What was your filmmaking background before setting out to make "Not That Funny"?

Lauralee: I started producing other peoples' films, and made my first personal, handmade documentaries Laundry and Tosca and The Fair Trade (www.thefairtrademovie.com) less than a decade ago. With them I began to develop a style of storytelling that investigates the internal life of true stories. It intrigued me to go from there to making fiction by inserting narrative into documentary circumstances. I did that to a small degree with Not That Funny, and much more so now with my latest project Praying the Hours—with which I have much more creative license.

Not That Funny was a sort of commission I was hired to make, even though I did write, direct and in some ways help to produce it. It was a departure in some ways, but it was invaluable experience. I am influenced by Errol Morris, Terrence Malick, Kristof Kieslowski, Paul Thomas Anderson. Those will seem strange influences for a movie like Not That Funny, but it's all part of a long process of learning the craft and finding one's voice. I came to the process of directing later in my life, so I bring a lot of eclectic experiences with me.

Where did the idea come from and what was your process for working with your co-writer on the script?

Lauralee: The movie stars Tony Hale as a romantic lead, and this unique project started as a desire to show Tony's considerable range as a charismatic actor. We are friends and had been wanting to do a film for some time together. Then the executive producer of what became Not That Funny came to me with a low budget and a script that I didn't resonate with. I woke up soon after remembering a story idea that a friend of mine (cowriter Jonathan B. Foster) had—a story about a guy who tries to become funny to interest a woman he's taken with.

The idea of casting the funniest man I know as a serious romantic lead who tries to become funny and fails—that seemed like a great idea, and producer Jack Hafer went for it. I will always be grateful to him for letting us make the film we wanted to make instead of the script he had put a considerable amount of development time and money into finding. That was a bold risk. We brought in hands-on producer Terence Berry, and we were off.

As for the collaboration process, Jonathan lives in Seattle, and we flew him down to Los Angeles a couple of times, but mostly we wrote together through email and over the phone. I'd write at night after work, and he would write in the morning before work. We'd pass the drafts off to each other like relay runners. We have a very long and dear friendship, so we knew we would work well together, even though, as the saying goes, I hate writing—I like having written. But our collaboration could not have been more ideal. He's a gifted writer and a dear friend. Plus we did not kill each other.

Can you talk about how you raised your budget and your financial plan for recouping your costs?

Lauralee: This is the first film I have made that I am not financially responsible for, so I can't really answer that. As I say, the exec prod came to me with a set figure and the hopes that I could pull off a feature with it. We employed all the basic tenets of no-budget filmmaking, even though (in order to use Tony and most of our cast) we had to be a SAG signatory.

What camera did you use and what did you love and hate about it?

Lauralee: We bought two Canon 5Ds and borrowed a 7D as well. It was when the 5D was newly out and I think we were one of the first features shot with it. It was a risk back then because very few people were using the 5D for a product that was intended to hold up on a theater-sized screen. We ended up with an amazing look given the cost-point of the camera—I've seen it on large theater complex screens, and it looks amazing.

I started with the intention to have more than one camera and wanted the freedom of shooting in such a way that allowed everyone to keep their full-time jobs, so that meant having full access to the equipment. So, we purchased. Also, we scheduled over half the film with "micro-crews" in order to get authentic moments with a lot of ready-made production value by having a crew of 3-4 people (sometimes with a sound guy in a nearby van). In this case, the camera's low-profile SLR appearance allowed us to keep a relatively small footprint. We were very happy with how the film looked in the end.

Of course, there were challenges--it's a challenging camera to focus, it's not that mobile for hand-held, and it doesn't do very well with contrast, so we ended up with some blown out whites that we were unable to fix in post because there simply was no information there. We owe a great debt of gratitude to our DP Brandon Lippard, our editor Matt Barber, and our colorist Greg King for what they did with the limited resources we had. They made an amazing looking film.

Did the movie change much in the editing process, and if so, how?

Lauralee: As I say, our editor Matt Barber and our colorist Greg King were able to do wonders managing the great amount of footage we had and articulately cutting the film together, and then matching and enhancing that imagery. We all spent a lot of hours together, which was great because I came to love those guys very dearly. I was very lucky to work with this gifted team, and became very attached to them all, including Michelle Garuik who did miracles with the sound.

We shot and cut basically the film that we wrote, but I ought to acknowledge that we wrote the first draft alongside doing pre-production and wrote throughout shooting to accommodate shifting locations, cast hiccups, etc. I remember losing a location at the last minute and calling Jonathan at work in the middle of a company move to ask, "what will shift if we make Kevork an auto-repair guy instead of a shoe repair guy?" And he rewrote while we were driving to the new location.

And it should be said that the film matured in the editing process because of the music, as always. Our composer David Hlebo's soundtrack was augmented by some very talented local bands who are also friends—Evan Way, the Parson Red Heads, Lauren and Matt Meares, Jeana and Mikey Master, to name a few. The music has been a big hit with festival audiences, and we were privileged to have that kind of talent so generously loaned to us.

What was the smartest thing you did during production? The dumbest?

Lauralee: The smartest thing we did during production was to make the loving treatment of people our first priority. We have a code of honor that we call the Kinema Commonwealth, articulated by our First AD Matt Webb and editor Matt Barber, which calls for three things: the respectful treatment of the story, the creative artists involved (and by that I mean all the filmmaking community) and the community within which the film is shot. We had a reputation for creating a supportive environment, and Tony was a hero as the leading man setting the tone, he was always encouraging and in a great mood.

Conversely, he claims it is the best shooting environment he's ever been in. One of my favorite memories is from after we wrapped: one of the grips texted to say "I started a new show today and the director did not hug ANY OF US!"

We had great food hand-prepared by our Associate Producer Ron Allchin and his team (including his wife Dolores). The night that we wrapped one of the featured actors, he put his head on my shoulder and cried, saying he'd never in his life been treated so well by a film crew. I know the film industry has a reputation for eating its young, but from my perspective that's intolerable. Life is too short to treat people unkindly.

The dumbest thing we did was anything that failed at keeping that respect for people our first priority. I am not saying we always succeeded. But when we didn't, it was our biggest mistake.

And, finally, what did you learn from making the film that you have taken to other projects?

Lauralee: Not That Funny was a terrific experience for me, even though it was a departure from the style of film that I normally make. My creative partner at Burning Heart Productions Tamara Johnston McMahon and I made two sober, thoughtful documentaries before it and now we are working on a very ambitious project called Praying the Hours (www.prayingthehours.com) which is also much less light-hearted than Not That Funny.

But this film taught us a lot about the challenges of making a film that is sweet, humorous, charming. We wanted very much for it not to be a film that was broad humor, but one that left people feeling good and also thinking about what it means to truly love. We have had a great reception from audiences—we've won the audience award several times in festivals.

I am very proud of this little film, and what we were able to do with the resources we had available to us.

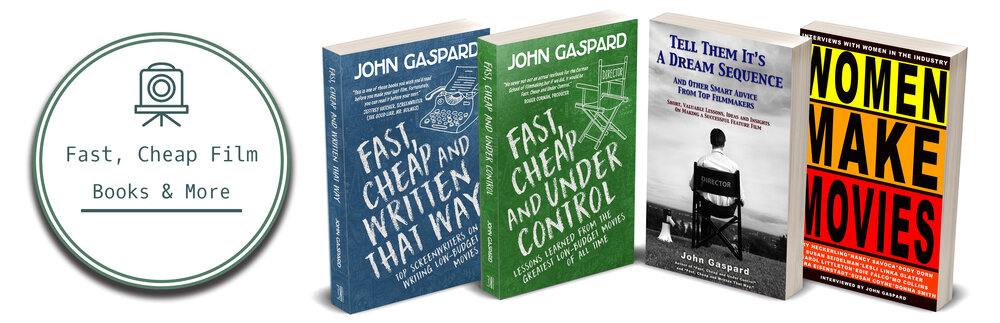

Dying to make a feature? Learn from the pros!

"We never put out an actual textbook for the Corman School of Filmmaking, but if we did, it would be Fast, Cheap and Under Control."

Roger Corman, Producer

★★★★★

It’s like taking a Master Class in moviemaking…all in one book!

Jonathan Demme: The value of cameos

John Sayles: Writing to your resources

Peter Bogdanovich: Long, continuous takes

John Cassavetes: Re-Shoots

Steven Soderbergh: Rehearsals

George Romero: Casting

Kevin Smith: Skipping film school

Jon Favreau: Creating an emotional connection

Richard Linklater: Poverty breeds creativity

David Lynch: Kill your darlings

Ron Howard: Pre-production planning

John Carpenter: Going low-tech

Robert Rodriguez: Sound thinking

And more!

Write Your Screenplay with the Help of Top Screenwriters!

It’s like taking a Master Class in screenwriting … all in one book!

Discover the pitfalls of writing to fit a budget from screenwriters who have successfully navigated these waters already. Learn from their mistakes and improve your script with their expert advice.

"I wish I'd read this book before I made Re-Animator."

Stuart Gordon, Director, Re-Animator, Castle Freak, From Beyond

John Gaspard has directed half a dozen low-budget features, as well as written for TV, movies, novels and the stage.

The book covers (among other topics):

Academy-Award Winner Dan Futterman (“Capote”) on writing real stories

Tom DiCillio (“Living In Oblivion”) on turning a short into a feature

Kasi Lemmons (“Eve’s Bayou”) on writing for a different time period

George Romero (“Martin”) on writing horror on a budget

Rebecca Miller (“Personal Velocity”) on adapting short stories

Stuart Gordon (“Re-Animator”) on adaptations

Academy-Award Nominee Whit Stillman (“Metropolitan”) on cheap ways to make it look expensive

Miranda July (“Me and You and Everyone We Know”) on making your writing spontaneous

Alex Cox (“Repo Man”) on scaling the script to meet a budget

Joan Micklin Silver (“Hester Street”) on writing history on a budget

Bob Clark (“Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things”) on mixing humor and horror

Amy Holden Jones (“Love Letters”) on writing romance on a budget

Henry Jaglom (“Venice/Venice”) on mixing improvisation with scripting

L.M. Kit Carson (“Paris, Texas”) on re-writing while shooting

Academy-Award Winner Kenneth Lonergan (“You Can Count on Me”) on script editing

Roger Nygard (“Suckers”) on mixing genres

This is the book for anyone who’s serious about writing a screenplay that can get produced!