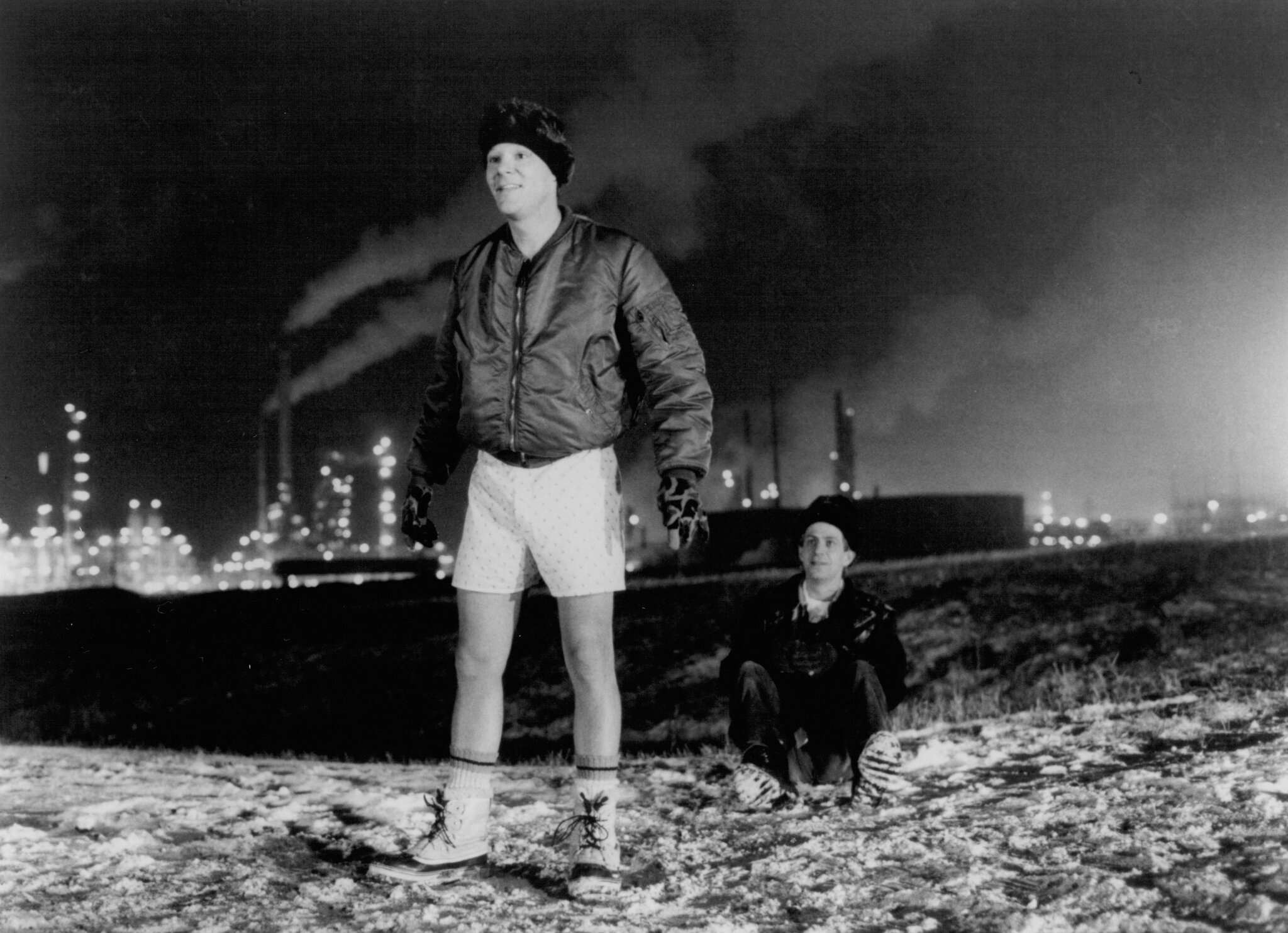

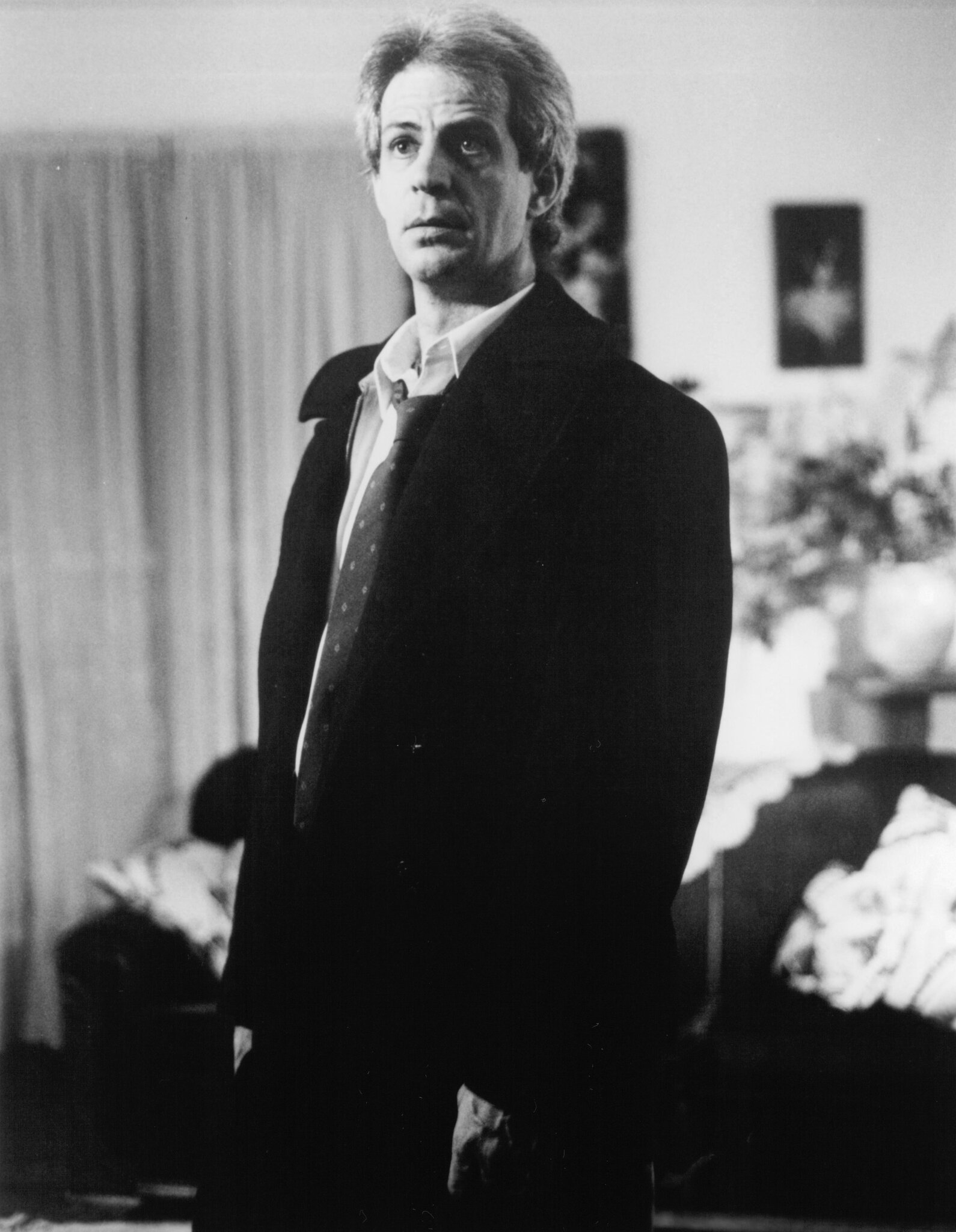

Whit Stillman's Metropolitan exists in a timeless New York past brimming with debutant balls and ultra-classy cocktail parties. His clever examination of this universe is set primarily at after-parties, allowing him to comment on the upper class without going to the expense of recreating their soirées.

This true comedy of manners, based on Stillman's own experience of skirting the upper crust, put him on the map as a filmmaker to watch and resulted in a well-deserved Academy Award nomination for his literate and witty screenplay.

What was going on in your life and your career before Metropolitan?

WHIT: I was in transition. I had a journalism job; it was for a publication where they overpaid us a bit and they went out of business. So I was left in 1980 with some savings and I wanted to get into the film business.

On a trip to Spain, I read a Variety special issue on the Spanish film industry, which showed that there were opportunities to sell Spanish films in the United States. I met a few Spanish filmmakers on my trip, talked to them about the opportunities to sell their films in the United States, and I ended up within a year being a sales agent for a lot of really good Spanish films.

So I did that from 1980 until 1983 and that was when it really starting paying off, in the sense that one of the filmmakers, Fernando Colomo, came to New York to make his own film, Skyline, and I helped him on it. It was made for nothing, with a four-person crew and one comic actor brought over from Spain.

We re-enacted Fernando Colomo's real experiences in New York, so I was in the film in an analogous role to my real role with Fernando. The film turned out really well, it was in the New Directors series at the Museum of Modern Art and got a release and good reviews and did really well in Spain.

That same summer, another filmmaker I was representing, Fernando Trueba, who did the film Belle Epoque that later won the Oscar, made his second film, and I was hired to play the Stupid American, an annoying character. I was in Madrid quite a bit that summer -- since I was an unimportant guy they could schedule around me -- so I had long weeks of waiting. With the per diems, I made more money than I think I ever did as a foreign sales agent for Spanish films. It was right before that shoot that I started to write the script for Barcelona. And I realized, as time went on, it was too big and ambitious a project to do first.

In the summer of 1984 I had an idea of a film I could do cheaply, which was Metropolitan. So I put aside the work I'd done on Barcelona and started working on that. Also, I had to take over a family business -- an uncle's illustration agency, representing artists and illustrators in New York -- and that became my day job. That anchored me to Manhattan and I started thinking of this Manhattan idea for a cheap film that would look good.

From childhood I remembered a production of Shaw's Don Juan in Hell, which all took place in one room and I thought that this was, theoretically, a film that could be shot in a room. You'd just have people all dressed up in some fancy room and there it is.

Of course, in writing the script it went different places, but that was the premise.

Were you drawing on your own experience to create those characters and those situations?

WHIT: I was, but it was long enough ago that it was shrouded in the mists of time. But the idea of the group was sort of based on a group, the rat pack was based on the rat pack, there was a funny, snobbish character who was like the Chris Eigeman character, Nick Smith. But really it was fictional, it was all made up. There were some people who were sort of like someone or other, but it had to be created anew and that's what always takes me a long time.

You've coined the phrase "social pornography" to describe the movie. Can you define what you mean by that?

WHIT: What I mean by that is that it's a taboo to talk about this kind of society in the United States; it's not supposed to exist. And there's a feeling of disgust and excitement in talking about the idea of Americans who camouflage themselves as upper middle class but really think of themselves as upper class.

On the surface, the idea doesn’t really lend itself to a low-budget treatment: a lot of characters, a lot of short scenes, a lot of locations -- some of them high-end -- and plus it's a quasi-period piece. Did you consider any of those issues while you were writing?

WHIT: Well, I remembered how cheap it was for me to go to those parties. It didn't cost me a dime, it was the least expensive part of my life. And so I thought, in a way, the film could be done the same way. If people donated tuxedos and a location, it would look rich but it's not.

I knew that for a very minimal amount of money you could get permits to shoot on the streets of New York, so you had a beautiful set for free. And moving around doesn't really cost that much. In a way, it's more expensive to stay in one place, because you really need to lock down the location and not have a chance of losing it.

One of our rules was that we wouldn't shoot in any apartment where we couldn't finish the scene in that day, because we assumed we'd be kicked out of the place. The lengthier apartment sequences were actually done in townhouses faked to look like apartment buildings.

One of the eureka moments for deciding to do the project, if I can use that term, was the director of one of the Spanish films I sold was talking about the actual cash budget for the film he had done was $50,000. And at that time I knew that -- if we bought our rental apartment at an insider price, held it for a year and later resold it -- theoretically we could make $50,000 on our apartment. That number encouraged me, because I knew I could write a script for that money. To finish it, I'd need other people's money, but I could start it with my own.

What was your writing process like on Metropolitan?

WHIT: I actually dreaded the thought of writing alone. I had written short stories and gotten some good reaction; I'd been commissioned by Harpers to write a story and people like them. Tom Wolfe was quoted as liking one of the stories. But I hated the solitary writing process.

So I actually started writing Metropolitan with a college friend -- not exactly a college friend, a fellow who hung around college without actually going there. We sat around, talking about ideas, for about three hours and I realized that wasn't going to work. And so I went and wrote the script.

It was good because I had this interesting job that was sort of challenging, representing artists, and I liked the vicarious work of being an agent for people whose work I liked. It was a social job, where you had lunch with people and saw a lot of people and it was a good day job while I was writing the script. It meant that I could take two weeks without writing anything and then I'd get in an intense mode, then I'd have vacation where I'd expect to write all the time but instead I'd get excited about another topic and write a stupid article for a newspaper. It allowed time to pass and let me reconsider what I was doing.

At a certain point I decided that the Tom Townsend character really wasn't sympathetic, because he was in love with the girl he shouldn't have been in love with and he ignored the girl he should have liked, and that really the sympathetic character was the Audrey Rouget character and the film should be about her. I tried to make the film about her, but I realized that too much is involved in the Tom Townsend character, I'd done too much of that and was too attached to it. So I gave up making it explicitly Audrey's film, but a lot of what remains having tried to make it Audrey's film is still in the movie.

And then I thought the important thing in film is how you end it. So the challenging thing was where was all of this going to go? And so I started writing the end of the movie. I had a process where I had the first three-fifths of the movie and the last fifth of the movie and I had to attach them at some point. For me, it was like the transcontinental railway and finding where would the golden spike be to attach these two ends of the narrative.

How did you do that?

WHIT: I can't remember exactly, but there was a year where the tracks would never quite sync up. It ended up working.

How was that process different from how you work now on studio projects?

WHIT: I think it was good writing a film that wasn't in the development process, because I'm not sure it's very helpful having a lot of voices in on the creation of a script. I think they try to smooth things and homogenize things and explain things. It's better making it a kind of goofy voyage and ride, when you have to just be honest with yourself about what you're doing and where your mistakes are and what isn't working.

On Metropolitan, I found the least helpful comments were from people who thought they were in the film business. Unsuccessful screenwriter friends, who were very, very critical of certain things, while my sociology professor/godfather was very, very supportive and loved the things that the screenwriter friends said were breaking the rules.

Do you remember what their criticisms were?

WHIT: I remember I had this long monologue that the Chris Eigeman character recites about this girl, Polly Perkins. It went on for pages and pages. My screenwriter friend was indignant about how terrible that was and my sociology professor/godfather thought it was a wonderful story.

What I found when we shot the film was that there were long speeches that didn't work, but they were the sociological speeches by the Charlie character, played by Taylor Nichols. If it was a very long sociological speech, we really had to fight hard to whittle those down and make them pertinent, while the long narrative about Polly Perkins, although it's just one guy talking, actually works perfectly fine. It's a story. People are interested in hearing a story. And film is so wonderful in the sense that you can have people's reaction.

How long was the whole writing process and how long were the gaps where you just let it gestate?

WHIT: I would say the gaps would be a month or two. It was slightly more than a four-year process. I started in the middle of the summer of 1984. I finished four years later in August of 1988 and went out to try to find people to produce or invest in the film. I think I did another draft where I cut things, to try to make it more production friendly. But the actors had already seen the older script, so often we'd restore stuff.

How long was the script?

WHIT: It was very, very long.

Also, I didn’t really get into film formatting too much; I didn't really see the point of centering the dialogue, because my computer skills in those days weren't so good as to have to re-tab all that. I remember a woman at the Tisch School refusing to help us with casting because it wasn't in proper screenplay format, therefore we weren't serious.

That's why I don't take people very seriously when they criticize a script for being too long. I don't think we cut any scenes but one -- it's a very brief phone conversation between Tom Townsend and his father, and it came off as mawkish. The line producer, Brian Breenbaum, made a very funny, cutting remark about it: He said, "Put it in an envelope and mail it to your father."

The other cutting we did was cutting within scenes, to try to whittle things down and pick up the pace. And of course we cut out all the improv stuff. We came up with some jokes that we thought were funny on set and we ended up cutting them out.

Did the actors have any problems with the long speeches and the heightened language?

WHIT: Nope. It's good for them, I think. I think it's good for actors to have a lot of words to say, they seem to like it.

Did you do any readings of the script before you finished it?

WHIT: There was a casting reading of it -- after we had done most of the casting we had a read-through.

It was odd, because I had had the Charlie character have something of a stutter in the script. And then I thought, "This is too hard. We've got so many hard things to do, let's not have another hard thing with a guy stuttering through all this dialogue." And I thought it might sound fake, someone acting a stutter.

And then, in the read through, Taylor stuttered a couple of times, and there was one moment when it was a little bit too much. And I stopped the reading and said, "Actually, the idea of this character is he should stutter, so if you can do that, it's great." Taylor completely dominates his stammer, he can do a flawless performance. But he did have a stammer in childhood, and he brought it out for that part. I found it fantastic; somehow a stammer is like when an actor eats. Eating and food and business of that kind in a film is usually wonderful, people are relaxed. And the stammer was kind of the same, it made things really real and unrehearsed.

One of the great things about the script was that these characters are very likeable, even at those times when they may not be behaving in a likeable manner. Was that planned?

WHIT: That was the intention. I think we give them their problems. They do have that reality in their sad sack qualities and a lot of it is the success of the performance by the actor. It's a thing I've noticed: Some actors can do a technically perfect performance of scripted lines, but there can be a warmth that's lacking, a human quality, that takes away from what's intended. In this case, our cast delivered the warmth.

Did you write with any actors in mind?

WHIT: Yeah. I wrote with Audrey Hepburn in mind. The Audrey character is Audrey Hepburn. I did not write with known actors in mind. I knew that known actors wouldn't do it. It didn't occur to me which known actors would do it; only actors from the past -- like Audrey Hepburn -- who is the aunt of the actual Sally Fowler.

Although it's a talky film, you also made good use of just showing us things, without commenting on them. For example, when Tom Townsend finds his childhood toys have been thrown out by his father. We never see him come back for the toys, but they simply show up in his room in later scenes. Those scenes could have been painful to watch …

WHIT: It was painful to watch; we actually cut some stuff out there. We had a mawkish scene, going back to the box. We shot it and cut it out.

Why did you choose to set the movie in a sort of timeless past?

Well, in my head it was in the past and I couldn't afford to set it in a specific past. So I had to just try to do the best we could for a past identity to the film by trying to exclude what we could exclude and include what we could include, without stating anything too explicitly.

Did that choice help during production?

WHIT: It didn't hurt us. It was helpful for production because we weren't specifically doing period, so that freed people up not to go crazy with things. It was the guiding principal to make it seem past.

How would you define the theme of Metropolitan?

WHIT: I can't nail down themes. It gets me in trouble now when people ask me about my new script. Unfortunately, I answer when I should say, "Well, I don't know. Draw your own conclusions."

How did you know when you were done with the script?

WHIT: That's odd. It happened faster than I thought -- that sounds funny for a four-year project! I thought it was interminable, I thought it would never end. And suddenly it seemed like, whoa, we're ending. This is it. This is the film. And so it was a bit of a surprise.

I find that generally happens in an interminable scriptwriting process suddenly you're close to the end or at the end before you even thought it was possible.

What's your writing schedule?

WHIT: Well, it changed completely from the Metropolitan period to subsequently, because at the time of Metropolitan I had a day job, and so I would have dinner and I'd go back to writing after dinner. So I was drinking coffee late at night and often I would be at the computer at 1:00 am, really dreamy and half-awake and my mind wandering into dreams and I'd usually keep at it until 2:00. So it was a very strange process writing from 11:00 pm until 2:00.

Was there anything you learned writing Metropolitan that you still use today?

WHIT: Pretty much everything. I changed the time of day, but everything else is pretty much the same as that process. I still don't use the screenwriting programs and cheat a little bit on the formatting, so it doesn't look as long.

What was it like to get an Academy Award nomination for Metropolitan?

WHIT: I have to confess that I was always terribly, terribly anti-Academy Awards -- until I got nominated for one. But as a want-to-be or not-yet-successful filmmaker, there's something terribly disheartening about that spectacle. But then you're nominated and -- it's great, even losing.

Virtually the entire cast came and, with Line Producer Brian Greenbaum as ring-leader, we had a blast. But after I quickly reverted to anti-Oscars mode (the exception being 1995, when Mira Sorvino won hers and a lot of films I loved were nominated).

So many interesting, likable and sometimes great films are getting no -- or next to no -- coverage on their theatrical release, while madly-expensive campaigns and over-the-top coverage is devoted to a handful of films (and not normally the ones I'd most like). It just seems to get more and more extreme and disconnected from the honest pleasure of going to the movies and discovering ones you like.

I now get a sort of early winter depression from the screeners Academy members are sent. You feel obliged to watch a lot of them, but very often they are not the films you'd ever go to see on your own and you end up seeing so many images you wish you never knew about. I can't believe that so many intelligent film journalists get caught up in covering this horse race -- which must lead to an abdication of coverage for many untrumpeted releases.

The modern age's motto in the arts seems to be: "More recognition, less achievement." So many of the great cinema milestones date from the thirty years before there were film festivals or highly-touted awards (such as the Oscars at their start). It'd be fascinating to see what a three-year awards and festivals hiatus might be like. Or at least to stop, or sharply tone down, the campaigning for awards.

Did you use any tools to get yourself up to speed as a screenwriter?

WHIT: It was terribly helpful that I found a version of The Big Chill screenplay, in screenplay format. One publisher had the wise idea of issuing a screenplay-size edition of various screenplays, including The Big Chill. I used that to crib format from, to try to get close to film format. And it was actually a good script to have around, because it's an ensemble piece. And the She's Gotta Have It production book that Spike Lee did was very helpful.

And there's a book called The Craft of the Screenwriter by John Brady which has interviews with people like Ernest Lehman and Paul Shrader. I found that a very helpful book. I thought it was terrific.

Dying to make a feature? Learn from the pros!

"We never put out an actual textbook for the Corman School of Filmmaking, but if we did, it would be Fast, Cheap and Under Control."

Roger Corman, Producer

★★★★★

It’s like taking a Master Class in moviemaking…all in one book!

Jonathan Demme: The value of cameos

John Sayles: Writing to your resources

Peter Bogdanovich: Long, continuous takes

John Cassavetes: Re-Shoots

Steven Soderbergh: Rehearsals

George Romero: Casting

Kevin Smith: Skipping film school

Jon Favreau: Creating an emotional connection

Richard Linklater: Poverty breeds creativity

David Lynch: Kill your darlings

Ron Howard: Pre-production planning

John Carpenter: Going low-tech

Robert Rodriguez: Sound thinking

And more!

Write Your Screenplay with the Help of Top Screenwriters!

It’s like taking a Master Class in screenwriting … all in one book!

Discover the pitfalls of writing to fit a budget from screenwriters who have successfully navigated these waters already. Learn from their mistakes and improve your script with their expert advice.

"I wish I'd read this book before I made Re-Animator."

Stuart Gordon, Director, Re-Animator, Castle Freak, From Beyond

John Gaspard has directed half a dozen low-budget features, as well as written for TV, movies, novels and the stage.

The book covers (among other topics):

Academy-Award Winner Dan Futterman (“Capote”) on writing real stories

Tom DiCillio (“Living In Oblivion”) on turning a short into a feature

Kasi Lemmons (“Eve’s Bayou”) on writing for a different time period

George Romero (“Martin”) on writing horror on a budget

Rebecca Miller (“Personal Velocity”) on adapting short stories

Stuart Gordon (“Re-Animator”) on adaptations

Academy-Award Nominee Whit Stillman (“Metropolitan”) on cheap ways to make it look expensive

Miranda July (“Me and You and Everyone We Know”) on making your writing spontaneous

Alex Cox (“Repo Man”) on scaling the script to meet a budget

Joan Micklin Silver (“Hester Street”) on writing history on a budget

Bob Clark (“Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things”) on mixing humor and horror

Amy Holden Jones (“Love Letters”) on writing romance on a budget

Henry Jaglom (“Venice/Venice”) on mixing improvisation with scripting

L.M. Kit Carson (“Paris, Texas”) on re-writing while shooting

Academy-Award Winner Kenneth Lonergan (“You Can Count on Me”) on script editing

Roger Nygard (“Suckers”) on mixing genres

This is the book for anyone who’s serious about writing a screenplay that can get produced!