What was your filmmaking background before setting out to make "Black Smoke Rising"?

DREW: Black Smoke Rising is my third feature as writer/director/producer. The previous one was Monk3ys, an odd melange of Big Brother, SAW, some nasty whisky and the perennially funny situation of a grown man yet to have lost his virginity! It's a micro-budget containment thriller that riffs on the world of reality television, found footage movies and the sorry state of the film industry.

It's also an experimental and weird entity that actually scooped the Raindance Festival award for best microbudget film.

Before that was Umbrage: The First Vampire featuring Doug 'Pinhead' Bradley as an antiques dealer, stuck in the arse end of nowhere, who has to contend with demonic and vampiric grudges as well as the melodrama of his heavily pregnant wife and petulant step-daughter.

Before that I cut my teeth on shorts, music promos, corporate crap and even some food television.

Before that I didn't know whether to be a writer, a photographer or a musician, and kind of thought that filmmaking was a good compromise!

What was the genesis of the project and what was the writing process like?

DREW: This film really shouldn't be. It just shouldn't. I lost my brother in 2010, so it was born from that loss. That grief.

Monk3ys actually was a fresher wound, and has a lot of anger in it that came from that chapter of my life. Black Smoke Rising was written a little later, and was a cathartic experience to write, and to film.

There's not a lot of biography in the film, but there is a lot of me. I shouldn't admit that, but I can't help but be honest about it. As is often the case with me, the writing was not a tortuous process. The story here is fairly vanilla in terms of a hero's journey. The protagonist resists the call, then answers it, has help from a mentor or two along the way, and learns a lesson in the end. I wanted it to be a familiar structure and a positive message. It's a highly emotional journey and there are some particularly emotive scenes that had me pounding the keyboard through a haze of misty grief. I'm just thrilled that James Fisher did such a wonderful job of re-interpreting my personal rants!

Can you talk about how you raised your budget and your financial plan for recouping your costs?

DREW: There's not a lot to talk about here.

The film was shot on a shoestring by the small group of loyal and wonderful friends and brothers that I have in this crazy filmmaking trip. I'm so grateful to all of them, and thrilled that somehow I've elicited this kind of fraternity in such giving people.

What few things we needed, in terms of subsistence, accommodation, insurance and so on - I paid for out of a small inheritance. As I said - in an ideal world this film would not exist - but it does because of the people around me and especially because of all that my brother gave to me - not just financially, but personally too.

I could say that I just want people to see the film and to feel it. If it makes a little money then great. In reality we are looking very seriously at how dead the DVD market is to films of this stature and looking to explore alternative means of distribution. The digital age is consuming us, not the other way around, so we need to be making our offerings as palatable as possible.

Why did you decide to shoot in black and white and what's the upside and downside of that choice?

DREW: Both myself and Glen Warrillow, the DOP on the film, are avid lovers of monochrome. There is just such simple beauty in seeing the full colour world in terms of tone rather than colour. I think it is a lost art, and that a lot of people just decolourise things and think that's enough. It's not. It's so liberating to get to the point where you 'see' in light and dark.

Aside from that, there are a couple of reasons for the film being in black and white. First up I like the sense of 'vintage' that it brings. I think it sits with the road trip, with the blues music, with a few noir sensibilities that I love.

Also, the film is a study of grief. It is a world without colour. Grief is such a powerful and horrible beast of an emotion that it can utterly consume you and affect every facet of the world and how you see what is around you. There is nothing else. It IS monochrome.

Honestly, I don't see upsides or downsides to the choice. It is what it is. There are moments when I thought we'd inadvertently found some wonderful combinations of colour that nobody would ever see, accidents of production design, but that's hardly a downside. It really just affects the way you work. It affects the way you light scenes, especially when you start veering towards noir. We even created a gobo at one point, which is something rare these days, and a real staple of noir.

What camera did you use and what did you love and hate about it?

DREW: We shot on the Panasonic LUMIX GH2. Everyone else seems to be shooting on Canon 5Ds these days, and I've done that too. Obviously here, we're talking about shooting microbudget stuff on DSLRs - which is so damn feasible now!

I did a fair bit of research and testing and just didn't find the Canon to be what I wanted. The dynamic range of the GH2 suited me better, as did the clarity of the nice lenses that you can get for it. It renders blacks and highlights beautifully. Granted, it suffers a little more in the midrange when you blow it up, and perhaps the full frame and better sensor of the Canon can cope better here - but we were shooting black and white, with highs and lows. I had very little midrange to worry about, so I much preferred the definition that the GH2 gave me.

I normally wouldn't propose shooting too much on DSLRs. I think they just aren't suited for a lot of things. If you want a pull focus you need a hell of a rig, and by the time you add in a monitor, follow focus and all that you may as well use a full on camera. What I love about the GH2 for this kind of film, where I was more concerned with a beautiful photographic frame for the action to move within (as opposed to a constantly moving camera) is that (1) it takes such beautiful photographs, and (2) it is so compact and easy to get in places you just couldn't get a bigger camera, which affords you angles and opportunities you'd never otherwise get.

Hate about it? Nothing. I knew its limitations. I wish the battery lasted better, and I wish now that they had a 3.5mm jack input for a shotgun mic, rather than an odd 2.5mm one. But hey - you can't have everything, right?

Did the movie change much in the editing process, and if so, how?

DREW: Movies always change in the edit, and this one was no exception. There were bits that I knew would be MADE in the edit, bits that had no need for continuity of action but would be effectively a montage of soliloquy!

Did it change profoundly? Not really. The first cut was mercifully way too long, a relief since the script was actually on the short side. I'd shot way more than I needed, and was able to cut almost 20 minutes of stuff, some of that being bits of scenes and some being entire scenes. I also moved a chunk from what was becoming an over long act one into the beginning of a slender act two and reshuffled a couple of things. Being a largely episodic piece this was relatively easy.

The most important thing in any edit is good pacing, and having the ruthlessness to excise favoured segments in pursuit of that pace. Black Smoke Rising is a long way from an action thriller, but in some ways that makes the pacing even harder. It is a slow build of momentum that can only really be created in the edit, no matter what the script says!

What was the smartest thing you did during production? The dumbest?

DREW: Smart? I can't lay claim to anything of the sort! Haha.

Ok... I think on any film set, especially micro-budget ones, there are moments where you just have to improvise. The shit will hit the fan at some point and the measure of the man is how swiftly and successfully you manage to integrate that shit into the seamless fabric of the story you are weaving. There's a scene in the film where the protagonist is contemplating an urn full of his brother's ashes, and wondering what size tupperware pot to decant him into for his trip, since the urn isn't really roadworthy. In the script he just chooses one, and next thing we see is him walking to the car with a pot full of ash.

IN THE SCRIPT - when he returns from his trip without the ashes, the urn is on the kitchen counter where he left it. IN THE FILM, he breaks the urn accidentally earlier on, and when he returns there is no urn (and instead one of my favourite shots where the entire frame is out of focus until he puts his hand where the urn should have been and his hand is suddenly sharp).

This is because our esteemed DOP decided to smash the urn in an act of wanton clumsiness and I was faced with this horrible moment where I had to either (1) panic and lose the plot (2) freak out and try and get a matching prop (3) integrate the DOP's idiocy into a new story element and embrace the dark humour of it! I chose (3)! OK - it wasn't that smart. I tried to say I hadn't done much smart to begin with!

The dumbest? Without a doubt the dumbest thing I personally did was travel to the lake district in early October with just one pair of cheap crappy trainers. They got so wet after half a day of traipsing around the lakes that I was already getting tetchy. When, on a simple shot of a drive by somewhere in the Yorkshire Dales, I decided to inadvertently step knee deep into a camouflaged wet dyke (and I mean that literally!) that signalled the end for those shoes, and those socks. I proceeded to direct the rest of that day barefoot in the moors and dales of a flooded Yorkshire until a suitable shoe-equipped supermarket reared into view hours later. Stupid!!

And, finally, what did you learn from making the film that you have taken to other projects?

DREW: Crikey. It's so hard to pinpoint this kind of thing. Everything is a learning curve. I've learned to consider what footwear is appropriate!

As a director, every time you interact with an actor you learn a bit more about directing. You learn things that you can never really apply, but at the same time you are stockpiling experiences and ways NOT to deal with situations or people. You learn constantly when it's best to trust your instincts. You learn to trust other people. That's a big one - part of the building of the team, of the family. Learning the abilities, and limitations, of the people around you is very useful. For me especially, as a weird kind of perfectionist (I think it's more that I'm a control freak than a perfectionist to be honest!), it is good to know that other people have your back and won't let you down when it matters.

Mostly every time I get on set I re-learn everything, and I am reminded of why I do this. There is nothing quite like making movies...

I used to think that filmmaking could never rival the thrill of being on stage and playing music to an audience. But it can. I'd never show it, but I get palpitations when I know something special is happening on set, and it only adds to the thrill that there's a camera bearing witness to it rather than an audience. Oddly enough it's a thrill that I can only imagine getting from filmmaking (as opposed to on stage).

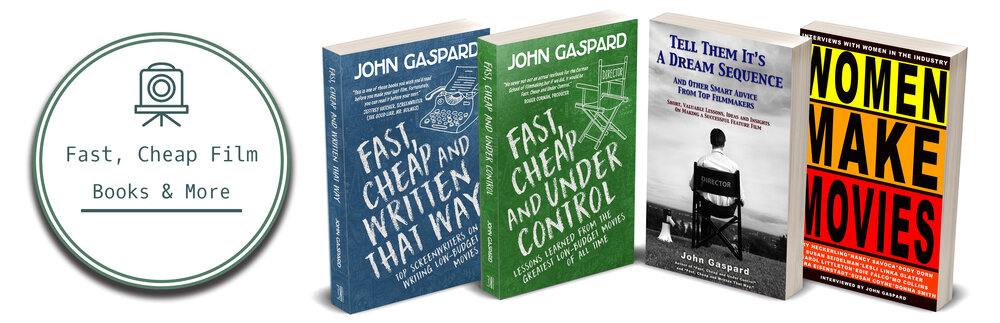

Dying to make a feature? Learn from the pros!

"We never put out an actual textbook for the Corman School of Filmmaking, but if we did, it would be Fast, Cheap and Under Control."

Roger Corman, Producer

★★★★★

It’s like taking a Master Class in moviemaking…all in one book!

Jonathan Demme: The value of cameos

John Sayles: Writing to your resources

Peter Bogdanovich: Long, continuous takes

John Cassavetes: Re-Shoots

Steven Soderbergh: Rehearsals

George Romero: Casting

Kevin Smith: Skipping film school

Jon Favreau: Creating an emotional connection

Richard Linklater: Poverty breeds creativity

David Lynch: Kill your darlings

Ron Howard: Pre-production planning

John Carpenter: Going low-tech

Robert Rodriguez: Sound thinking

And more!

Write Your Screenplay with the Help of Top Screenwriters!

It’s like taking a Master Class in screenwriting … all in one book!

Discover the pitfalls of writing to fit a budget from screenwriters who have successfully navigated these waters already. Learn from their mistakes and improve your script with their expert advice.

"I wish I'd read this book before I made Re-Animator."

Stuart Gordon, Director, Re-Animator, Castle Freak, From Beyond

John Gaspard has directed half a dozen low-budget features, as well as written for TV, movies, novels and the stage.

The book covers (among other topics):

Academy-Award Winner Dan Futterman (“Capote”) on writing real stories

Tom DiCillio (“Living In Oblivion”) on turning a short into a feature

Kasi Lemmons (“Eve’s Bayou”) on writing for a different time period

George Romero (“Martin”) on writing horror on a budget

Rebecca Miller (“Personal Velocity”) on adapting short stories

Stuart Gordon (“Re-Animator”) on adaptations

Academy-Award Nominee Whit Stillman (“Metropolitan”) on cheap ways to make it look expensive

Miranda July (“Me and You and Everyone We Know”) on making your writing spontaneous

Alex Cox (“Repo Man”) on scaling the script to meet a budget

Joan Micklin Silver (“Hester Street”) on writing history on a budget

Bob Clark (“Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things”) on mixing humor and horror

Amy Holden Jones (“Love Letters”) on writing romance on a budget

Henry Jaglom (“Venice/Venice”) on mixing improvisation with scripting

L.M. Kit Carson (“Paris, Texas”) on re-writing while shooting

Academy-Award Winner Kenneth Lonergan (“You Can Count on Me”) on script editing

Roger Nygard (“Suckers”) on mixing genres

This is the book for anyone who’s serious about writing a screenplay that can get produced!