John Gaspard: Today, we're going to talk about your life as an actor and having a diversified pool of things to draw from to be a working actor. I listened to a couple other interviews with you, and there was one point they kept coming to that I wanted to avoid, which was immediately talking about your mother. My connection is, and was, that we went to the same high school, Southwest high school in Minneapolis. So, I thought, well, that's my great connection. And then my friend Jim here, who is … one of the reasons he's here is because he is a working actor as well, but in a much smaller market here in the Twin Cities. So, I thought having him as part of this chat would be interesting. Jim, what is your story?

Jim Meskimen: And he happens to have the name of Cunningham.

Gaspard: Well, we're gonna get to that. Here we go.

Jim Cunningham: Therein lies the story. Your mother made an appearance along with some other famous TV moms at, you know, we're very proud of the fact that Spam is produced here in Minnesota.

Meskimen: That's right. That's right.

Cunningham: And there is a Spam museum. It's that important to us, Minnesotans.

Meskimen: Yes, I know she's been there. We had some Spam swag that she gave us one time.

Cunningham: Well, there, it was from that. She came as a famous mom, along with some other famous TV moms, Barbara Billingsley, and--

Meskimen: And Florence, maybe? Florence Henderson?

Cunningham: I think so. Yeah. Yeah. Right. And I was the emcee of that event and I was interviewing them as they arrived on the red carpet. And I said to your mother, Oh, I'm just so thrilled to meet you because my last name is Cunningham. And more than that, my dad's name is actually Richard Cunningham. And so is my brother.”

Meskimen: Oh, my gosh.

Cunningham: During the height of the Happy Days craze, we literally had to have an unlisted phone number because every third call was, “Is Fonzi there?”

Meskimen: Oh my God. Oh my God.

Cunningham: And your mother said to me, “You have to prove to me that your name is Cunningham.” So I took out my wallet and showed her my driver’s license. And she said, “Oh, you poor darling.” And she gave me a nice hug and a peck on the cheek and it was just, I cherish, I cherish the memory.

Meskimen: That's really sweet. That's hilarious. She challenged you like someone would make that up, you know, so she had to really get to the bottom of that one.

Cunningham: But your mother was just charming and a delight.

Meskimen: That's great.

Cunningham: Yeah. Sorry. We got off on a tangent.

Gaspard: We've given the elephant in the room some peanuts. Now we're shoving it off to the side for you.

Meskimen: Well, if I may say it is, it is no problem at all. I love to talk about my mom. She has blazed such a path for me, not in terms of, you know, any kind of practical nepotism, but just because everyone loves her and loves what she represents. And so I find it very easy to make friends with strangers in this way, because you're already kind of disposed to, well, you must not be such a schmuck, you know, he’s got this mom. And so I'm always very happy to talk about her. She's a delight and she's 93. She lives very close by and she's very happy in enjoying her retirement.

Gaspard: Excellent. All right. So we want to talk about being a working actor, but before we dive into the acting part, I know when you started out, you were focused maybe more on art and cartooning and that. How did you make the switch from that to acting?

Meskimen: Well, I kept both plates spinning. I studied, I taught myself to cartoon and illustrate, enough to be a professional, you know, not enough to be a super genius, kind of in demand, tremendous demand person. But enough to work. And I did that in New York city. And I had this need to perform. And so, I also did plays, I would do little projects.

I would perform, you know, when I could. When I went to college, I didn't take theater classes, but I would do plays, you know, people would audition. And if there was a guy — I was very good at accents. So, you always needed a funny guy with an accent. Sometimes, you know, I could get the part of the old man, the old French guy or whatever. And that I just was always a few clicks above the rest of my fellows there.

So I really kept both these activities going while I was sorting out which one was gonna be the path. Cause I really honestly wasn't clear on what I'd be doing. And, I felt strong feelings about both, but I didn't feel at that time, I didn't see how I could mesh them together. I didn't see how one was going to be, how I’d have to jettison one completely.

And it took me a while to figure that out. And when I did, it was a big relief and I went, okay, I know why I want to pursue acting. I know what's honorable about it. I know why it's right for me at this time. And so I'm going to go for it. And then I went with full energy towards that, but I always, I mean, I haven't forgotten how to draw or paint and I do it now. I'm older, I'm 62. That was when I was 23.

So at this point in my life, I wouldn't mind sitting home and painting a little bit and being away from everybody. But at the time I felt like I needed a more social existence, a more social career that would have more collaborative aspects.

Cunningham: As you look back on things, do you remember some of the first things that you got that were maybe, you know, of note?

Meskimen: Yeah. I started off, I came to New York and I started a bunch of things all at once. Cuz New York is a great place get started, you know, and start things and be a starter. So I was studying acting and I was studying improv. I had a false start. I went and studied at the Stella Adler school for a while, which was a disaster. And I vectored off of that as fast as I could. And I got into improv, which was much more suited to my temperament and I think is better training in general.

So I was doing that. I was looking for an agent and I was also supporting myself as an illustrator cartoonist in the meantime. So I didn't have to be a waiter. I could have a pretty decent job.

So the first things I got had to do with my ability to do impressions. And be a voice actor. So my improv group that I was in had a gig weekly doing what was then a regular feature of the old McNeil Lehrer report, if you ever remember that show?

Gaspard: Oh yeah.

Meskimen: The McNeil Lehrer report, which was a news show. It was like a hard news show, but it had a funny section every Friday. They would take the political cartoons of the day and just by kind of zooming in and out and changing panels, they would sort of, you know, semi-animate them statically. And they would add voices to it.

And then they hired us to do the voices of, you know, Boris Yeltsin, then Reagan and whatever was happening on the time. And we’d go in every Friday. It was my first AFTRA a job and I think I made $114 bucks a week, but it was $114 bucks a week, you know, back then when a ride on the subway was 50 cents.

That was like, this is okay. So that was a nice, kinda like, oh, that's a stability, you know? Cause I think I did, we did a whole, I don’t know, a season or more of it. And every week, you know, it was kind of cool.

My biggest breakthrough came in the area of on-camera commercials. And I had remembered that my mom, when she was a single mom, she would, every now and then before Happy Days, she would get guest spots on things like Mannix and Mission Impossible and Hawaii-5-0. But those were pretty few and far between. And then, if she booked a commercial, it was like, oh, you know, thank God because it would generate enough income, through residuals for her.

And back then commercials paid very, very well. Today it's more rare, as you know Jim. It's kind of a disappearing thing, as things go on the internet. But a network commercial back then could help you stay alive. So, I had that in my mind. I was like, you know, I need to get into commercials.

So, I auditioned and eventually, after a couple of years, actually two years at least going on a lot of things as a young man, I started to get into commercials.

And there was one very, very lucky day that changed my life completely. And it had everything to do with whatever else I was studying, because I was studying communication at that time. I was studying improv at that time and those things came together in a beautiful way.

I had an audition for a grocery chain out of Texas called Skaggs Alpha Beta, the euphonious name of Skaggs Alpha Beta.

And they were looking for a spokesman to interview people in the store. And they had had some market research that told 'em that, you know, you call yourself the friendliest place in town, but you're not so friendly. So, they wanted a friendly spokesman who could talk to people, actual real people and have fun and whatever, you know, and be clean and not insult people.

And that was what I had been studying in improv, you know, clean comedy. Supportive comedy, you know, not cutting the legs off of people. So, I got this audition. I went physically and did it and they said, “oh yeah, yeah, that's great. We're gonna hire you.” I'm like, great. It's three commercials and three regional commercials, which is not a huge deal, but for me it was like, well, this is great.

Then after we did those three commercials, they came back about a month later and said, “all right, we want you to be our spokesman to do all our stuff all year long. We'll give you a contract, radio, TV, photo, you know, put you in the newspaper, the little circulars and billboards and what have you.”

And it was like, forty grand. And I'm like, oh my God, I didn't even know this existed. My mom never had anything like this. This is like new territory. Well, I did that for five years for that company. And every year, the price went up, the contract got sweeter. By the end of it. I was making, you know, hundreds of thousands of dollars a year just on that job, which would take about seven days a year to do.

And that changed my life, because it gave me tremendous confidence, because I created all the material, I improvised every second of it. Maybe not every second, but you know. And it gave me the wherewithal to exist in New York comfortably without having to really sweat the day job and to do plays and to do things that, you know, if you have time, you go and you do improv shows and you don't worry about, am I making any money? You don't sweat it.

And then I actually got known because the footage, I would take the footage and I would cut it into reels and I would send that around and I got more spokesman jobs. So, you know, it was like a side business that sort of developed outta nowhere.

Off of one audition. Sometimes it makes me scared to think: what if I was late? What if I didn't make it that audition, life would be so different.

Cunningham: Somewhere in the multiverse, that's happening.

Meskimen: That poor sucker in the multiverse but he probably has all my hair. So it's fine.

Cunningham: Did you do any Happy Days with your mom? I was just thinking as a young kid, did you do any? You know, walk-ons or extra work on any of the shows your mom was doing?

Meskimen: No. The only time when she became Marion Cunningham—your pseudo mom—she got me into an episode and my sister, not the same episode. She exercised a little bit, you know, and it happens to be one of the most famous episodes of Happy Days that I was in.

I'm a young man, 17, on the beach looking buff. And I come and announce the fact that they've caught a shark out in the water. And then the rest of the show is about how Fonzi’s going to jump the shark.

Gaspard: But it sounds like growing up, that you learned the life of a working actor because you've lived with a working actor, is that safe to say?

Meskimen: A hundred percent.

I think one of my primary advantages in my life has been that I saw what it is, you know, and what it isn't. And I saw it. My mom also was particularly driven and also focused and intent, you know. She's a high achiever. So, whereas a lot of actors go, well, I'm waiting for my agent to call and I don't know, I can't do anything, you know, until they give me an audition. Maybe I can, blah, blah, blah.

And I realized that's like a losing attitude. Because what I saw was a woman who went, Hmm, uh, who can I call? What can I do? Who must I reach out to? Who must I meet? Should I do a play? Absolutely, I should do a play and I should let everybody know that I'm doing this play. And even though it's a crappy play and I'm getting no money, I'm gonna do it.

And I looked at that and went, okay. I see. You need to promote yourself. She hired a PR person. She always had a PR person and would utilize that in any way that she could. And then, how do you live and raise kids and pursue this weird career that is so herky jerky, what do you do? And I saw how she did it. She would economize and we hired out—she always remembers this—we rented out one of the bedrooms in our house. Mind you, we have three bedrooms.

We hired out a third of our house to a college student, because, you know, that was 60 bucks a month or something she would get and shared a kitchen with this person. And, she would do plays and she would volunteer for things and she would push it along, push it down the road.

I remember vividly seeing her rehearse lines for an audition over the sink. We were getting ready to have dinner or lunch or something. And she's going to take off in a minute in the car and drive to Hollywood and do this audition. You juggle, but she was a hustler, in the sense of a hard worker. She was a depression child and I think that came as just part of the territory back then.

But even more than other people her age that I observed, she was just intent. And it came from this vision that she had of as a girl of seeing her name on a marque and changing her name too—so it would look better—and just being like, I'm gonna do this. Which I recognize now from my life experiences and for my own philosophy that it's a very smart way to go about it.

Gaspard: Yeah, it really is. You know, it's interesting in looking at your career and then looking at my friend, Mr. Cunningham here, who I've known for 30 some odd years.

Meskimen: Oh, wow.

Gaspard: And seeing that you both have a very similar mindset when it comes to not saying no to things. I learned that from Jim. Don't necessarily say no to something right away. Listen to what it is. A lot of times you're gonna accept stuff just because you're not doing anything else and why not. And you never know where it's going to lead. You both have this living in sort of a limbo world of: I don't know what's coming next, but because you've said yes so often, and because you're easy to work with and because you bring the goods and because you have so many different threads, there's almost always something coming in. Because you've just kept the streams open. And that's why I wanted Jim to meet Jim, because you both represent the same thing just in different towns.

Meskimen: Soul brothers!

Cunningham: Exactly. Well, I'd like to think.

Gaspard: But now you have an online course to help actors become working actors. Because there's a real difference between an actor and a working actor. I’m in the low budget movie world and there's a difference between being a screenwriter and a screenwriter who's working or being a director and being a director. You can say your thing, but to actually be working at it on an ongoing basis, doesn't necessarily just happen. And it sounds like in your course, you're going to walk people through that process.

Meskimen: Yeah, I've really tried to do that. That's exactly right. You can break down a career, and I'm sure Jim understands this very well, like you have the production side of things, which is the rehearsing, showing up, acting, great.

And everybody's focused on that. You're like, that's what acting is. Well, that's right. That is one sliver of the job. The other sliver is marketing. There's also a kind of a sliver that's having the big goal and the vision and sort of the planning and being the visionary of the organization, because you're an organization. There’s finance, there's paying bills, there's keeping one's self fit, medical things. There's a lot of different moving parts to it.

And, and most of us think of acting as like, oh yes, there I am on the stage holding the skull. Giving the speech to Yoric. Okay, that may happen, that may be part of it, but that's like an eighth of it or a 15th of it. So, in my course, I've tried to share what those other parts of the organization that I do.

Because I was paying attention, thank God. It didn't just happen by luck. It happened very concertedly and very determinately. So I know what we did. And I say we: I've got a little team of people, with my wife and now my daughter helps me, agents, managers, other people to actually keep it rolling, because it is that kind of life, the freelance life.

And there are many different kinds of freelancing lives that people can lead. But in an actor freelance life, you don't know the next week. Like, I looked on my calendar yesterday. And I went, wow, there's a lot of blank space on that calendar. And yet there is no blank space in, you know, my bills summary--I'm going to have to pay whether there's something or not.

So now today, because of all the promotion that I do during the week, now I have a couple jobs. I never sweat it because—probably like Mr. Cunningham—I know that these are the actions that I have to do. I know that schedule's gonna fill out. It's gonna fill out ahead of me almost like a train track rolling out in front of the steam engine.

So, in the course, yeah, I've composed a bunch of different videos where I talk about certain things about auditioning, about promotion, marketing, and other very important aspects of keeping the career rolling. I don't teach acting. I'm not going to go there. My wife has a wonderful acting school and anybody can check that of out if they want to. It's called The Acting Center and they run online courses as well as in-person here in LA.

I'm not teaching anything, but I'm sharing. What did I do? And what have I found after 35 years of doing this are the important steps to take, the important actions to always keep in, and what might happen, and how I've bobbed and weaved and kept things going so that I didn't have to take another job.

I never had to back up and go, well, I retreat, you know, now I'm gonna go and just go into teaching or now I'm gonna go into, you know, real estate or nothing wrong with that. And I know a lot of actors have done it, but I have not had to. And I'm a little bit stubborn at this point. I'll go kicking and screaming into any other, non-artistic field.

Gaspard: Good for you. Without giving away too much of the course, we’ve got a couple questions that I'm always interested in when it comes to this sort of career. What's the biggest mistake that beginning actors often make?

Meskimen: I think the biggest single mistake is to have the right mindset concerning who is creating the career. Because we come seemingly with hat in hand, as actors, to the audition, to the theater, to meetings, interviews, we can fall into the trap of thinking, I'm waiting for someone to give me something. When we're really desperate, we're really like beggars and it can get pretty bad. And as any actor who's been begging knows, it just doesn't work very well. It's very unattractive. Unless they're hiring a beggar. For the role of the beggar, you know, then it's okay.

All other times it's really anathema. So, I think it's a viewpoint of like, I am gonna create this career. That's what I saw my mom do. And that's what I exercised too. I totally mobilized that, because I'm a creative person, I like to create. So, it was kind of like, well, here's a good excuse: You want an excuse to create? Guess what? Your whole career is up to you.

What you wanna do, what you're good at? How much you pursue it, how well you do, how fast you go, how much you get paid. It's really kind of up to you. And that may seem counterintuitive or stupid, or, you know, bewildering to people as they just start out, because we are looking to collaborate. We are looking to fill a hole that someone else has created.

You know, somebody is out there right now, writing a part in a show that will need to be cast. And the casting director will be looking around for that person. That hole didn't exist until that writer came up with it. So, in a way, they have created that, they've created that opportunity, that position that needs to be filled. But we can always sort of be ready for those things.

I believe in sort of deciding and picturing things and putting things out there in the universe. So, I do that sometimes I'll go, you know, somewhere someone is writing a great part for me and, it's very difficult to actually link that to cause and effect. But the fact is I've been working as I said for a long time.

So, I think it's just a mindset of: you have to take the hat out of your hand, put the hat on your head or on a hook and go, you know what? I am the guy in charge. So, how much money do I wanna make? What do I wanna do this year? Take charge. Don't go, well, I hope, if only, well, maybe if things go well, somebody might possibly grant me…

No, no, no. That's a losing attitude. That's an expectation, you know, and being the effect of something rather than actually trying to cause something. So, it's a hard lesson to tell people, because so much of life is sort of dictating that we behave like people that are created upon. You know, we are marketed at, you know, come and watch this movie, sit in the dark while we tell you a story and feel this way and laugh at this part and, you know, and pay this money and, oh, okay.

We get that all day long. There's stuff, just shooting at us all day long and at some point, the artist has to kind of shake it off and go, what do I wanna make? I'm gonna make it, you know, I'm gonna produce it, I'm gonna create it.

And so that's what I think is the biggest change. The biggest mistake that could just go through a whole lifetime or a whole career of a person is like, they're thinking like, God, the agent will give me the thing. And then I might, if I possibly do well, they will give me the part and then maybe they'll keep all of it in and not edit out all of it.

And, and then maybe they will pay me and you know, all this kind of awful , you know, slave kind of mentality. As much as you can turn that around. You'll notice that the very big actors didn't take no for an answer. They developed their own projects. They were fussy. Sometimes they were saying, I won't do that, but I'll do this, you know.

They're demanding on themselves and, and many of them have created their own things. I always think about Billy Bob Thornton, would Billy Bob Thornton have the terrific career he does today? He's a great actor, but do you have the career that he has today if he hadn't decided, man, I'm gonna write this script and star in this Sling Blade thing myself.

I don't know. I doubt it. And there's lots of examples of people like that, because he wanted to do it, cuz it was something he observed in life or had this idea, I think while he was on another shoot and he turned, you know, the material of his life into this project that he believed in and miracles happened. And a lot of stories like that.

Gaspard: So you had the advantage of growing up, watching a working actor. So you had probably a bit better sense of that world than someone coming in from the outside doing it. But was there anything that you were surprised by once you started being a full-time working actor?

Meskimen: One lesson that I learned very quickly was: I probably would've had a commercial career about two years earlier, but I made a mistake. A strategic error.

There's a lot of potency to beginner's luck in show business. We hear a lot of stories. They're almost like legendary stories about people who went well, you know, I wasn't, I didn't even have the audition. I went with my buddy and my buddy didn't get the job. And I did. And you hear that there are gazillion stories like this.

Right? Same thing happened to me. I went with my friend to visit a girl who was working for Barbara Shapiro casting in Manhattan. And I went to say hello to this girl. And she said, “oh, by the way, you know, we're casting for this beer commercial.” So I got a call back. I got a second callback.

I got a third callback and they pay you for the third callback. But in between the second and third callback is where I made my error. This is funny, because it was related to impressions and impressions has always been a door opener for me. It was a Miller beer commercial with guys sitting around at campfire.

And I went well, I'm playing a guy who stands up and does a John Wayne thing. That was me. They kept calling me back, kept calling me. And then I had some stupid conversation with the girl that I had been going out with at the time. And she said, “why don’t you do Henry Fonda?” And I went, “yeah, I'll do Henry Fonda.”

That was the end of that. So the lesson I learned is a very important lesson. Most actors pick this up very quickly, but I just kind of screwed up. It’s that if they keep calling you back, don't change anything. It's going right.

If they ask you on the day: Okay, we saw your John Wayne. I wonder, can you do any other voices? That would've been the perfect time to whip out your Henry Fonda, as they say. But I screwed that up. Two years before I got another really good opportunity. So, I never change anything now. I learned that lesson very quickly.

When I did finally book a commercial, I had gone in and I got a call back and I remembered on the day I had like a headache. The day I did the first audition, I was cranky. And on the day I got the call back, I'm like that day, I'm like, well, I feel great. Well, I'm not gonna act like I feel great. I'm gonna be cranky.

And I went in and I booked that job. By applying this do not change anything.

Cunningham: Smart. A lot of people don't think that through, boy. That's a really good tip. If you're an actor listening, that's the price right there. You just got gold just dumped right into your lap.

Meskimen: Yeah, it would be like, if you went to a restaurant and you had the halibut one time and you go, oh my God, this halibut's great. I'm gonna come back. And if they serve you the halibut and now it's in a totally different sauce. You're like, what the fuck? I came for the halibut. What happened?

Cunningham: What happened? As you think about, you know, actors like me, can you point to some, you know, sort of generic, “Hey, this is here's another trap don't fall into this one?” Something that you see other actors kind of making that mistake again and again?

Meskimen: Sure. And it's related to my first comment about what's the biggest challenge in changing this mindset of who's in charge and being in the driver's seat, if you will, of your career. And I think I wind up talking to a lot of people, particularly guys our age who maybe have not made their peace with social media.

But for me it was a major breakthrough to finally have the discipline to get onto YouTube and begin what has become the last 11 years of really, just an interesting chapter of my life, where I have something that I would've loved to have in New York, which is this access and ease of production.

Anyway. Not to talk too much about myself, but just the fact that most actors are underutilizing, I think, the technological reality of today, of being able to share performances with the world and to generate interest in what you do. And to also creatively expand and reach out and come up with content yourself that may not at first have any kind of monetary value to you, but as a product, as a promotional activity, is virtually free and can create great windfalls and attention.

Are you doing anything on YouTube or anything?

Cunningham: You know, I'm really not. And not only am I not doing it, but you're the first person to suggest that if you were to use that in some way, that there would be a benefit there. Now, I'm not a great actor. I'm better as myself than I am as anybody else in general.

And that's where the bulk of my work comes is being me in front of a camera, or on stage. The challenge has been thrown down now: what could I do on YouTube? And could that effect, because as you mentioned, as you get older, the opportunities decrease.

They're looking for a 30-year-old, they're looking for a 40-year-old, and I'm not that anymore. I always used to tell people what you want is the number of auditions to go down and the number of jobs you're doing to go up. That's the goal. And now I'm finding that's no longer true for me. It's inverted now.

Meskimen: Yeah. Well, I can speak to a couple of points to that. So, I understand about playing yourself and being like a spokesman or being like something, a character that is more or less how you appear to other people. I would suggest that you're much bigger than that.

You're much more various than that. Your possibilities and potentials as just a human being are far beyond what your body might dictate: how you look and how you think about things, even some ideas you have. I think you're bigger than that as an individual. And one of the things that I love about acting is that one gets to occupy a completely different point of view.

(as Ian McKellen) For example, this is why I do a lot of impressions is because sometimes I can just change into another person and look at things completely different point of view.

That's sort of the magic of it. I mean, the expectation of an actor generally is that they can do different things. You wouldn't buy a Swiss army knife and find that it has one blade and go, I'm really happy now.

You'd go, wait, where are the scissors? Whereas the ballpeen hammer or whatever. To be an actor means I can play a lot of different characters. I can play a lot of different roles. Now, as we get older, maybe, you know, that gets narrower, but we can certainly always push. Push it out. And I think you can surprise yourself by what you're actually able to do.

You've got a lot of wisdom now, you've earned that over the years, you've met a lot of different kinds of people, and I think it's probably something to take a look at. An actor, if you look at the job description, if there is such a thing it's like knowingly taking on another point of view to help tell a story, that's kind of a quick definition of what it would be like.

So if you are facile and ready to occupy other viewpoints, to look at things from the point of view of someone who's, you know, just physically exhausted or someone who's been just kicked around their whole life or someone who's just won the lottery. You know, if we practice this, which is what they do at the acting center, just kind of changing viewpoints and looking at things from different points of view, then you discover that, you know, I can do a lot of different things. Because a human being is like that. A human being can adopt all kinds of different viewpoints and feel all different kinds of ways and express different kinds of emotions.

And there's a great freedom in that. I think you'll blossom if you start to have a little try at that.

Cunningham: I like that. That's good advice. I like it a lot.

Gaspard: You know, it's interesting. You mentioned social media and we're all of a certain age and feel like things might be passing us by, but Jim Meskimen, your use of social media, your use of YouTube—I found you on TikTok—your promotion of yourself does not seem like promotion. It does not seem like marketing. It is just you, having fun, doing the things you do. And then in some cases it's impressions. It's other cases, it's you doing characters that you've created. And I think that's sort of the secret to promoting yourself on social media is: Do what you love and eventually people will find that and want to be part of that.

Meskimen: Yeah. And there's an example. Thank you for noticing that. I appreciate it. And I'm having the best time. Two things I wanna say about that. one is: I don’t know if you've ever heard the entrepreneur, Gary Vaynerchuk?

He said something very, very helpful about branding. Because branding, when we talk about branding, it immediately sounds like something we don't wanna have anything to do with. But branding is reputation. That's another good synonym, your reputation. And we prove our reputation all the time. By how we talk to people, what we do, what choices we make, it's pretty simple.

So if we let people know, Hey, I was at this concert and I had a great time. Well, we know that about you. We know that you love Fleetwood Mac, you know, and that you had a great time on last Wednesday. That is your reputation too. If you create a character or you go to a play or you just say, God, you know, this is on my mind and I have to say something about it. That's your reputation too. That's your brand. People get to know you that way.

And the other point I wanted make was in terms of the volume of what I do and how it doesn't seem like branding. It's just me having fun. And that is indeed entirely what it is.

There was a guy when I was kicking around New York, back in my twenties, in various subway hubs, like grand central station or times square in the subway downstairs. Every now and then I would walk past this young man who was a drummer and he was banging on—not drums—he had like a joint compound bucket. And he had, I swear, I remember one time he had crisper from refrigerator—you know, the shelf, the drawer.

Anyway, he was banging away those buckets and those instruments, which obviously did not cost a lot of money. And the sound just racketed through the subway. And it sort of integrated; when you walked through to that drum beat. You were kinda like, yeah, I'm in New York and I'm walking.

Not for nothing, this is the right soundtrack for this little part of my life right now, you know? And how many people would walk by this guy every day? Was in the hundreds of thousands, probably, right? So, there is a guy—this is a great example, if you think about it in terms of social media—this was a guy who was drumming for a massive audience every day.

And were people giving him money? I never gave him a dime. I mean, he couldn't have made more than, I don't know, 75 bucks a day. Who knows, maybe made more than that. But that wasn't the point. The point was 10 years later maybe, or earlier, there was a production, called, Bring in the Noise, Bring in the Funk.

This guy got hired. He was seen by the director. He was in a Broadway show. He was performing seven nights a week. I can guarantee he wasn't making $75 a day. And it just was like: oh, look at that. That's a great, very easy example of like, okay, this is what obviously he loved to do it.

Nobody said here is the way to the Broadway: Get your bucket of joint compound young man. And go thee to Times Square. No, not a chance. He loved rhythm. But he made it go right. And I don’t know where he is today. I don't even know the guy's name, but I know that it was the big start of something with tremendous potential for him, you know.

Gaspard: Follow your bliss. Like they say, you never know. I have two working actors in front of me right now. Tell me about rejection and dealing with rejection and how you deal with rejection

Meskimen: Oh, good question. Yeah. Rejection is like a kind of a shock to the beginner, because we kind of know it's coming, but it still hurts.

And the fact is that it's something that you have to kind of make friends with, which sounds really, really impossible. I just watched a video of a guy who—I think it was Joe Rogan. I watched a little on TikTok. Joe Rogan was talking about this ice-cold bath. That you know, it's now a thing to do these super cold plunges to try to handle inflammation in the body.

And I watched him because I want to see you go in that bath. And he went in. I'm like, how long is he going to stay in that thing? It's 34 degrees, just above freezing, but he was in there. I lost interest. So he went on for minutes and minutes. And being judged and being rejected is like that cold bath.

Now, Joe Rogan said that the first time he went in that bath, he could do it for about a minute. And then he got the hell out of there and went into a sauna. Probably. Now he can go in for 15 minutes. So, it was like that for me with rejection. Because, you know, you prepare something it's—and when you're an actor, it's different than other jobs. Because other jobs, if you're producing, like, even a piece of artwork, you know, it's exterior to you.

It's not you. It's that piece of paper. It's that object that you've created. With an acting job, it's like, oh, it's your hair, your body, your face, your tone of voice, your presence, your smell. It's all what you're offering, you know, whether you want to or not, it's there. Especially in the pre-Zoom days.

So, the levels and the dynamics of you being judged are just exponential. You know, you're like, wow, oh, you didn't like it the way I sat, you didn't like the way I said that one word, you know. There's all these swords to die on. But if you recognize and get familiar with the procedure, then after a while, that bite that it had originally does start to taper off.

And at this point— and early on for me, I'd done hundreds of auditions—I'm like, some I get, some I don’t get. Unless somebody says something really cruel, which is a whole different category of thing. There is just a natural judgment and evaluation. That is part and parcel of being an actor, where they go, “thank you very much.”

And you never hear from them again and you go, wow, that's one thing. If someone says, “yeah, you know, you're not quite right. You're not quite good enough. Boy, we were really expecting something better or, wow, that sucked.” I mean, there's a whole range of othernesses. Then that that is something that you don't necessarily get comfortable with.

But after a while you kind of gird your loins and go, well, that comes up, I have a different response to that. You know, I'm gonna say a little something or I'm gonna make a mental note: This casting director is an asshole. But that's different. The everyday kind of, “thank you very much for coming in rejection,” that's just something that if you do it enough and if you're not too precious about it and you don't take it personally, cuz it is not personal, it absolutely is not.

You know, one good thing too is to—if you're an actor and I have not done this, so I'm giving you this advice that's kind of secondhand—but go and participate in a casting process where you're not being cast. Watch other actors come in, be a reader or something, and observe the variety of people that come in and what is attractive and what is unattractive and what is distracting and what is not distracting.

And it'll give you some reality on like, oh, okay. We've interviewed or we've auditioned 15 people for this role, 12 of them could do it. They were fine, but this one's hair is this way. And this one has a little better this and you know, and I don't know, I met this guy before, I'll work with him again.

They're arbitrary, small kind of gentle reasons why the person gets hired. And it's not the Roman arena where they go, Thumbs down. You're dead. Now it’s thumbs down, you are a failure. You—it's your turn to be eliminated. It's not that. It's like, yeah, you're great. You're great. I got nothing to say except the director wanted to work with this guy.

And you’ve got to make your peace with that and go, yep, I would do the same thing if I was a director. I wanna work with this guy. Who cares? It doesn’t matter.

Gaspard: I still remember William H Macy saying once he was on a TV show and went up to the producer/director, the guy in charge, and said, “thanks so much for casting me in this.”

And the guy said, “yeah, it was between you and another 5,000 people, but you’ll work.”

Meskimen: I just found out—this is interesting—I got a role in a show that I'm gonna work on next week. And I was like, wow, great. You always, you know, these days, Jim, you know about this, you do these at home self-tape auditions, and it seems fake. It still seems kinda like I'm not in show business. I'm just doing it in the back of my house, but they call you up and they go, you know what? We want you for the role. And I'm like, oh, okay, great. And I'm all chuffed about it, you know, excited.

And the wardrobe man, when I went to the wardrobe fitting, for reasons of his own I'm sure, told me that, “Yeah, they originally hired another actor to do this part and then the schedule changed and so he couldn't do it.” And so then I found out, you know, in that sort of covert way that I was not the first choice.

I still get to do the job. But that's another aspect of things that could come in and sour things and you can start to feel sort of like a victim a little bit. But you know what? I just look at, what am I trying to do? I'm trying to get bigger and better parts in bigger and better shows. So that like, like Jim said, maybe I don't have to do so many auditions. Maybe they come to you and say, we have an offer. I love that. That happens sometimes, but I am also very happy to audition. I'm very happy to meet with people because for me, I look at an audition is a performance.

Especially these days when they expect a performance. I don't hold the script. I memorize it. I work it out. I spend hours and hours and hours getting that show together and shoot it to the best of my ability, put the best sound on it that I can and fire it back as quickly as I can.

And it's fun for me. I like the activity of acting. I like the activity of portraying a different person, of trying something out.

And that's, that's the joy of it. And the chore of it.

Dying to make a feature? Learn from the pros!

"We never put out an actual textbook for the Corman School of Filmmaking, but if we did, it would be Fast, Cheap and Under Control."

Roger Corman, Producer

★★★★★

It’s like taking a Master Class in moviemaking…all in one book!

Jonathan Demme: The value of cameos

John Sayles: Writing to your resources

Peter Bogdanovich: Long, continuous takes

John Cassavetes: Re-Shoots

Steven Soderbergh: Rehearsals

George Romero: Casting

Kevin Smith: Skipping film school

Jon Favreau: Creating an emotional connection

Richard Linklater: Poverty breeds creativity

David Lynch: Kill your darlings

Ron Howard: Pre-production planning

John Carpenter: Going low-tech

Robert Rodriguez: Sound thinking

And more!

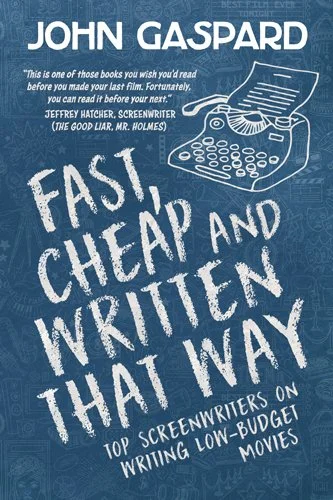

Write Your Screenplay with the Help of Top Screenwriters!

It’s like taking a Master Class in screenwriting … all in one book!

Discover the pitfalls of writing to fit a budget from screenwriters who have successfully navigated these waters already. Learn from their mistakes and improve your script with their expert advice.

"I wish I'd read this book before I made Re-Animator."

Stuart Gordon, Director, Re-Animator, Castle Freak, From Beyond

John Gaspard has directed half a dozen low-budget features, as well as written for TV, movies, novels and the stage.

The book covers (among other topics):

Academy-Award Winner Dan Futterman (“Capote”) on writing real stories

Tom DiCillio (“Living In Oblivion”) on turning a short into a feature

Kasi Lemmons (“Eve’s Bayou”) on writing for a different time period

George Romero (“Martin”) on writing horror on a budget

Rebecca Miller (“Personal Velocity”) on adapting short stories

Stuart Gordon (“Re-Animator”) on adaptations

Academy-Award Nominee Whit Stillman (“Metropolitan”) on cheap ways to make it look expensive

Miranda July (“Me and You and Everyone We Know”) on making your writing spontaneous

Alex Cox (“Repo Man”) on scaling the script to meet a budget

Joan Micklin Silver (“Hester Street”) on writing history on a budget

Bob Clark (“Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things”) on mixing humor and horror

Amy Holden Jones (“Love Letters”) on writing romance on a budget

Henry Jaglom (“Venice/Venice”) on mixing improvisation with scripting

L.M. Kit Carson (“Paris, Texas”) on re-writing while shooting

Academy-Award Winner Kenneth Lonergan (“You Can Count on Me”) on script editing

Roger Nygard (“Suckers”) on mixing genres

This is the book for anyone who’s serious about writing a screenplay that can get produced!