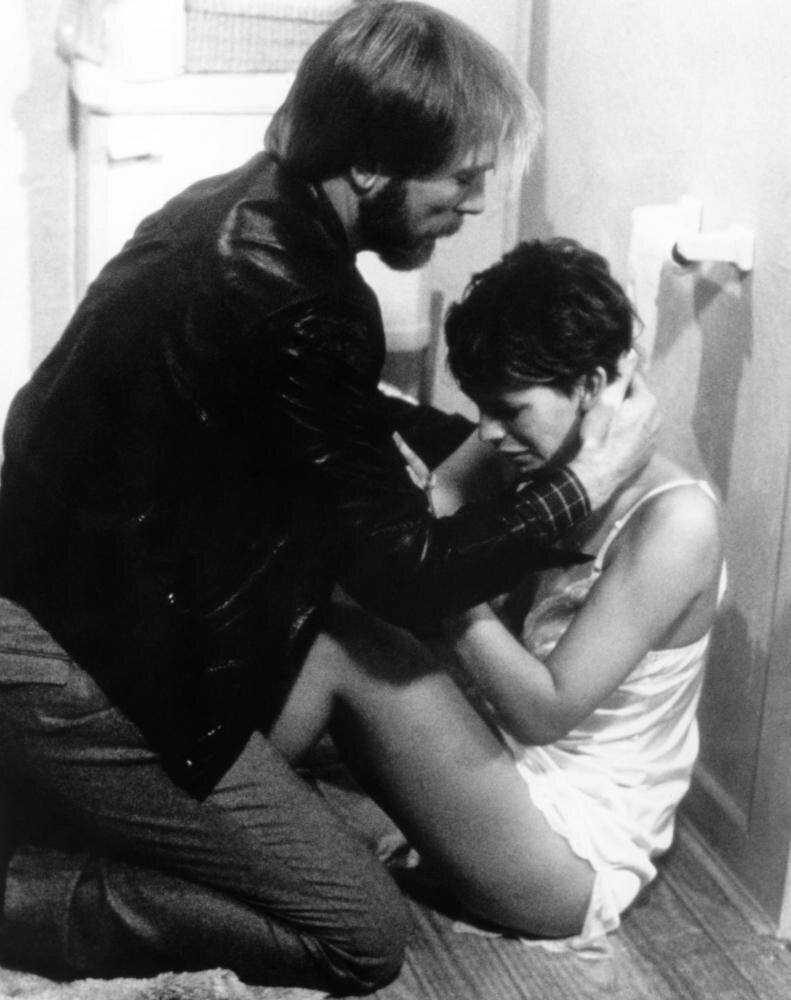

Love Letters is an anomaly: It’s a dramatic, heart-felt, non-exploitative feature produced by, of all people, Roger Corman.

Written and directed by Amy Holden Jones (who would go on to write Mystic Pizza and Indecent Proposal), the film stars Jamie Lee Curtis as a young radio DJ who enters into an affair with an older -- and married -- man.

Give me a snapshot of your background before you wrote and directed Love Letters.

AMY: I was young, for one thing. I had re-written and directed one feature for Roger Corman, Slumber Party Massacre. I had edited several features and had been a documentary filmmaker.

Roger wanted me to do another exploitation film. He also distributed the Fellini pictures and the Truffaut pictures and so he had an art house distribution network. And it was just the beginning of home video and all that money. So, I convinced him that if he made a film for that art house outlet and for home video, that it would make back its money.

I wrote the film on spec. I pitched the idea to him and he agreed to the idea.

His basic theory on low-budget filmmaking is one that I think is still true to this day. He felt you could make a film about just about anything, but there had to be some sort of commercial hook. I could write what he would term an art house movie, what would now be termed a festival movie, but it had to have a saleable quality to it. And by that he meant a degree of humor, sex or violence. Many of the major successful independent films have one of those qualities. Tarantino pictures, for example, have them all.

Love Letters is not a very typical Corman film.

AMY: It's the only art house film he ever made, actually.

How did Slumber Party Massacre come about?

AMY: Well that was kind of interesting. I had come out of documentary films and couldn't make a living in them. In those days, it was not the big scene it is now. I had won the American Film Institute student film festival with a documentary. Martin Scorsese was one of the judges of that festival and he used me as his assistant on Taxi Driver and then introduced me to Corman.

I had no money and I had to make a living, so I became a film editor. I worked for a while as a film editor and was beginning to get successful at it. I realized that if I keep this up, I'm going to be typed as a film editor. I did several smaller movies, one for MGM and a small Hal Ashby movie, and I was going to do E.T. for Spielberg.

I thought, I'll be a film editor unless I make a movie, so I went back to Roger Corman, who I had edited a film for when I was 22 years old. So I went back and said, “What would I have to do to be a director?” And Roger looked at the documentary and it didn't show him enough about what he wanted, because it was an art documentary in a way. He said, “You have to show me that you can do what I do.”

I had never written anything, so I was looking for an existing script. I went into his library of scripts, scripts that he hadn't made, and I took several of them. I read one called Don't Open the Door by Rita Mae Brown. And it had a prolog that was about eight pages long. It had a dialog scene, a suspense scene and an action scene.

I rewrote the scenes somewhat to make it better, and then I got short ends from shooting projects -- my husband was a cinematographer. My neighbor was a soundman. We borrowed some lights, used our own house. I did the special effects, and I got UCLA theater students to act in it.

We spent three days and shot those first eight pages. Then I put them together at night on Joe Dante's system -- he was doing The Howling. I would work at night, after hours, on his Movieola and he gave me some temp music cues.

Then I dropped off this nine-minute reel for Roger that had a dialog scene, a suspense scene and an action/horror scene, to show him that I could do those three different kinds of things which make up an exploitation movie.

He called me up and had me come in and asked me how much it had cost me to do it. And I said it cost about $2,000, which is what it had cost. He said, “You have a future in the business,” and asked me how much I would need to direct the rest of the script. The truth was, I had never read the rest of the script, all I had read was the first eight pages. So I just, out of the air, said “$200,000.” And he said, “Let's do it. You're directing this movie.”

I then finished reading the script and it was a complete mess.

I just took a leap. I called Spielberg and told him the situation and he was kind enough to release me from editing E.T. I rewrote Slumber Party Massacre in about four weeks as I cast it. And, indeed, we made if for $200,000.

What steps did you take to re-write it?

AMY: I rewrote it to be producible. Once you know how little money you have and what the situation is before re-writing it, that focuses your mind -- a lot. You don't go writing scenes at a football game with thousands of extras.

You start to think very logically about what you can do and what amount of time you can do it in. And my background as a film editor and a documentary filmmaker certainly helped.

Did you end up using any of the prolog that you shot on your own?

AMY: No, we never did, because none of the actors were Screen Actors Guild (SAG) and in the end we had to have SAG actors, so we had to toss it, which was too bad. But we didn't really need it, as it turned out.

Where did the story for Love Letters come from?

AMY: My husband and I had written each other love letters. We had been apart after we first met; we met on Taxi Driver. He was the cinematographer and I was Scorsese's assistant. And then we were apart for quite a while. I moved to the West coast and he was on the East coast. So we wrote letters. That was four or five years before.

I had our daughter when I was twenty-six and did Slumber Party Massacre when I was twenty-seven. I was casting around for an idea for an art film and I came upon those letters. And I thought, well this is really interesting. What would happen if our daughter someday read all of our love letters? How would that affect her?

At the same time, I saw a movie called Shoot the Moon, which was about an extramarital affair and the traumas of the married man dealing with his wife and the girlfriend. I thought at the time, man have I seen this a zillion times. Forever I've seen the point of view of the man, torn between his wife and the girlfriend. You see it today in Match Point, for example. It's done over and over and over again.

But I had never seen the story of the girlfriend and what it was like for her. I put that together with the love letters and thought it would be interesting if someone came upon the love letters and realized that their parents had had an extramarital affair; if the love letters were not in fact between her mother and father, as ours were, but between the mother and a lover.

In other words, what would happen if you were confronted with an understanding of a time period in your parents' life which you never really understood -- none of us have a real idea of what our parents were like in their twenties. How would that affect your life? And I thought it would be interesting if that then thrust her into an affair with a married man, trying to replicate what she saw her mother had.

Basically, it was designed to be a movie about what happens to the woman outside of the marriage, who in fiction is usually painted as a terrible villain and often is a victim who gets left in the end.

Were you writing to a specific budget?

AMY: No, but I knew I had to make it inexpensive and one of the cheap ways to do that is a limited number of locations, because every company move takes up an enormous amount of time.

You see this a lot on television today. You have something like ER or The West Wing, where they're wandering around those same halls over and over and over, and they're talking and talking and talking and talking. What they're doing is eating up page count. That is a much faster thing to shoot than it is to shoot activities where people move from place to place.

If there's four different scenes in two pages, you have four company moves, where you have to move the entire company, re-set-up, re-light, re-do everything. And the company move itself takes half the day.

Slumber Party Massacre was all shot between a school and two houses, which were side-by-side. That was it for the locations, so once we had shot the ten pages that took place in the school, we were into those two houses for the rest of the 28-day shoot.

Love Letters had many more locations than that, but basically they were all in Venice. My own house is the main location, so I didn't have to pay for it. We were living in it at the time. So that kept the cost down an awful lot.

Why did you structure the film as a flashback?

AMY: I was doing an art film and unlike most people who seem today to only set out to do art films, I had been working in big commercial movies, like Taxi Driver and the two pictures that I had cut.

I wasn't fancying myself to be Fellini or anything like that. But I went and read all the screenplays of Harold Pinter, believe it or not, because I felt that this would be high art, and there are some great screenplays in book form by Harold Pinter. Probably there was something in there that inspired the flashbacks, would be my guess. It's certainly an overused device now.

It was originally called My Love Letters. One of the big decisions you make in writing a script is point of view. Multiple points of view are more complicated for a novice writer than one person's point of view. So a lot of debut films tend to follow one point of view.

For example, Rushmore. They're often coming-of-age stories or single person stories that have some sort of personal quality. The Squid and the Whale is another good example. You have scenes with the parents without the son there, but it's basically that son's story. The way he views his parents is the sensibility of that movie.

Although you term Love Letters an art film, it’s not a leisurely film. It gets up and running very quickly.

AMY: Well, I was a ruthless editor. I think of all the things I've done, the thing I was best at was as a film editor. That sounds like braggadocio, but what I mean is that I was better at it than I am as a writer or a director. It really suited my sensibility. I like things to move. To this day, I'm always thinking, "Why didn't I lift that out, why didn't I move it along?" I like to take an audience on a journey and go.

I think Love Letters is an interesting early film, compared to stuff I did later. It changed the way I work to a degree, because I came to see that it lacked humor. I don't enjoy many serious, dramatic movies that don't have, occasionally, some humor in them. I find that it can be too lugubrious.

Crash is a good example of a really wonderful, complicated arty, sophisticated movie, but it's also quite funny.

Life is funny, and I think it's a common mistake that people make doing their first features, to just be so terribly serious about themselves or their subject matter.

Well, the main character is clearly depressed and that affects the tone.

AMY: Well, there is that. Her situation was pretty bad. But when you screen it with an audience, you saw that they really enjoyed the scenes with Bud Cort and Amy Madigan a lot, and you realize that an audience really appreciates some relief from it. I mean, Hitchcock knew that: instead of unrelentingly going in one direction, provide some emotional relief.

How much backstory did you create for the characters? In particular, I'm thinking about the relationship between Anna (Jamie Lee) and her father, where there appears to be a lot going on, but it’s not really talked about.

AMY: I did create a lot of backstory for that. Roger Corman made everyone who directed for him take acting lessons, which I had never had even the faintest interest in. He made all the directors who worked for him take acting lessons with a wonderful old teacher, Jeff Corey, who was a blacklisted actor who taught.

I would say those acting lessons are what enabled me to write. I didn't really ever study writing or think about writing or have any interest in writing. I was interested in non-fiction stuff, like documentaries, not fiction. I wasn't interested in theater, wasn't a film buff. But when I took those acting lessons, I discovered that the process that the actor goes through was different from what I thought it was and that it's essentially the same one that a writer goes through.

It's not like you pretend to be the person. You find inside yourself some part of you that could be that person. It could be an axe murderer, but we've all wanted to kill somebody at some point.

And once you do that with every single character, you try to inhabit their skin and then you sort of free-form write from that person's point of view. You're not standing outside that person and thinking, "What would this person say?" It's much better if you are taking the place of that person, trying to feel the sort of things that they would feel, putting yourself into that person's position.

Anna’s relationship with her father was pretty crucial in motivating her to do what she did. Instead of being angry when she found out her mother had an affair, she was relieved for her, because the mother had this loveless marriage. So Anna’s basic feeling was that maybe she should be taking a chance, do something that is not typically considered the right thing to do, because it might be the right thing to do.

Do you start with a theme?

AMY: This is one of the few that I didn't start with a theme. I think I started with the situation and probably anger -- anger's a good place to write from.

I was angry at seeing yet another movie from the husband's point of view, about how tough it was for him when he had an extramarital affair.

That was an era that many people don't remember so much now, but all movies were from the male point of view. And that same anger on my part was partially behind Mystic Pizza, which was the next thing I wrote. At that time there were endless -- and I mean endless -- comedies, coming-of-age stories about a bunch of guys. Every studio did them all the time. It was the most durable genre and no one had ever done it about women.

Mystic Pizza was specifically designed to be my Diner. I hoped to direct it and expected to direct it and wrote if for myself to direct. And it is, in many ways, a female Diner. It's about similar issues.

Did Corman have precise direction on the amount of nudity in the film?

AMY: Yes. He wants sex, violence, or humor. He actually told me that lovemaking wasn't so much required as nudity. And he didn't mind if she could just be lounging around the house nude, but there had to be nudity. He had to have some way to sell the thing.

It's actually the one thing that troubles me about it. I find some of the nudity really gratuitous. But it was the price we paid to get it made.

I was really impressed with the simplicity of the Polaroid scene. It's a lock-down shot, we don't see the couple, we only see each Polaroid photo he takes of her as he drops it into the shot. It said a lot about the relationship, but it was also very cheap to shoot.

AMY: That's one of my favorite scenes. That's a really good example of how you come up with stuff. Writing for a lower budget really focuses your mind. It doesn't necessarily mean that you're sacrificing quality.

I see so many really big budget movies, where they've had everything to spend and have covered everything sixty ways from sideways, but they never did the hard thinking about what was important in the scene. Because they had the time, they just threw spaghetti at the wall and covered everything. As a result, they never thought about what was actually going on.

Another example of writing to a budget was your staging of the funeral scene. Instead of showing the whole funeral, with extras and lighting and all, you put the scene outside the church, after the funeral, which was cheaper to shoot.

AMY: Yes. You don't have to light the interior, it's a simple exterior. And the church that we selected was within a couple miles of all the other locations. So even if the company had to move, it wasn't far. The pool playing scene was shot less than half a mile from that church. And the house she lives in is less than a mile from there. So when we did have to move, we didn't have to go very far.

And when we were at a location, we'd shoot out the whole location. When we were in the back bedroom of the house, we shot everything that takes place there. Then we'd shoot everything that takes place in the living room of the house. You shoot everything that takes place in or around the house, then you move. Moving does eat up the most time.

So you were literally writing for locations you knew you'd be using?

AMY: Yeah, I think writing for locations is a good way to go. I really do.

I remember being conscious when I wrote Mystic Pizza that it would cost more money because there were more locations, that it was a certain type of town. It had one scene that I knew would be very expensive, where there's a drawbridge and a boat.

Did you write the love letters that are read in the script while you wrote the script?

AMY: Yes. They were sort of finessed and re-written. I discovered how audiences pick up narration. They don't understand it unless it's extremely clear and simple. If it's convoluted it's hard to understand when you don't see a person talking at the same time.

Do you show drafts to friends while you're writing?

AMY: It depends on the script. I don't show them partial drafts. I usually do a full draft and it's a very select group of people that I might show it to.

It's a dangerous thing, because not everybody gives good notes and everybody has a different take. There was nobody giving notes on Love Letters, except for Roger saying we needed more nudity. That one was one of the purest of them all.

Usually if I show a script to five people, I will pay a lot of attention to repeating comments. So if three or four of the five people say "The end doesn't work for me," then I know the end doesn't work. If one of the five says "It doesn't work for me," and four of the five say it's fine, then it's less of an issue. You do have to listen to other people's opinions. An awful lot of people fall in love with their own material when they really shouldn't.

More people should get actors together to read their scripts. That's a luxury you get when you're making a movie, you get your table read and you can re-write after that. And you learn so much when you have your first read-through.

I've done a read-through on all the films, except Slumber Party Massacre. It's really useful. And there are actors all over the place who will do it for nothing, who just love to come and perform.

Did you get the cast you had in mind when writing Love Letters?

AMY: No, I didn’t get anybody that I had in mind, except for Amy Madigan. I wasn't necessarily thinking of Jamie. She fell in love with the script, and she was at the time a star, off the Halloween movies.

I think my first choice was Meg Tilly. I was very lucky she fell out, because she was way too soft, really, for the part. Casting is something you kind of learn as you go along with directing. And Jamie was wonderful for it. She's just marvelous in the movie.

James Keach was not at all the first choice. We went to various people and had another actor, who shall remain nameless, who backed out. He was worried about doing a low-budget movie, he was a bigger-name guy who also really responded to the script. He backed out, inexplicably, seven days before we started shooting. He was quite handsome and he and Jamie had really wonderful sexual chemistry. So it was kind of a shame when he backed out. But what can you do?

Keach was a late replacement. It was quite difficult to find a guy at that time period -- and I think it's still difficult today -- to find someone who will work as the second banana in a movie where the leads are women. They don't like that; they like to be the lead.

Did you do any previews of the movie before it was finished?

AMY: No, we did not preview it at all. Roger trusted his own judgment and he was wonderful about it, actually, both for Slumber Party Massacre and Love Letters. He decided I knew what I was doing and he left me alone. I don't think he made any changes at all, maybe a couple little trims here and there. He would take over whole movies from people who didn't know what they were doing. But he liked the movie and he was proud of it.

He opened it in Los Angeles and New York first, and got mixed reviews. He was kind of heartbroken at that. Then somehow, and I don't remember how, Siskel and Ebert got it and reviewed it and gave it a rave. That encouraged him in his own opinion and he gave it a limited release. But truly its life has pretty much been on cassette or on television.

What did you learn on this script that you took to other projects?

AMY: First was not to take myself too seriously and put in more humor.

The other thing was painful at the time and this probably still happens to people. The movie is kind of sincere, and you take a big risk when you do dramas, because if it's not really good or if they're female-driven, reviewers make fun of them. The chick film, the weepie, and so on. They look down on them, whereas I think the equivalent of a chick film for guys is a Bruce Willis action film. It’s equally stupid, it just has testosterone instead of estrogen.

Your heart is on your sleeve a lot with a film like Love Letters. You're pouring yourself into it in a way that's very personal. And when it's attacked it can be very painful in a way that doesn’t really happen with a genre movie. That's a negative lesson, because it can make you afraid to take a chance and that's bad. You have to really learn to take those risks with your heart, I think.

There are several big directors working today who are in the later days of their careers who don't take risks of any kind anymore. They have big budget movies and they are constantly covering themselves in the commerciality of those movies, more than they did in their early work, and not putting inner passion into it. Either the passion is gone or they are too afraid of failure.

You can't really be that afraid of failure. In writing the script and in going forward with it, I think I had a wonderful youthful exuberance that would be hard to duplicate today probably.

Any advice to writers who are working in the low-budget universe?

AMY: Well, it's a different market in this day and age. It's a good era, in a way, for writers starting out on a low-budget project, because you can actually make a movie for almost nothing.

I wish that I'd had the technology that young writers have now, because you can take all kinds of risks without risking all that money, if you are bold enough to write and start shooting.

I think the main thing that is still true today that was true then is that as you write you have to both tap into your heart but you also have to be aware of the very practical side of what it all costs and also what sells. It's an interesting mix.

The world is full of festival movies that never get out or go anywhere. If people are trying to break into Hollywood movies and bigger movies, not make something personal that they're going to put up on the Internet, they have to look at the commerciality of their subject matter. They have to fit what they're trying to say into a framework that is in some form entertaining for people. It has to be meaningful or moving or exciting or funny or dramatic. It can't just be what you'd tell your shrink, you know what I mean?

People perhaps don't realize that at festivals today, where all the agents go and circulate, they're looking for the movie about the couple who are left out to the sharks when they were diving. They're not looking for the next Love Letters, unfortunately.

If you're trying to break into Hollywood, you have to be aware of something commercial in the project. Take a look at some of the things that have sold out of festivals. For example, Hustle & Flow. It's about a pimp. It's about sex. And money. That’s an easy sell.

How do you write for a budget without cutting off the creative process?

AMY: There are ways to shoot big stuff so that it doesn't necessarily cost as much. If a car explodes in your script and you really want a car to explode and you don't have the money, you can go right to the edge with the car, swish pan around, see the person's face and make an explosion that impacts that person and throws them off their feet and then find the hulk of a car. If it's done well, you'll have the same effect as if you saw the car blow up.

There are ways to get around it and sometimes there are cleverer ways than blowing up a car. People have seen most things already, in special effects. Looking at somebody's reaction to what happened or looking at the aftermath of what happened or looking at it from a totally different point of view, there are a lot of different ways to see something. You don't have to eliminate it, you can imagine a different way to see it, too.

What’s your best piece of advice to someone starting a script?

AMY: Nobody does what I tell most people to do and that's to read a lot of scripts. That's the thing that has helped me the most in my career.

I remember when I first had to write a horror movie, when I first had to write a comedy, when I first had to write an action film, I would get myself down to the Writers Guild library or the Academy library and I would sit down and read some of the best of the genre.

If I was going to do a family drama, I would go read Terms of Endearment, or if I was going to go do a multiple character story, I'd read Syriana and Crash. Really read them. Instead, people go and look at the movie, and they think that did it. That doesn't do it. You have to read these scripts. You can study structure and see how really good people make it work.

No one would try to write a novel who hadn't read some novels. No one would try to write a play who hadn't read plays. But all the time people try to write screenplays who don't sit down and read them. The screenplay is a completely different form.

The vast majority of young writers you tell that to, the way they look at you, you know they're never going to do it.

Dying to make a feature? Learn from the pros!

"We never put out an actual textbook for the Corman School of Filmmaking, but if we did, it would be Fast, Cheap and Under Control."

Roger Corman, Producer

★★★★★

It’s like taking a Master Class in moviemaking…all in one book!

Jonathan Demme: The value of cameos

John Sayles: Writing to your resources

Peter Bogdanovich: Long, continuous takes

John Cassavetes: Re-Shoots

Steven Soderbergh: Rehearsals

George Romero: Casting

Kevin Smith: Skipping film school

Jon Favreau: Creating an emotional connection

Richard Linklater: Poverty breeds creativity

David Lynch: Kill your darlings

Ron Howard: Pre-production planning

John Carpenter: Going low-tech

Robert Rodriguez: Sound thinking

And more!

Write Your Screenplay with the Help of Top Screenwriters!

It’s like taking a Master Class in screenwriting … all in one book!

Discover the pitfalls of writing to fit a budget from screenwriters who have successfully navigated these waters already. Learn from their mistakes and improve your script with their expert advice.

"I wish I'd read this book before I made Re-Animator."

Stuart Gordon, Director, Re-Animator, Castle Freak, From Beyond

John Gaspard has directed half a dozen low-budget features, as well as written for TV, movies, novels and the stage.

The book covers (among other topics):

Academy-Award Winner Dan Futterman (“Capote”) on writing real stories

Tom DiCillio (“Living In Oblivion”) on turning a short into a feature

Kasi Lemmons (“Eve’s Bayou”) on writing for a different time period

George Romero (“Martin”) on writing horror on a budget

Rebecca Miller (“Personal Velocity”) on adapting short stories

Stuart Gordon (“Re-Animator”) on adaptations

Academy-Award Nominee Whit Stillman (“Metropolitan”) on cheap ways to make it look expensive

Miranda July (“Me and You and Everyone We Know”) on making your writing spontaneous

Alex Cox (“Repo Man”) on scaling the script to meet a budget

Joan Micklin Silver (“Hester Street”) on writing history on a budget

Bob Clark (“Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things”) on mixing humor and horror

Amy Holden Jones (“Love Letters”) on writing romance on a budget

Henry Jaglom (“Venice/Venice”) on mixing improvisation with scripting

L.M. Kit Carson (“Paris, Texas”) on re-writing while shooting

Academy-Award Winner Kenneth Lonergan (“You Can Count on Me”) on script editing

Roger Nygard (“Suckers”) on mixing genres

This is the book for anyone who’s serious about writing a screenplay that can get produced!