared to today. But we did have that 20/20 documentary and it did have images. One of the famous images was of a young woman who was allegedly murdered by Henry. She was a Jane Doe who was never identified. She was left in a culvert somewhere and she was nude but for a pair of orange socks. And she was always referred to as Orange Socks because there was no other way to identify her.

We were thinking, "What's our opening?" And we happened to be watching the 20/20 show and there was that photograph of Orange Socks, and Richard just went, "That's our opening."

That was indeed our opening, although we didn't have orange socks, we used pink socks. Once we established that, we decided to do a series of them.

The audience can only take so much. You'll notice that one of the bloodless ways we had them kill people was to snap their necks, which is how he kills the woman and the young boy in the home invasion. There's no overt gore.

We were borrowing from the exploitation genre but to me the movie is a character study about people who did extremely horrific things. And there's the horror. Again, not from monsters from outer space.

In the case of stabbing Otis, he's such a heinous character that he deserves it. When we stabbed him in the eye with that rat-tail comb, you can't believe how much laughter there was on the set with that silly looking head and the blood. It was kind of fun.

Each individual can create in their imagination something more horrific than the graphic expression you may be able to come up with, especially on that kind of budget. A great way to put across scenes of great mayhem is to lead the audience up, step by step, so they can see what's about to happen. It's very clear that somebody's about to get killed. If you lead the audience, shot by shot and step by step up to the deed and make it very clear what's about to happen and then give them a couple frames and then cut away to some other thing, but continue it with the graphic sound, I think it can be much more horrific. Each individual will be left to complete the horror in their own mind, from their own library of personal horror.

Again I have to credit Richard Fire for insisting that we make a serious drama rather than just a piece of pure exploitation.

The visuals are very clever, like the use of the guitar case to signal that Henry has killed the hitchhiker. Or Otis' sister's suitcase, which is used for comic effect when we first see it and then has a far grimmer use at the end of the film.

We had a fair amount of time to work on that script, which you don't often get. In Hollywood they say, "Okay, the money's here, you've got this actor, let's go!" I just shot a segment for Masters of Horrorand normally they give you a seven-day prep, but since one of my days was Canadian Thanksgiving, I got a six-day prep. It's hard to iron out the details in that amount of time.

Once you lay out your story and your script, then you start to see these connections that can be made to really strengthen that through-line, so everything connects in some way or another. If you have time, you can work on those details. If you don't, you just shoot the script and hope for the best.

Did you write with any specific actors in mind?

No. We had the Chicago theater community to draw from, which is pretty rich. A lot of young actors come to Chicago to learn their chops because there's a lot of Equity theater where you can actually make a living working in theater. Unlike Los Angeles, where most of it is non-Equity so you don't really get paid.

Chicago's a cheaper place to live, so a young actor can make their way with perhaps a bartending job or waitress job, and when they're working in theater they actually make enough money to pay their rent in the Bohemian neighborhoods of Chicago.

What was the refinement process on the script before you shot it?

The refinement process was mostly with the actors. There weren't that many people in my circle who had wide knowledge of production. Most of the experience in actual film production in Chicago was in commercials. Occasionally a movie came to town, but that was not the bread and butter of Chicago, it was commercial production. At the time Chicago was the number two market, after New York, for commercial production.

Our actors came out of theater, so the script refinement was done with the actors in rehearsal. Tom Towles came from the Organic Theater, where Richard Fire was a member and they'd known each other forever. And Tracy Arnold also came from the Organic, although Tracy was more of a new arrival, she had only been with the company for a year or two. Michael Rooker was just a lucky find.

How did you use the rehearsal process?

I've worked this way almost ever since, when I'm fortunate enough to get rehearsals. If I can get two weeks or at least ten days with them, I'll work with the actors myself for the first half of the rehearsal period. And then once we get the shape of the thing I've almost always brought the writer in, because the actors will want to make changes, like, "My character wouldn't use this word," "My character wouldn't say it this way," "I can't get my mouth around this phrase, it doesn't feel right to me."

Once the actors take on those characters, they know them in deeper way often than the creators do. But if you just open the door and say, "Sure, go ahead, change it," you're going to have a disaster on your hands because then everything will start to change. But if you bring the writer in and if the actor tells the writer the line they'd like to change and their reasoning, then if you allow the writer to tailor the line, you still have the writer's voice but you also have the actor's notes. I think when you work that way you get roles that are like custom-tailored clothing. They're tailored to the particular actor and their personality and their needs and their interpretation.

On the first day of rehearsal, Richard told the actors, "Okay, I want you to go home and write a character bio, all the backstory, all the family history." Since Tracy and Tom were both part of the Organic Theater this was common to them, but to Michael it was sort of an affront. So Michael actually went home and, truth be told, while he was sitting on the toilet he dictated his backstory into a little portable tape recorder.

They each came back to rehearsals with these backstories and a certain amount of that information then got worked into the script for each character. It was a lesson to me that I carry because it was invaluable.

How have you used this technique since then?

Well, when you're working with Bob DeNiro, Bill Murray and Uma Thurman you don't necessarily send them home to write character bios. But you work with them in readings and discussions for four or five days. Then once you've really gotten the shape and everybody's in the same movie, then you bring the writer in and you use the writer to explain to them why things are the way they are. If they want dialogue changes, then you let the writer do it for them so that a voice is maintained rather than just throwing the doors open and letting everybody re-write your dialogue. You'll regret it if you do that.

Did you make any choices in the writing that you knew would save you money in shooting?

Well, a major one was setting it in Chicago. So far as anyone really knew, Henry Lee Lucas had never been near the city of Chicago. But there was no way we were going to go out on the road with a crew and house them and feed them.

What's the best advice you've ever received about screenwriting?

Probably, strangely enough, it was in Syd Fields' book. I had read other books on screenwriting and filmmaking that tended to take a more academic, ivory tower appraoch to the artistic principles involved. Syd Fields' book was just the nuts and bolts.

"Know your ending" was one thing I got out of that book. I live back and forth between Chicago and Los Angeles and I love road trips. When I come out to do a project I'll drive out and when the project is over I've drive home. It's a three-day drive and I think a lot and clear my head. It's like a chapter in my life is beginning and a chapter is ending. But I always know my destination. I know where I'm going, so I can plan my route. It's the same thing with a script. You need to know where the story's going.

One of the principles that he laid out in his second book was the midpoint. The dramatic arc goes up and it comes down. It starts at the beginning, goes up to a peak, comes down to the ending. And the midpoint is the peak.

But most movies get in trouble in the middle. Establishing a midpoint for me was like knowing that I was going to drive from Los Angeles to Chicago, but I'm going to stop in Omaha. That was really an incredibly helpful idea, because after you leave the first act you're driving to the midpoint. You're going up. Now when I'm working on a script, once I've read it, I'll go to the last page and take the page number – let's say it's 120 pages – and I'll go look at what happened on page 60. I want to see if there's a key event that sort of divides the story in half.

In good screenplays, it may not be exactly on page 60. It may be between 58 and 63. But almost always in a good story you'll go back and find a key event that takes place that divides the story in half.

Dying to make a feature? Learn from the pros!

"We never put out an actual textbook for the Corman School of Filmmaking, but if we did, it would be Fast, Cheap and Under Control."

Roger Corman, Producer

★★★★★

It’s like taking a Master Class in moviemaking…all in one book!

Jonathan Demme: The value of cameos

John Sayles: Writing to your resources

Peter Bogdanovich: Long, continuous takes

John Cassavetes: Re-Shoots

Steven Soderbergh: Rehearsals

George Romero: Casting

Kevin Smith: Skipping film school

Jon Favreau: Creating an emotional connection

Richard Linklater: Poverty breeds creativity

David Lynch: Kill your darlings

Ron Howard: Pre-production planning

John Carpenter: Going low-tech

Robert Rodriguez: Sound thinking

And more!

Write Your Screenplay with the Help of Top Screenwriters!

It’s like taking a Master Class in screenwriting … all in one book!

Discover the pitfalls of writing to fit a budget from screenwriters who have successfully navigated these waters already. Learn from their mistakes and improve your script with their expert advice.

"I wish I'd read this book before I made Re-Animator."

Stuart Gordon, Director, Re-Animator, Castle Freak, From Beyond

John Gaspard has directed half a dozen low-budget features, as well as written for TV, movies, novels and the stage.

The book covers (among other topics):

Academy-Award Winner Dan Futterman (“Capote”) on writing real stories

Tom DiCillio (“Living In Oblivion”) on turning a short into a feature

Kasi Lemmons (“Eve’s Bayou”) on writing for a different time period

George Romero (“Martin”) on writing horror on a budget

Rebecca Miller (“Personal Velocity”) on adapting short stories

Stuart Gordon (“Re-Animator”) on adaptations

Academy-Award Nominee Whit Stillman (“Metropolitan”) on cheap ways to make it look expensive

Miranda July (“Me and You and Everyone We Know”) on making your writing spontaneous

Alex Cox (“Repo Man”) on scaling the script to meet a budget

Joan Micklin Silver (“Hester Street”) on writing history on a budget

Bob Clark (“Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things”) on mixing humor and horror

Amy Holden Jones (“Love Letters”) on writing romance on a budget

Henry Jaglom (“Venice/Venice”) on mixing improvisation with scripting

L.M. Kit Carson (“Paris, Texas”) on re-writing while shooting

Academy-Award Winner Kenneth Lonergan (“You Can Count on Me”) on script editing

Roger Nygard (“Suckers”) on mixing genres

This is the book for anyone who’s serious about writing a screenplay that can get produced!

Henry Jaglom on “Someone To Love"

What was the inspiration for “Someone To Love”?

HENRY: I was alone, and I didn't understand why I was alone. And I looked around at my friends and I realized that I was part of a whole generation of people that were alone and that it wasn't just a generation but that it was a function of something that was happening at that period in the 80s and the 90s. People who always assumed that they would be married and have families found themselves somehow in the middle of their lives on their own.

So, I thought I would try to make a movie about it, but what I would do is go through my phone book and actually pick out people I knew who were alone and put them together in some central location.

And then I was talking to Orson about it at lunch one day. He and I had lunch once or twice a week for the last eight or nine years of his life. He was very interested in it.

And during that time, I was editing my film Always, about the end of my first marriage (which was the reason I was alone at the time of Someone to Love). Orson came one day and sat behind me in my editing room and watched the entire film of Always and smoked his big, Monte Cristo cigar.

At the end of it he did an extraordinary thing. He was silent for a while, and I thought, 'Oh, Christ, he hates my movie.' And then he said something very quietly, so I couldn't hear him, which was not like him. So I said 'What? What?' And he said, 'I'm jealous.'

For a crazy moment I thought he meant he was jealous because the film was so wonderful; he didn't mean that at all.

But I tried to reassure him, I said, 'My God, you're Orson Welles, you've made a dozen of the greatest films of all time.' He said, 'No, no, Henry, I'm not jealous about that. It's a very good film, I like the film very much. I actually love the film. But I'm not jealous because of the film. I'm jealous because you, as a filmmaker, in Always reveal yourself completely, nakedly, without any masks on. You don't make yourself attractive, you show yourself warts and all. As a matter of fact, you're going to get criticized for some of the whining and the baby talk and all of that. You really allow us to see you without a mask on.'

And Orson said, 'All my life I've hidden behind a mask. I've never been on screen without a mask. I'd like just once before I die to do that.'

So I said, 'Well, Orson, you just heard about my film Someone to Love. I think we've got a solution here.' He said, 'What do you mean?' I said, 'It's all about my generation of people and all of us trying to figure out why we're alone in life. If I had somebody from your generation -- you -- sitting in the back of the theater as a sort of Greek chorus and telling us just as you have at lunch over these years, talking to me about life and death and love and loss and men and women and movies and theater. If you'll do that, we'll do it without masks. You'll get to appear without a mask.'

And Orson said, 'Great.'

Then he showed up three months later, when we started shooting, with a big make-up box in his lap and was made-up like a Greek. He had a funny, weird accent and he had a big nose on. I said, 'What are you doing? Remember, the whole point of this was no masks.' He said, 'Oh, you don't like the Greek? Come back in a half hour.'

I came back and he'd put on some Arabic make-up and had an Arab accent. I said, 'Orson, you're missing the whole point. The whole point was, no masks, remember like in Always, we want to see you.' He said, 'Oh, nobody wants to see me just with this little nose.'

I don't know how to explain it. He was goading me into tricking him (though of course you couldn't trick Orson, so it was his manipulation) into tricking him into doing the film the way he really wanted to but couldn't admit it finally. He allowed me to say, 'No Orson, no make-up, no accents, I don't want you to memorize speeches, I want you to really be you and just help me solve my dilemma but also help me solve the movie, because I don't know how to end this movie, there's no way to end it.'

So he said, 'Oh, I'll give you an ending!'

I had a plan, a super structure, but I left it up to the individuals as to what they would say, and I certainly left it up to Orson as to what he would say and depending on that was what I would say.

I knew what I wanted to talk about in terms of loneliness and relationships, but I was actually seeking the movie as I was in the movie. I decided I would just do it that way and then when I got back to my editing room, I would look at what I got and what everybody gave me and find a way to put it together into a narrative.

How much of your plan did you reveal to your cast?

HENRY: No one knew anything. I just told them I wanted them to be in a movie, and I wanted to be able to deal freely with the facts about their own single situation in their romantic life at this moment. I confirmed with some of them that they were in fact still single, that they weren't involved, that I didn't miss anything, and that's all I asked them to do.

And only one person ended up leaving. Kathryn Harrod left, she didn't realize it would be that personal. The truth was, she was uncomfortable, and I thought more people would be uncomfortable, but actually everybody likes to talk about themselves.

How much did you find that movie in the editing?

HENRY: One hundred percent. Actually, fifty percent in the shooting and fifty percent in the editing. But nothing in preparation. It's the kind of movie where you absolutely cannot prepare, because you don't know what people are going to say.

Several of my movies have a mixture of a storyline -- which is a narrative, which is created by me -- and an interview structure, which is spontaneous and real and comes from the people. So, I can prepare one half of that, but I can't possibly prepare the interviews without interfering with the reality of it.

Like in Eating or in my movie coming up next, Going Shopping, or Venice/Venice, anyone one of those movies which have an interview threaded throughout.

But in the case of Someone to Love, because the entire thing was about somebody making a film, there could be no preparation. It would be absolutely wrong for me, from my point of view, to have anybody know anything in advance of what anybody was going to say, including Orson. All I told Orson was to go over in his mind all the things he'd talked to me about over the last couple of years when we'd talked about relationships and men and women. And then he just came up with all this stuff.

It really captures Orson the way if you had had lunch with him. Everybody had this image of him as this intimidating ogre. If he had a chance to, he might put on a little bit of scary persona, but in fact he was a sweet, sweet man, and I think that's what shows in the film.

The narrative is created in the editing rather than written beforehand, and that's true of many of my movies. Orson said to me once, 'Everybody else makes movies, but first they decide what the narrative is, and out of the narrative they try to find their theme. The difference with you, Henry, is that you choose your theme first, and then you try to discover, out of your theme, the narrative.' And that's very true of my process.

I didn't set out to work this way. It's the way I like finding stories.

During the making of Someone to Love, Orson looked at me suddenly and said, 'I know what's going on. You remind me of this old Eskimo I say in a documentary about Eskimos. There was this old Eskimo, who was sitting and carving this gigantic walrus tusk. And the filmmaker goes up to the Eskimo and says, "What are you making?" And the Eskimo looks at the filmmaker, totally bewildered, and says, "I don't know; I'm just carving and trying to find out what's inside."'

And Orson said, 'That's the way you make movies, Henry, you carve away at yourself, at me, at your friends, at the whole culture, trying to find out what's inside of all of us.' And that was as good a description of my process as I've ever heard.

I understand that you don’t like rehearsals.

HENRY: I hate rehearsal.

What’s the benefit of not rehearsing before you shoot?

HENRY: The magic of reality. The honest surprise of what happens the first time when somebody thinks of something or you see them thinking and discovering it and saying it. And then they have to re-create it and try to pretend to be thinking and discovering it.

You can't do this on stage, where you have to repeat everything at 7:45 at night the exact same way, but on film you just have to get it once.

And the most truthful moments, it seems to me, are the moments that just happen and even surprise the person themselves as they're saying something, because they don't know they're going to be saying it. If you rehearse, no matter how good you are, you know you're going to be saying it. And unless you've got a Brando or a Meryl Streep or the handful of actors who are better each time, you've got human behavior which is better and truest the first time.

God, I would die if I rehearsed and someone in rehearsal gave me a great moment, because a great moment is what you look for in film. It's all about the moment.

I was complaining about not having more time, not having more money to do something I wanted to do, and Orson said this line that I now have over my editing machine. He said, 'The enemy of art is the absence of limitations.'

That was just about the most important thing that has ever been said to me, because if you don't have limitations you start throwing technology or money at a problem. But if you have a limitation, you have to find a creative solution, and therefore you create art.

For me the most valuable lesson from Orson, and it happened during that movie, was make whatever happens work. It's good to have limitations, because you have to find an artistic or creative way to surmount them. And it's more fun.

Did I tell you why I started improvising in movies?

To make my first movie, A Safe Place, I had to write a script to get the money from Columbia Pictures. I had written a play called A Safe Place, so I adapted it into a very funny screenplay. It was a more hip version of a Neil Simon thing. The studio loved it, everybody loved it.

My two friends, Jack Nicolson and Tuesday Weld, two of my very closest friends, I knew them extremely well and I'd written this wonderful scene and it was really good and I'd done it on the stage and it worked beautifully.

So I had them do the scene, and they're tremendous actors, but there was something missing and I didn't know what. So I said, 'Okay, let's do it again.' And I did about five takes, and I said, 'This is really strange. This isn't as interesting to me as Tuesday actually is or as Jack actually is in life.'

So I said to them, 'Look, just forget what I wrote. You know what has to be accomplished in this scene. Just get through that, but don't worry about my words.' And it was magical. And I didn’t look at the script for the entire rest of that movie, to the horror of Columbia pictures, because I can't it into a poetic and abstract film from what was a very simple narrative.

The bigger lesson that I got was that actors are to be encouraged to delve into their own lives and into their own expression and their own language and their own memory, because they will come up with fresh and extraordinary things that you could never in a million years create.

And all you have to do is get that to happen once on film and have that moment and then figure out how to put it together with the next moment. For me, that was it. I never looked at my script again. I drove the crew crazy, but I made the movie I wanted to make.

How do you edit?

HENRY: I edit on film, on a KEM, on a flatbed.

You’re a good candidate for non-linear editing.

HENRY: Everybody tells me that. But what I like to do is splice myself, go back and forth over a piece of film, find things, find things that I otherwise would have missed. I don't know, maybe I've become a reactionary in this area; it seems hard to believe.

I was the first person to have a KEM. It was because of Orson, once again, telling me on A Safe Place, after I shot the movie. Everybody was still cutting on movieolas. And he said ' There's this great thing, a flatbed KEM,' and all the editors didn't want to get it because they realized that they could be dispensable then, because you could learn how to do it yourself.

Which is in fact what happened, and halfway through A Safe Place I let the editor go and I ended up editing it myself. And I've edited all my movies since. So maybe it's just the familiarity of that to me, and if I had the other I would need a technician, that I don't want to work with.

I guess, it's old dogs and new tricks.

You have very strong critics. Some people just seem to hate your movies.

HENRY: My movies violate a lot of the conventional rules of filmmaking, which people really resent. They really resent that, I don't know why, I didn't expect that, but I found that out starting with my first films. They see film as a narrative medium, and they don't see it as an art. They're willing to accept in music or in painting, even to some extent in theater--a sort of surrealist thing, where lights are used and sets are used, but they're not naturalistic.

But on film, they want to know where they are. It's become such an entertainment rather than art medium, that when you defy that and make people explore certain things emotionally or violate some of the rules.

I found, on A Safe Place, because I violated all of those rules on my first movie, because I didn't know people were going to resist it, the anger started right there.

I remember Time magazine saying 'this movie looks like he threw the pieces of the film up in the air and it landed totally at random in a mix master.'

But I think that those people who don't like that really hate it. They feel violated. Then they translate that as I am either amateurish or self-indulgent or all those kind of words, because I don't think they like to be taken out of their narrative convenience, out of the safety of the narrative.

We deal so much with people revealing themselves, people really expose themselves in my movies, these wonderful, brave actors. I had about 53 of them in Going Shopping, I had 38 of them in Eating. These aren’t just actors who are good actors; they're revealing and opening up very personal and frequently painful parts of themselves and exposing it.

And a lot of people don't want to see that. It's understandable. I'm always surprised by how many do (want to see it). I'm never surprised by the negative reactions; I'm always surprised and delighted by the degree of openness with which so many people are willing to receive and accept the films.

And those people who do like them, they really do become a part of their lives. I get these incredible letters, thousands of letters from all over the place, with very touching things about terribly sad and painful moments in these people's lives when the films were really helpful. They feel less alone, they feel less isolated, which is really the goal for me of making films like this.

Dying to make a feature? Learn from the pros!

"We never put out an actual textbook for the Corman School of Filmmaking, but if we did, it would be Fast, Cheap and Under Control."

Roger Corman, Producer

★★★★★

It’s like taking a Master Class in moviemaking…all in one book!

Jonathan Demme: The value of cameos

John Sayles: Writing to your resources

Peter Bogdanovich: Long, continuous takes

John Cassavetes: Re-Shoots

Steven Soderbergh: Rehearsals

George Romero: Casting

Kevin Smith: Skipping film school

Jon Favreau: Creating an emotional connection

Richard Linklater: Poverty breeds creativity

David Lynch: Kill your darlings

Ron Howard: Pre-production planning

John Carpenter: Going low-tech

Robert Rodriguez: Sound thinking

And more!

Write Your Screenplay with the Help of Top Screenwriters!

It’s like taking a Master Class in screenwriting … all in one book!

Discover the pitfalls of writing to fit a budget from screenwriters who have successfully navigated these waters already. Learn from their mistakes and improve your script with their expert advice.

"I wish I'd read this book before I made Re-Animator."

Stuart Gordon, Director, Re-Animator, Castle Freak, From Beyond

John Gaspard has directed half a dozen low-budget features, as well as written for TV, movies, novels and the stage.

The book covers (among other topics):

Academy-Award Winner Dan Futterman (“Capote”) on writing real stories

Tom DiCillio (“Living In Oblivion”) on turning a short into a feature

Kasi Lemmons (“Eve’s Bayou”) on writing for a different time period

George Romero (“Martin”) on writing horror on a budget

Rebecca Miller (“Personal Velocity”) on adapting short stories

Stuart Gordon (“Re-Animator”) on adaptations

Academy-Award Nominee Whit Stillman (“Metropolitan”) on cheap ways to make it look expensive

Miranda July (“Me and You and Everyone We Know”) on making your writing spontaneous

Alex Cox (“Repo Man”) on scaling the script to meet a budget

Joan Micklin Silver (“Hester Street”) on writing history on a budget

Bob Clark (“Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things”) on mixing humor and horror

Amy Holden Jones (“Love Letters”) on writing romance on a budget

Henry Jaglom (“Venice/Venice”) on mixing improvisation with scripting

L.M. Kit Carson (“Paris, Texas”) on re-writing while shooting

Academy-Award Winner Kenneth Lonergan (“You Can Count on Me”) on script editing

Roger Nygard (“Suckers”) on mixing genres

This is the book for anyone who’s serious about writing a screenplay that can get produced!

Stephen Belber on writing "Tape"

Three people in one room.